What the Teil earthquake teaches us about seismic risk in mainland France

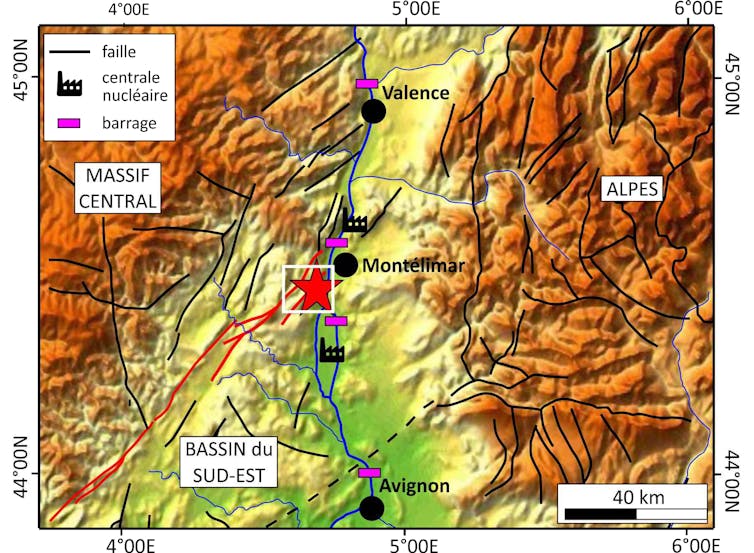

One year ago, on November 11, 2019, at 11:52 a.m., the Montélimar region was severely shaken by a 5.4 magnitude earthquake.

Christophe Larroque, University of Reims Champagne-Ardenne (URCA); Jean-Francois Ritz, University of Montpellier; Laurence Audin, Institute of Research for Development (IRD); Matthieu Ferry, University of Montpellier and Stéphane Baize, Institute for Radiological Protection and Nuclear Safety (IRSN)

With more than 700 buildings seriously damaged and four people injured, this earthquake, which was felt throughout southeastern France, is the most destructive in mainland France since the onein Arette in the Pyrenees in 1967. This region, on the edge of the Rhône Valley, is particularly vulnerable due to the presence of several urban areas and large industrial facilities: dams, nuclear power plants, roads, railways, and rivers.

This earthquake prompts us to reassess seismic risk in mainland France: on the one hand, we must now take into account this type of very shallow earthquake, capable of producing strong ground movements; and on the other hand, we must factor in the possibility of surface rupture, i.e., a permanent break in the ground, which poses a particular danger to sensitive facilities.

A shallow earthquake and a very clear ground shift

A few dozen minutes after the earthquake, it was known that the epicenter was located near the village of Le Teil, with a very shallow focus (the area where the rupture began at depth), between one and three kilometers below the ground, which explains the high intensity of the ground movements and, consequently, the extent of the destruction. In fact, the seismic waves produced at the focus traveled a short distance before reaching the surface, and their energy was only slightly attenuated.

Christophe Larroque, Author provided

In the afternoon, the first teams of seismologists set out to install sensors in the field to record aftershocks—smaller tremors that systematically follow a major earthquake. The next day, satellite radar images and their analysis using "radar interferometry" revealed vertical shifts in the ground surface exceeding ten centimeters.

For geologists, two observations emerged: on the one hand, the epicenter of the earthquake was very shallow; on the other hand, the areas of vertical ground displacement seen in the radar images were aligned in an almost straight line. These observations are very important because they suggest that the part of the fault that ruptured during the earthquake (known as a "cosismic" rupture) reached the surface, which is a very rare event for an earthquake of this magnitude. So rare that, at the time of the Teil earthquake, no indisputable cosismic rupture on the ground surface had ever been described in mainland France.

The formation of a "step" on the surface

The vertical shifts detected by radar interferometry are aligned along a northeast/southwest direction corresponding to an older fault, the Rouvière fault. Analysis of these shifts indicates uplift of the southern compartment. On November 13, a team from several French laboratories set out to search for potential surface ruptures. Despite the difficulties on the ground, due to vegetation and rugged terrain, several signs of ground surface rupture were discovered, some showing vertical offsets of between 2.5 and 15 centimeters.

