These metals are running out, posing a challenge for tomorrow's societies

Many metals are essential for21st-century technologies, particularly many "green" technologies, such as batteries, solar panels,wind turbine magnets, and fiber optics. Some of these metals are considered "critical" because their supply is uncertain.

Alexandre Cugerone, University of Montpellier; Bénédicte Cenki-Tok, University of Montpellier and Emilien OLIOT, University of Montpellier

We seek to understand how certain critical metals concentrate in the Earth's crust in order to extract them more easily, with a view to inspiring new methods of exploration and environmentally responsible recovery of certain waste products from past mining operations, particularly in France and Europe.

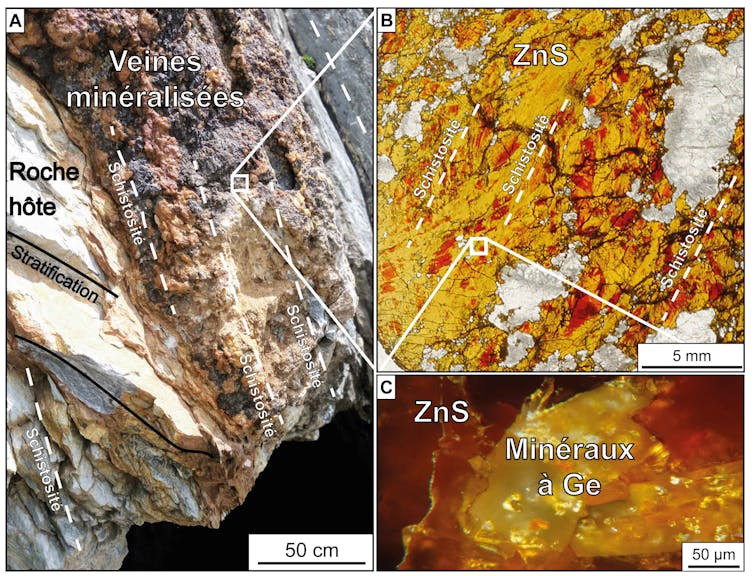

These critical metals (rare earths, cobalt, lithium, platinum group metals, germanium, etc.) are found either in minute quantities, scattered throughout base metals such as zinc and copper, or sometimes in hyperconcentrated minerals smaller than a tenth of a millimeter. To understand this fundamental difference with an everyday example, consider a single chocolate cake, with melted chocolate evenly distributed throughout the cake batter, and chocolate chips. In what form is the chocolate easiest for food lovers to recover once the cake is made? The chips, of course! The principle is the same in our study: it is easier to extract critical metals from small concentrated minerals (our chocolate chips) than from those scattered throughout the base ore (the melted chocolate in the cake batter).

The difficult supply of the metals of tomorrow

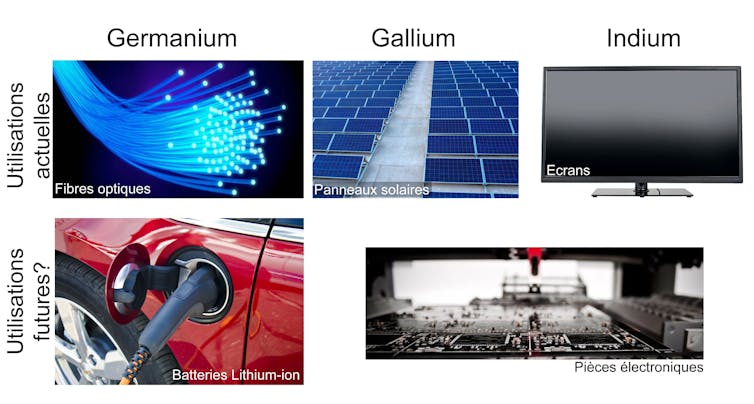

Many natural metallic substances are still mined today, such as base metals and ferrous metals (copper, zinc, iron, manganese, etc.) and precious metals (gold, silver, platinum, etc.). "Technological metals " such as lithium, rare earths, tungsten, and other rare metals (germanium, gallium, indium) have become indispensable due to the digital revolution and are also crucial for the development of "green technologies."

See also:

Why do we talk about the "criticality" of materials?

If we continue to extract these technological metals at the current rate and under these conditions, even though most of them are considered critical, we could face a supply crisis and significant environmental impacts.

Author provided

Among these critical metals, elements from the "rare earth" group, as well as lithium and cobalt, are essential to new automotive and IT technologies. Tungsten is valuable in certain aeronautical alloys. Rare metals such as gallium, germanium, and indium are essential for the manufacture of fiber optics, solar panels, and electronic systems, and could improve the efficiency of lithium-ion batteries. These metals are mainly extracted as by-products of zinc sulfide, in which they are diluted.

Where are rare metals concentrated and how can they be extracted more efficiently?

