Teaching robots to improvise (with tools)

Humans are very good at using tools in unexpected ways. Don't have a spoon? You'll use a pen to stir your coffee. Need a bolt to hang a lamp? A rubber band will do the trick for now. Need a tray? A book or tablet will do. This ability to improvise does not come out of nowhere; it is the result of cognitive abilities that allow us to make connections between objects, the tools at our disposal, and their uses.

Ganesh Gowrishankar, University of Montpellier

The use of tools in robots has so far been considered a problem of exploration and learning: a robot needs to discover how a tool can be used, either by trying out various strategies or by observing and imitating other humans or robots. In our study published in Nature Machine Intelligence, we showed that robots can be taught to think more creatively, or "outside the box," as English speakers would say.

To enable robots to use tools intuitively like humans, we first examined how we humans are able to do so.

Towards "tool cognition" in robots

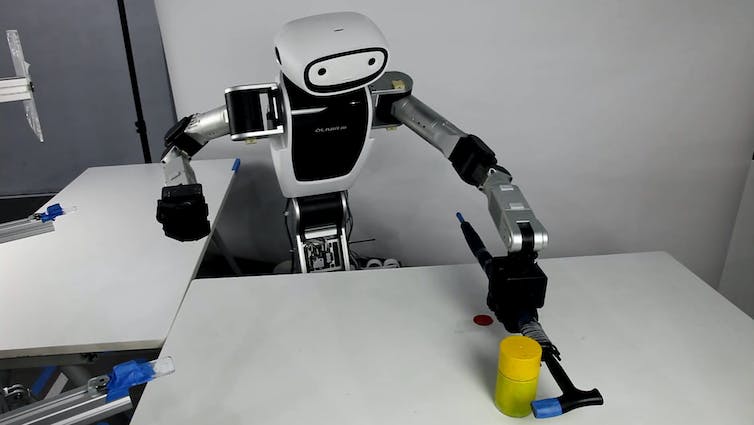

A robot needs to pick up a bucket, but the path is blocked by some obstacles. This robot cannot move the obstacles or jump over them. But it was able to search for—and find—a cleaning stick and use it as a tool to pick up the bucket.

This simple use of a tool may seem obvious to a human, but it is a complex challenge for a robot.

In fact, using tools first requires the robot to understand that it cannot perform a task without a tool (1). It must then find an object in its environment that it can use as a tool to perform the requested task (2). To do this, it must figure out how to use this tool, i.e., determine the actions to be performed (3). And finally, of course, it must perform these actions... and thus complete the task (4).

The second and third challenges are fundamental cognitive challenges, which humans seem to be very good at... and robots, significantly less so.

Our new algorithm for "tool cognition" in robots is a major step forward in addressing these challenges.

How do humans recognize that an object is suitable for use as a tool for a given task?

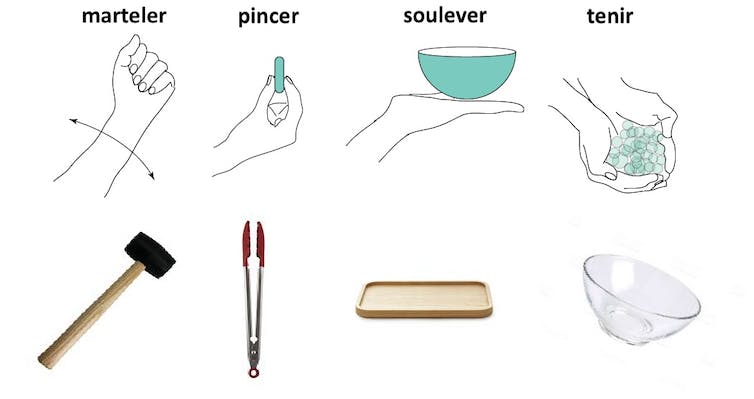

In our work, we categorized tools based on how we, as humans, use them. This categorization shows that humans can actually only intuitively recognize a very specific category of tools.

These "category 1" tools are tools that enable us to perform tasks that are already within the human repertoire. For example, pliers help us to grasp objects, but we can already do this with our fingers; a hammer helps us to strike objects, which we can already do with our fists.

Using these "category 1" tools requires the same action as you would perform without a tool: pliers need you to pinch, which is similar to what you would do with your fingers; a hammer requires you to make oscillating striking movements, and you would make the same movement without a hammer.

Category 1 tools are probably the most common in human and animal life. The first tools used by humans, stones for striking and breaking fruit and cutting it, were Category 1 tools, because humans could perform these tasks, with similar actions, using their fists and nails respectively. And in fact, the tools used by animals can be classified as Category 1.

We refer to tools that enable tasks to be performed that humans can perform without tools but with very different movements (such as a car jack to lift a car) as "category 2" tools.

Category 3 tools enable tasks to be performed that are beyond human capability (such as a vacuum cleaner or a chainsaw).

These category 2 and 3 tools cannot be used intuitively by humans: you have to read instructions, imitate another user, or explore the tool to figure out how to use it.

Tools that humans use intuitively

It is believed in psychology that one of the reasons humans are good at using tools is that tool use leads to a "embodiment" of tools, meaning that the brain eventually considers tools to be an "extension" of our bodies.

In our work on the "embodiment" of tools and limbs by humans, we have observed that the similarity between an object's characteristics and the functional characteristics of a limb is important for its embodiment.

This observation, along with our characterization of tools, suggests that humans may use their limbs as a reference point for identifying Category 1 tools: a hammer is recognized as a tool for striking objects because it closely resembles a fist and an arm, a pair of pliers is recognized as a tool for pinching because it resembles fingers, and similarly, a plate resembles a palm and a bowl resembles cupped hands. By identifying and comparing the posture of our limbs when performing a task, we can identify tools that can be used for the task performed with the same posture.

Using similarity with its members is the key idea used to program our robot.

Teaching robots to recognize tools that resemble what they know

Our algorithm uses this idea to enable robots to recognize objects (even those they are seeing for the first time) as tools for each task they are capable of performing "without tools" (i.e., using their limbs, without any additional objects).

Once a robot has learned to perform a task with its limbs, our algorithm allows it to use its limbs as a reference to recognize the tools that help it perform the same task. Furthermore, by definition, since category 1 tools require the same action as without tools, the robot can use the same skill ("controller") to use the tool by simply increasing its body kinematics according to the new tool.

The robot does not need to have used a single tool before, nor even to have observed others using tools.

In our proposal, we also provide a grasping planning algorithm for picking up and using the identified tools. Unlike the algorithms previously described in the scientific literature, ours is the first to enable robots to use tools without having to learn beforehand with the same tools or with other tools.

However, for the moment, our algorithm only allows robots to use category 1 tools, i.e., tools for tasks that the robot is capable of performing without tools. For category 2 and 3 tools, learning or observation (followed by imitation) is necessary, as with previous tool-use algorithms.

Furthermore, the algorithm can be extended to the use of tools similar to those already known to the robot: basically, "similarity to a member" is replaced by "similarity to a known tool," as suggested by the algorithms described above.

However, as we have seen, Category 1 tools appear to be the most basic tools used by humans and animals, and we therefore believe that our algorithm represents a significant step toward tool cognition in robots.

Ganesh Gowrishankar, Researcher at the Montpellier Laboratory of Computer Science, Robotics, and Microelectronics, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.