Philippe Desmazes/AFP

These measurements also show that the southern section of the fault has risen, and their distribution confirms that they are indeed the result of the arrival at the surface of the co-seismic rupture associated with the earthquake.

An ancient fault... but still active

These observations are unprecedented. This is the first time that such a "cosismic" rupture—the rupture of the fault during the earthquake—has been observed on the surface and "live" in France. Very few cases have been reported worldwide for earthquakes with a magnitude of less than 5.5.

The Rouvière fault, where the Teil earthquake occurred, is an ancient fault that was not mapped as active, i.e., capable of producing such an event.

R. Lacassin/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

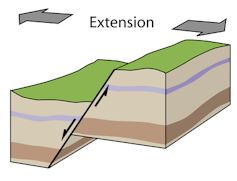

It is about ten kilometers long and forms one of the northern segments of the large Cévennes fault system, which stretches over more than 120 km between Lodève and Valence. The last significant movements on the Rouvière fault date back to the Oligocene period, between 35 and 25 million years ago. During the Oligocene, this fault functioned as a "normal" fault in an extensional tectonic regime, contemporary with the opening of the western Mediterranean Sea. The movements along the fault then caused the Rhône valley to subside relative to the Ardèche border.

The movements of the Rouvière fault have reversed

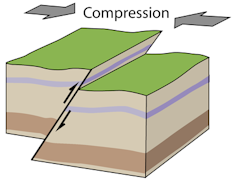

However, during the Teil earthquake, the southern compartment rose. The 2019 earthquake therefore indicates that movement along the Rouvière fault has reversed.

RobinL/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

Fault reversal is a known process in the evolution of large geological structures. In this case, the Rouvière fault operated in a "normal" direction in ancient times, meaning that the block located south of the fault descended relative to the block located north of it. Recently, however, its direction of slip has reversed, and the southern block is now rising along the fault plane relative to the northern block.

The Teil earthquake is particularly interesting from this point of view, as it illustrates "live" the reversal of a normal fault, and consequently the change in tectonic regime.

Since the 1960s, it was thought that earthquakes in the region could be explained quite simply by the convergence between the African and European plates, which generates forces towards the north from the boundary between these plates located south of the Mediterranean. However, observations and modeling carried out over the past twenty years have called this single mechanism into question: it appears that local processes, such as erosion, the melting of large Alpine glaciers 15,000 years ago, and the circulation of fluids in the Earth's crust, are also capable of producing earthquakes.

Human activities on the Earth's surface are also discussed as potential triggers for earthquakes. In the case of Le Teil, the extraction of a large mass of rock from a quarry located above the fault may have caused the event.

In short, the origin of the forces producing "intraplate" earthquakes in Western Europe is not yet clearly understood and is the subject of much research.

See also:

Earthquake in the Aegean Sea: what do scientists know after several days of work?

Exploring the past to better understand the present and the future

Paleoseismologists decipher past earthquakes. In this case, they are studying the Rouvière fault and other faults that make up this part of the Cévennes fault network in order to determine whether they have already produced surface ruptures over the last 2 million years. They analyze whether deformations associated with earthquakes (e.g., cracks, ruptures with displacement, folds, tilts) affect the most recent sedimentary layers (such as slope debris, fluvial alluvium, sand) at the level of trenches they dig across the faults.

Christophe Larroque, Author provided

They seek to determine the ages and movements produced by these deformations in order to estimate the frequency and magnitude of ancient earthquakes. By assuming that the current behavior of a fault is similar to its past behavior (the principle of "actualism"), paleoseismological data can be used to discuss the probability of a fault producing an earthquake over a certain period of time.

Let us hope that the work currently underway in the Teil region will provide sufficient data to enable this seismic risk assessment to be carried out on this part of the Cévennes fault system.![]()

Christophe Larroque, Associate Professor, University of Reims Champagne-Ardenne (URCA); Jean-Francois Ritz, Director of Research , University of Montpellier; Laurence Audin, Director of Earth Research , Research Institute for Development (IRD); Matthieu Ferry, Senior Lecturer in Geomorphology, University of Montpellier and Stéphane Baize, Researcher in Earthquake Geology, Institute for Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety (IRSN)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.