Airplanes: who is willing to pay more to pollute less?

The growth prospects for the aviation sector are undermining its technological efforts to reduce carbon emissions. These costly initiatives will have to be passed on to ticket prices in order to be implemented. But are passengers willing to pay more for greener flights? A survey of 1,150 people in 18 countries provides some answers.

Sara Laurent, Montpellier Business School; Anne-Sophie Fernandez, University of Montpellier; Audrey Rouyre, Montpellier Business School and Paul Chiambaretto, Montpellier Business School

Although air transport accounts for only a limited share of CO₂ emissions (2.1%) and greenhouse gas emissions (3.5%), the sector faces a complex situation.

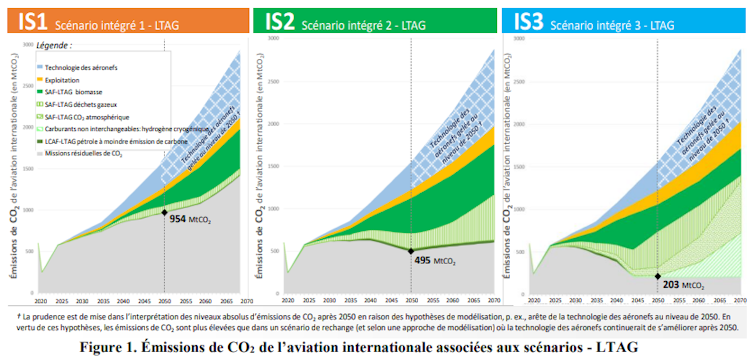

On the one hand, over the past few decades it has developed numerous technological innovations that enable it to reduce kerosene consumption and, as a result, CO₂ emissions per passenger carried. On the other hand, air traffic growth has never been as strong as in recent years—apart from the Covid-19 hiatus. Forecasts seem to confirm this trend for the next 20 years, particularly in developing countries, which negates all the efforts made by the aviation industry.

Faced with this challenge, the aviation industry is pursuing more radical innovations, from more sustainable aviation fuels to electric aircraft. But these "green" innovations are complex and costly to develop and adopt by airlines.

An additional cost that airlines will be tempted to absorb by passing it on to the price of airline tickets, which could directly affect passengers' wallets. But are passengers really willing to pay more to travel greener? We tried to answer this question through an experiment conducted in 18 countries across Europe, North America, Asia, and Oceania, surveying 1,150 people to better understand how they choose their airline tickets.

Nearly 10 cents more for 1 kg less CO₂

We offered them flights with different options: price, comfort, baggage allowance, duration, etc., but also based on the type of fuel used andCO2 emissions. The goal? To find out if they were willing to pay a little more for less polluting aircraft.

Various innovations, with varying degrees of environmental impact, were proposed. For each of them, without ever explicitly asking respondents, we were able to calculate their willingness to pay, i.e., the additional amount they are willing to pay to reduce theirCO2 emissions.

The survey mainly showed that passengers are willing to pay an average of 10 euro cents to reduce their emissions by 1 kg ofCO2. In other words, for a domestic flight (within France) that will emit 80 kg ofCO2, our passengers would be willing to pay an average of €8 more to avoid polluting at all.

However, these amounts remain modest compared to the actual additional costs associated with adopting these innovations. For example, sustainable aviation fuels cost four to six times more than kerosene, meaning that the additional cost to the airline would be much higher than the extra €8 that our passengers would be willing to pay.

Those who feel guilty are willing to pay more

However, not all air passengers are willing to pay the same amount, and some would accept much more than 10 cents per kilogram. Who are those who accept?

Contrary to popular belief, young people (who generally claim to have stronger environmental values) are not inclined to pay more than the rest of the population, and people with higher levels of education are not more sensitive to this issue.

Certain psychological variables, however, seem to play a much more important role. Passengers who feel a strong sense of shame at the idea of flying (flight shame) – around 13% of respondents – say they are willing to pay between 4 and 5 times more than those who do not feel this way (27 cents/kg, compared to 6 cents/kg of CO₂).

Similarly, people with strong environmental values or who adopt eco-friendly behavior in their daily lives tend to be more willing to pay (between 17 and 34 cents to reduce their CO₂ emissions by one kilogram).

Similarly, in terms of behavior, frequent flyers and business travelers consider that they could pay around 15% more than other travelers to reduce CO₂ emissions associated with their flights.

Airlines should therefore adopt a more targeted approach by focusing primarily on air passengers who are motivated by their values or behaviors to make an effort.

The need to provide better information on innovations

Beyond these figures, our study invites strategic reflection among air transport stakeholders. Airlines cannot rely solely on consumer goodwill to finance their ecological transition. While passengers are generally in favor of greener aviation, their willingness to pay remains below actual financing needs.

Two levers are therefore essential: education and incentives.

- From an educational perspective, it is crucial to communicate more effectively about the concrete environmental benefits of SAF (Sustainable Aviation Fuels) and other disruptive technologies. Better communication could familiarize the general public with these innovations and thus increase their confidence in the sector, and even their willingness to pay more. To achieve this, targeted and educational marketing campaigns could be implemented. While avoiding greenwashing, these campaigns must be rooted in a logic of education and transparency.

- In terms of incentives, introducing attractive pricing for low-impact flights or rewarding eco-friendly behavior in airline loyalty programs could help convince some of the more reluctant members of the public, encouraging them to adopt more virtuous behavior for reasons other than those related to the environment.

The inevitable reduction in air traffic

So, should we pay more to pollute less? Our findings show that travelers are willing to make an effort, but not to the extent required by the enormous demands of the transition. Sustainable aviation cannot therefore rely solely on the goodwill of passengers: it will require collective action, with airlines, public authorities, manufacturers, and travelers all working together.

Indeed, SAF consumption is limited by current supply capacities to meet the needs of all industrial sectors, particularly road transport. The use of new forms of energy by the aviation industry is therefore only part of the solution for medium- and long-term action. Reducing traffic and taking action on demand are inevitable steps toward lowering CO₂ emissions from aviation.

It is up to airlines to play the transparency card in order to build trust and influence behavior. It is up to passengers and public decision-makers to shoulder their share of the cost of greener skies. Because the question that looms large is not only how much a plane ticket will cost tomorrow, but who, collectively, will be able to invent a sustainable model for flying.

Article published in collaboration with other researchers from the Pégase Chair (MBS School of Business) at the University of Montpellier and Bauhaus Luftfahrt – Ulrike Schmalz, Camille Bildstein, and Mengying Fu.

Sara Laurent, Assistant Professor of Marketing, Montpellier Business School; Anne-Sophie Fernandez, University Professor, University of Montpellier; Audrey Rouyre, Lecturer and Researcher in Strategic Management, Montpellier Business School, Montpellier Business School and Paul Chiambaretto, Professor and Director of the Pégase Chair, Montpellier Business School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.