Before the asteroid strike that caused their extinction, dinosaur species were already in decline.

Sixty-six million years ago, an asteroid approximately 12 kilometers in diameter crashed into Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula. The impact caused an explosion of unimaginable magnitude: several billion times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Most of the animals on the American continent were killed instantly.

Fabien Condamine, University of Montpellier

The impact also triggers global tsunamis. In addition, tons and tons of dust are ejected into the atmosphere, plunging the planet into darkness. This "nuclear winter" therefore sees the extinction of a very large number of plant and animal species. Among the most iconic of these are the dinosaurs. But before this cataclysm, how was this group faring? This is the question we sought to answer in our study, the results of which have just been published in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

We focused on six families of dinosaurs, the most representative and diverse of the Cretaceous period, particularly the last 40 million years. Three were carnivores: Tyrannosauridae, Dromaeosauridae (including the famous velociraptors, made famous by the Jurassic Park films) and Troodontidae (small dinosaurs closely related to birds). The other three families we studied were herbivores: the Ceratopsidae (represented in particular by the Triceratops), the Hadrosauridae (the most diverse of all the families) and the Ankylosauridae (represented in particular by the ankylosaurus, a kind of "tank" with bone armor and a club-like tail).

Mariana Ruiz Villarreal LadyofHats/Wikimedia, CC BY

Our goal was to determine how quickly these families diversified (species formation) or became extinct (species extinction). We knew that all of these families had survived until the end of the Cretaceous period, marked by the asteroid impact.

1,600 fossils analyzed

For five years, we compiled all known information on these families in an attempt to determine how many and which species each group contained. The work was tedious, as we cataloged most of the known fossils for these six families, representing more than 1,600 individuals for approximately 250 species. Several difficulties arise for each fossil: correctly categorizing the species and dating it accurately.

Fortunately, this work was carried out with eminent paleontologists (Guillaume Guinot, Mike Benton, and Phil Currie). In the scientific community, for traceability purposes, each fossil is given a unique number, which allows us to track it in scientific literature over time. It was painstaking work, because one author might assign a date and species to a fossil, then another would re-examine it and make a different analysis, and so on. So we had to make decisions. If we had too many doubts, we would eliminate the fossil from the study.

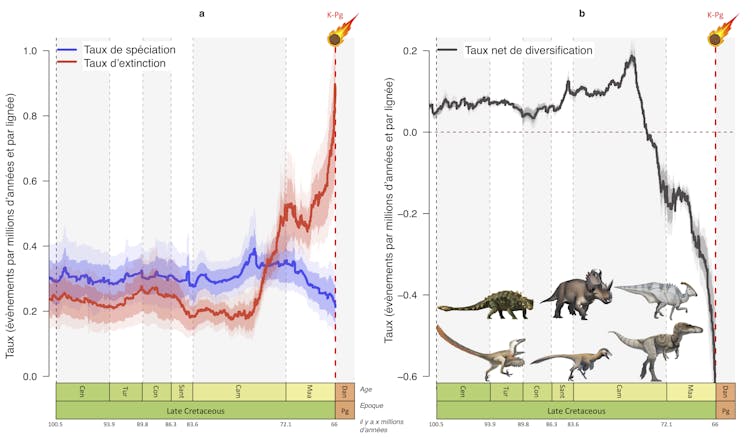

Once each fossil had been properly categorized, we used a statistical model to estimate the number of species over time for each family. We were therefore able to trace the species that appeared and disappeared over millions of years (from 160 to 66 million years ago) and estimate, again for each family, the rates of speciation and extinction over time.

Fabien Contamine, Provided by the author

To estimate speciation and extinction rates, several biases had to be taken into account. The fossil record is indeed biased. It is uneven in time and space, and some groups do not fossilize well. This is a well-known problem in paleontology when attempting to estimate the dynamics of past diversity. Given these problems, modern, sophisticated models can take into account the heterogeneity of preservation over time and between species. In doing so, the fossil record becomes more reliable for estimating the number of species at a given time. But it is important to remain cautious, as we are talking about estimates, and these estimates may change with a more complete fossil record, for example, or with new analytical models.

The decline of herbivores preceded that of carnivores.

In this study, our results show that, 10 million years before the asteroid strike, starting at 76 million years ago, the number of dinosaur species was in sharp decline. This decline is particularly interesting because it was global and affected both carnivorous groups such as tyrannosaurs and herbivorous groups such as triceratops. It also occurred in the Old World (Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia) and the New World (the Americas). There is still some heterogeneity in the response. Some declined sharply, such as ankylosaurs and ceratopsians, and only one family (troodontids) out of six shows a very slight decline, which occurred in the last 5 million years.

What could have caused this sharp decline? At that time, the Earth underwent a global cooling of 7 to 8°C.

We know that dinosaurs needed a warm climate for their metabolism. As we often hear, they were not ectothermic (cold-blooded) animals like crocodiles or lizards. Nor were they endothermic (warm-blooded), like mammals or birds. They were mesothermic, a system between reptiles and mammals, and needed a warm climate to maintain their temperature and thus perform basic biological functions such as metabolic activities. This decline must therefore have had a very strong impact on them.

It should be noted that we found a staggered decline between herbivores and carnivores. Grass eaters declined slightly before meat eaters. The decline of herbivores appears to have caused that of carnivores. So, according to our model, as soon as herbivores become extinct, carnivores disappear, which is known as a cascade of extinctions. Herbivores are key species in ecosystems (even today in the savannas of Africa, for example). Many species "gravitate" around herbivorous species. Their extinction often leads to the extinction of other species that depend on these herbivores.

The big question that remains unanswered is: what would have happened if the asteroid hadn't crashed? Would the dinosaurs have become extinct anyway, due to their already declining numbers, or could they have bounced back? It's very difficult to say. Many believe that if they had survived, primates and therefore humans would never have appeared on Earth. An important fact is that a possible rebound in diversity can be very heterogeneous and depend on the group, so that some groups would have survived and others would not. Hadrosaurs, for example, show a certain resilience to decline and could perhaps have rediversified after the decline.

In any case, it could be said that ecosystems at the end of the Cretaceous period were under pressure (climate deterioration, major changes in vegetation), and that the asteroid was the final blow. This is often the case with species extinction: they are first in decline, under pressure, and then another event occurs and finishes off a group that may have been on the brink of extinction before that event.![]()

Fabien Condamine, CNRS Researcher in Phylogeny and Molecular Evolution, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.