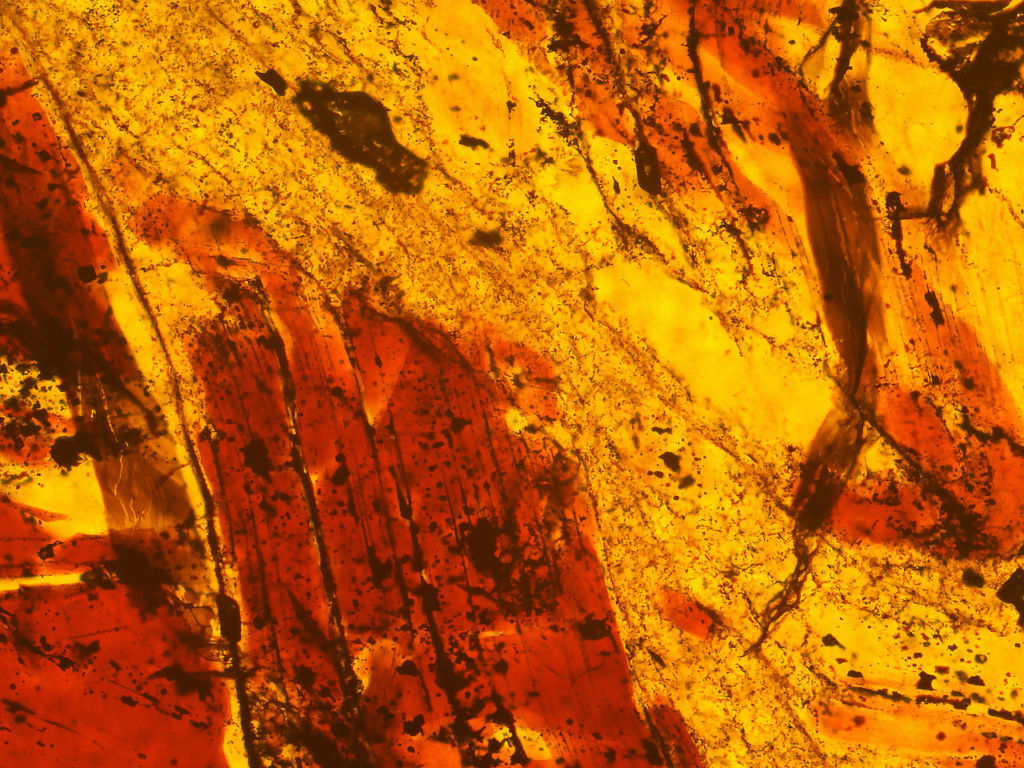

Our study shows that rare metals such as germanium, gallium, and indium can exist in minute quantities, scattered in base metal crystals, but also in small, hyperconcentrated carrier minerals. We have shown that the deformation of zinc sulfide ore, which occurs at the same time as the formation of mountain ranges, promotes the re-concentration of germanium in hyperconcentrated minerals (our chocolate nuggets) at the heart of mountain ranges, in this case the Pyrenees.

Consequently, it becomes very interesting to search for mining sites where deformation by natural geological processes has acted as a "natural concentrator" of rare metals.

Author provided

This may apply to the rare metals listed, but could also be true for other technological metals, such as rare earth elements. Many mining sites were previously exploited for their base metals (only), and today, many of the slag heaps or mining residues from this past exploitation could be recycled. There may be significant concentrations of rare metals in these mine tailings, particularly in the Pyrenees, the Massif Central, but also in the Alps and the Scandinavian mountains of northern Europe, and these may constitute potential sources of rare metals.

Furthermore, when a rare metal, such as germanium, is scattered throughout the ore,extraction is complex, requires heavy hydrometallurgical processes, and results in significant losses during extraction. However, if these rare metals are concentrated (like chocolate chips in a cake) in small minerals, their separation using various mechanical processes could be improved and better exploited, whether in current mining sites or in certain slag heaps or mining waste.

Our study suggests rapid and inexpensive techniques that can be used to characterize the mineralogical texture (crystal size and shape) and chemistry of rock samples, locate rare metals within them, and assess their concentration and potential for extraction.

Breaking free from Europe's near-total dependence on metal resources?

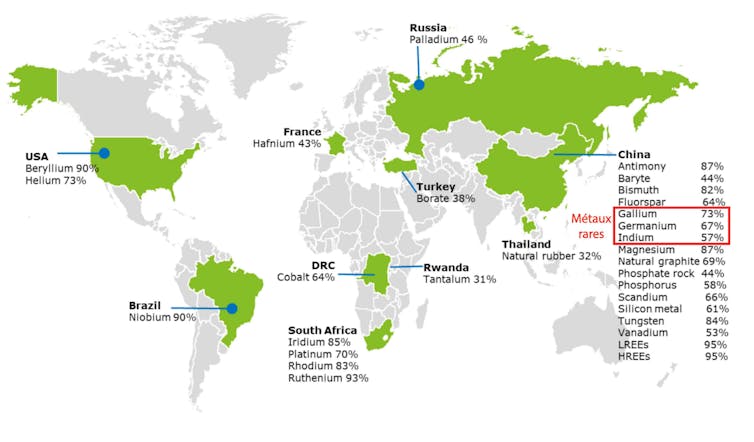

Currently, the global market for rare metals (gallium, germanium, indium) and rare earths is dominated by China. Europe is almost entirely dependent on Asia, the Americas, and Africa. But what would be the economic consequences for our industries if a crisis in the supply of mineral resources, particularly "technological metals," were to arise between our countries or continents?

European Commission

Social and environmental impacts

The importation of metal resources for our21st-century technologies, some of which have strong "green" or "renewable" connotations, from distant countries with lax or non-existent environmental regulations is particularly paradoxical.

See also:

Rare earths: our extreme dependence on China (and how to break free)

Wouldn't one solution be to extract our metals, for example from certain mining waste piles rich in critical metals in Europe, in an eco-responsible and environmentally friendly manner? We need to better understand how critical minerals form and concentrate in chemical and geological terms, which could enable us to revisit certain old mines and recover value from their mining waste piles.![]()

Alexandre Cugerone, Doctor of Geosciences – Mining Geology/Metallogeny – Geosciences Montpellier, University of Montpellier; Bénédicte Cenki-Tok, Associate Professor at Montpellier University, EU H2020 MSCA visiting researcher at Sydney University, University of Montpellier and Emilien OLIOT, Senior Lecturer in Earth Sciences, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.