Globally, no decoupling expected between GDP and energy consumption

To assess a country's carbon footprint, not only locally generated emissions are taken into account, but also those included in imported products. Otherwise, the relocation of part of a country's industrial activities outside its borders would give the illusion that it has reduced its carbon footprint. France's carbon footprint, for example, is 11tCO₂/capita, while emissions linked to domestic production alone are only 5 tCO₂/capita.

Jacques Treiner, University of Paris and Jacques Percebois, University of Montpellier

A similar approach should be taken to calculate the energy footprint of GDP, i.e., the amount of primary energy required to produce the goods and services consumed, also taking into account the energy used to manufacture imported goods and services. Here again, a reduction in a country's energy content will be illusory if, at the same time, it relocates its industrial activities and then repatriates the products it no longer manufactures.

While it seems logical that GDP growth should be accompanied by an increase in energy use, the correlation can become more complex in the long term, taking into account several factors: energy savings linked to improvements in energy-using equipment, substitution between forms of energy (some are more efficient than others), and changes in the structure of GDP (the shift toward services tends to reduce energy content, all other things being equal).

Let's try to gain a clearer understanding by starting from the concrete reality that we want to measure through these calculations.

GDP, energy, and material transformation

All goods and services are obtained through various transformations of matter, which can be analyzed physically to calculate energy balances and monetarily to contribute to GDP.

Energy consumption and GDP are therefore two ways of accounting for the same transformations of matter. Switching from one accounting method to the other is therefore analogous to a simple change of unit, which should result in a linear relationship between GDP and energy consumption—assuming that non-market activities represent only a small part of the production of goods and services. Do empirical data confirm this reasoning?

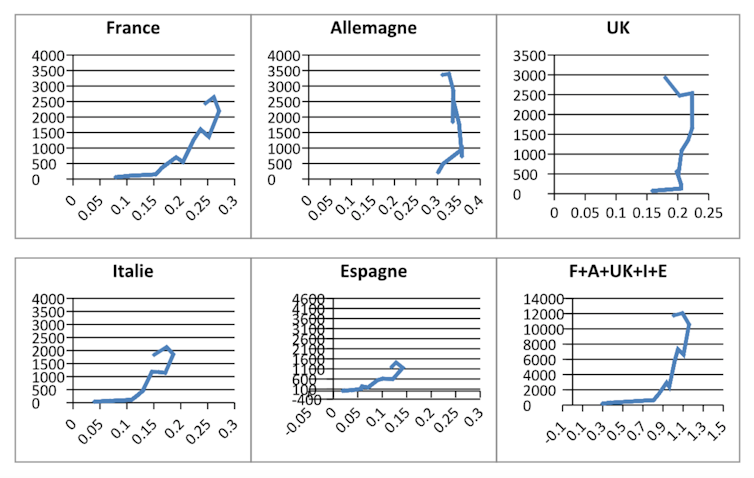

Let us first look at the national figures, which seem to contradict this assertion. The cases of Germany and the United Kingdom show that since the 1970s, there has been a fairly constant increase in energy-adjusted GDP, followed by an increase in GDP associated with a decrease in energy consumption.

Our World in Data

Striking contrasts between Europe and Asia

When these five representative European countries are aggregated, three patterns emerge, characterized by different slopes in the GDP/energy ratio: the first before the oil shocks of the 1970s; the second, marked by a sharp break in the slope, undoubtedly associated with a significant improvement in energy efficiency; and in recent years, a third regime marked by GDP growth combined with a decrease in primary energy consumption.

Part of this change can be explained by a shift in the structure of GDP, but also by improvements in energy efficiency. The explanatory variable is, of course, the price of energy: oil shocks have made energy more expensive, leading to greater efficiency and substitutions between forms of energy.

More recently, the introduction of a carbon price in industrialized countries may explain the efforts made to reduce the unit consumption of products. However, this measure also encourages carbon leakage, which amounts to relocating polluting industries.

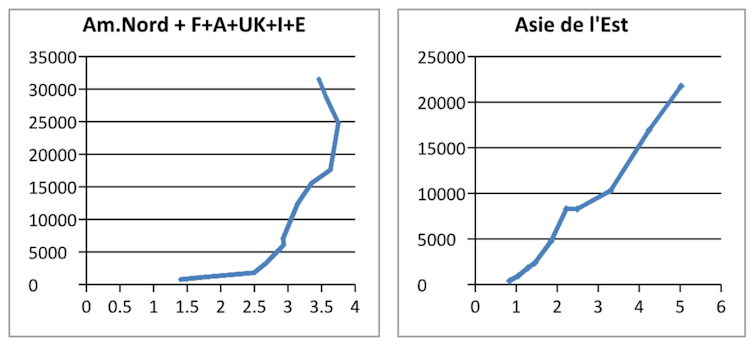

These three trends are confirmed when data for North America is added. An initial change in slope in 1975, caused by the first oil crisis, and the onset of a "strong decoupling" in wealthy countries in the early 2000s: GDP growing with less energy.

Our World in Data

The contrast is striking with East Asia, where a trend can be observed that seems to confirm the initial proposition of a linear relationship between GDP and energy consumption.

As for the regions of the world not represented here—South Asia, Latin America, Africa—they are following the same trend as East Asia, with a lag of a few decades.

However, these countries are characterized by a growing importance of industrial activities—this is particularly the case in China.

A decoupling that is more apparent than real

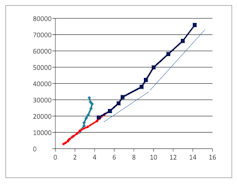

Let us now aggregate all the global data. We then identify two patterns, with a slight improvement in energy efficiency beginning in the late 1990s, but no "strong decoupling."

Given that this trend is occurring at a time when China is entering the global market on a massive scale, the following interpretation can be proposed: in order to analyze the relationship between GDP and energy, it is necessary to consider economically autonomous entities or to take international trade into account. Only under these conditions can the same transformations of matter be accounted for, both in the calculation of their energy consumption and in their contributions to GDP.

Since the 2000s, many activities that are essential to the functioning of societies and very energy-intensive have been relocated, particularly to China. The "decoupling" in rich countries is more apparent than real; it is mainly the result of their "partial deindustrialization."

A linear relationship between GDP and energy consumption appears to be well confirmed by global aggregate data, with a slightly increasing slope, corresponding to a long-term improvement in energy efficiency.

World Bank

Globally, economic growth will therefore continue to be accompanied by an increase in energy consumption, at varying rates depending on the period.

At the regional level, and even more so at the national level, the situation will be different. Economic growth will involve lower energy consumption, thanks to technical improvements and structural changes in GDP.

However, the energy saved in some countries will be used in others on behalf of the former. The sharp drop in final energy consumption expected in France between now and 2030 according to the PPE, which should be accompanied by a significant reduction inCO2 emissions, may therefore mask delocalized consumption and emissions.

To refine our understanding of the energy impact linked to a country's GDP, it therefore seems essential to also take into account the energy content of its imports, in a context of globalized national economies.![]()

Jacques Treiner, Theoretical physicist, associate researcher at the LIED-PIERI laboratory, University of Paris and Jacques Percebois, Professor Emeritus at the University of Montpellier, researcher at the CNRS Art-Dev joint research unit, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.