Well-being at work: what if SCOPs had it all figured out?

Claude Fabre, University of Montpellier and Florence Loose, University of Montpellier

The 2023 pension reform, which confirms the postponement of the legal retirement age to 64, raises the question of the sustainability of work. According to Dares, the statistical department of the Ministry of Labor, 37% of employees did not feel capable, in 2019, of continuing in their jobs until retirement. Exposure to occupational risks—both physical and psychosocial —is one of the main reasons for this high figure.

The recruitment difficulties and various forms of resignation (visible or silent) experienced by many companies can be explained in part by the working conditions perceived in the sector or in the position offered, and, more generally, by the gap between the expectations of some and the offers of others. Two years of the Covid crisis have profoundly changed the situation. It is therefore no surprise that specialists now consider Quality of Life and Working Conditions (QLWC) to be a key factor in a company's attractiveness, retention and performance.

Faced with this situation, the authors of the Dares study conclude:

"A work organization that promotesautonomy and employee participation and limits work intensity tends to make work more sustainable."

Exposure to risks, whether physical or psychosocial, goes hand in hand with an increased sense of unsustainability. Autonomy and social support (from superiors, colleagues, or employee representatives) promote sustainability, just as participation in decision-making mitigates the impact of organizational changes.

This type of organization is found in cooperative and participatory companies (SCOP). These are corporations (SA) or limited liability companies (SARL) that have become " social and solidarity economy enterprises" (ESS) by choice and by approval. The principles (goals other than profit, dual human and economic objectives) and rules of the SSE (governance, profit sharing) are thus enshrined in their articles of association.

In these structures, employees are the majority shareholders: they hold at least 51% of the share capital and 65% of the voting rights. Power is exercised democratically and profits, risks, and skills are shared. SCOPs thus differ from traditional companies in terms of their objectives and guiding principles, the status of partner open to their employees, and their decision-making, organizational, and remuneration practices. Quality of life and well-being at work are at the heart of the project and are not secondary or optional issues.

Following two surveys conducted among 205 managers and 554 employees (in a research project in partnership with the General Confederation of SCOPs, CGSCOP), we were able to observe a high level of involvement and commitment at work, as well as a general sense of well-being.

Effective power

Both managers and cooperative members report high levels of well-being on average. The table below summarizes our respondents' self-assessments (score out of 10):

This well-being is promoted by cooperative practices (work organization, decision-making, remuneration) that influence employee involvement, commitment, and sense of security. It also impacts the company's economic performance.

Employees particularly appreciate their decision-making power. The feeling of empowerment, i.e., emancipation, is particularly high (8.32/10). According to American researcher Gretchen M. Spreitzer, this is what employees experience when they exercise effective power over their professional environment, through a sense of competence, impact on what is happening in their company, autonomy in decisions concerning their work, and meaning they find in their work.

[More than 85,000 readers trust The Conversation's newsletters to help them better understand the world's major issues. Subscribe today]

Thus, even though not all cooperative members exercise their right to speak in the same way and participation varies in practice, these companies are characterized by a fairly high level of member participation in strategic and operational decision-making.

For cooperative members, this decision-making power gives them a sense of genuine involvement in their organization. The table below shows employees' self-assessments of different levels of involvement:

Finally, it should be noted that employee-owners have higher levels of emotional involvement, normative involvement,empowerment (through feelings of competence, autonomy, and impact), and job security than non-employee-owners.

Psychological contract

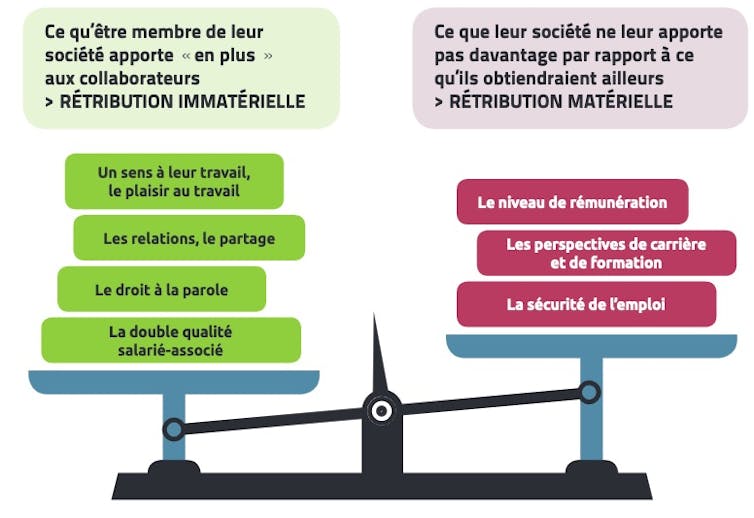

Overall, our respondents believe that the psychological contract with their company is unique and specific to this type of structure. Indeed, the contract between an employee and a company is not only legal: it is also moral. What I can give (my contributions) and what I can receive (remuneration) goes beyond the employment contract. For example, I give my loyalty in exchange for quality of life at work. It is a "deal" that employee-partners consider to be balanced.

Our study reveals the importance of cooperative values (support, sharing, democratic participation, right to speak, etc.) in the psychological contract within SCOPs. These "intangible" aspects of the contract compensate for more tangible aspects (remuneration, training, career development, etc.) in which SCOPs do not outperform traditional companies.

Indeed, cooperative members believe that their "intangible" contract is all the more valuable because it would be very difficult to find elsewhere, in traditional organizations. In addition, this intangible component of the contract makes it possible to predict key variables such as the well-being of cooperative members and the high value they place on their work.

The need for "transformational" leadership

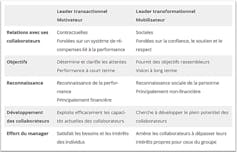

However, for everyone, managers and cooperative members alike, the level of well-being depends on the leadership style. Even if employees are partners and the term "manager" or "advisor" is often preferred to "leader" or "manager," the presence of a leader to bring the cooperative model to life remains necessary.

Surveys conducted reveal the importance of the leadership style adopted within these companies. The so-called "transformational" style (which encourages autonomy, recognition, and appreciation of each member) is perfectly in line with the values and functioning of SCOPs. Such a leader therefore has a very positive influence on the well-being at work of all members, including his or her own. On the other hand, if their style is more "transactional," their professional behavior appears ill-suited to cooperative functioning and incompatible with the aspirations of the cooperative members: this style does not promote their own well-being or that of others.

These results highlight a virtuous circle, characterized not by highly innovative mechanisms, as we might imagine, but by clusters of organizational and managerial practices that are both rewarding for employees and economically efficient, guided by values and objectives that are firmly anchored in the statutes and non-negotiable. While not without its weaknesses or exempt from the constraints faced by any business, one of the successes of SCOPs in the current context is their ability to combine the collective (community spirit and solidarity) with the individual (autonomy, responsibility, development), the human and the economic. Yes, it is possible!

According to the SCOP network, at the end of 2022, there were 2,606 such structures, present in all sectors of activity, accounting for 58,137 jobs and $8.4 billion in turnover. These cooperative enterprises also recorded 11% growth compared to 2021. The five-year survival rate increased by 3 points compared to 2021, reaching 76% compared to 61% for French companies as a whole. The strength of SCOPs therefore remains a serious asset for the French economy in terms of employment policies, but also in terms of policies aimed at promoting well-being at work.

Claude Fabre, Associate Professor of Management Sciences (specializing in human resources), University of Montpellier and Florence Loose, Associate Professor of Social Psychology, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.