Dietary supplements, meditation, osteopathy: how effective are alternative medicines?

Alternative medicine is hugely popular today. A diet here, a dietary supplement there. Herbal teas, tai chi, hypnosis techniques, psychotherapy, manual therapies, video games, connected health devices, ergonomic pillows...

Gregory Ninot, University of Montpellier

The list of products and methods offered for treatment outside of conventional medicine seems endless. Alternative medicine is now available in hospitals and in the offices of general practitioners and specialists. More than 100 million people use it in Europe, according to a survey conducted by the European CAMBrella program in 2012.

These solutions to our health problems are most often presented as effective and safe. However, not all of them are equal. Researchers around the world have undertaken to evaluate their benefits and risks to health. Already, solid results.

To make this knowledge more accessible, our team from the universities of Montpellier launched in February the very first search engine dedicated to these "non-pharmacological interventions" (NPI), called MotrialA kind of "Google for alternative medicine studies." Intended for researchers, it also allows doctors to know what to recommend, for example, to a patient suffering from back pain.

Complementary medicine or alternative medicine?

The demand for rigorous evaluation of alternative medicine has become increasingly urgent over the years. In 2011, the French National Authority for Health (HAS) called for the "development of validated non-drug therapies." In 2013, the French Academy of Medicine called for more appropriate use of "complementary therapies."

Citizens are also concerned, as shown by a survey published in 2014 by Eurocam, a foundation for complementary and alternative medicine.

There are many questions to be asked: what are the real benefits of these interventions? What risks do they pose to their users? Are they complementary or alternative to conventional treatments? Do they open the door to abuse, such as financial scams, psychological manipulation leading people to refuse conventional care, or recruitment by cults? Should they be prescribed by a doctor?

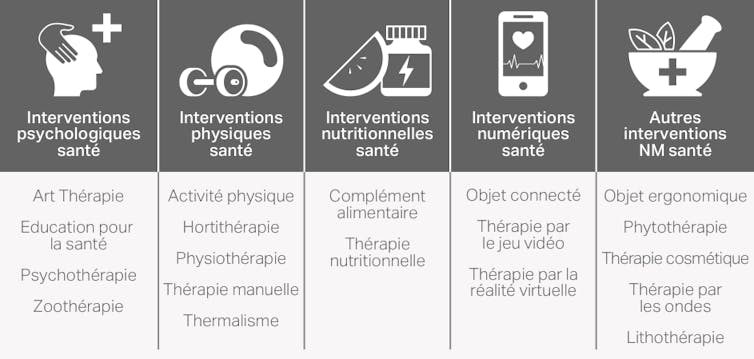

CEPS Platform, Universities of Montpellier

An effective osteopathy program for back pain

Because it would be simpler for everyone, we would like science to be able to make a definitive, global judgment on the effectiveness of each discipline. Take osteopathy, for example. This technique for manipulating joints and muscles is now well known. So, we are asked, does it work or does it not work?

There is no serious answer to such a question. However, we can attest to the positive effects of a specific osteopathic method for a given disorder, in other words, a "non-drug intervention." For example, a British study of two months of sessions given to people suffering from low back pain showed a decrease in pain intensity.

Similarly, instead of referring to "dietary supplements" in general, we need to look at a specific product, with a specific dosage over a specific period of time, in relation to a specific health problem. A team of Iranian researchers looked at aloe vera gel. They observed that a 300 mg capsule every two hours for two months in people with type 2 diabetes improved their blood sugar levels—but not their blood fat (lipid) levels.

Alternative medicine... based on evidence

Today we are witnessing the advent of evidence-based medicine, with practices supported by science. This trend encourages us to move away from the nebulous field of "alternative medicine." Non-drug interventions (NDIs) must be studied with the same rigor as drugs. Ultimately, each NDI will have a globally recognized name, a description of its content, objectives based on health indicators, a target population, an explanatory theory, qualified professionals ready to implement it, and scientific publications validating it.

Researchers evaluating these interventions are already using clinical trials—just as they would for a future chemotherapy treatment for cancer. A clinical trial is an experimental study that compares the health benefits and risks of a solution in one group of people to one or more other groups called controls or placebos. This helps to break away from the magical thinking, fads, and marketing rhetoric that too often accompany alternative medicine.

The number of these trials has been steadily increasing in NMIs since the beginning of the century. Each year, more than 50,000 new publications concern clinical studies that do not involve drugs. Their methodological quality is also improving, thanks in particular to the initiative of research groups. In France, the Interdisciplinary University College of Integrative Medicine and Complementary Therapies (CUMIC) was created for this purpose in 2018, coordinated by two professors of medicine, Julien Nizard and Jacques Kopferschmitt.

A meta-analysis on physical activity and breast cancer

Another tool for evaluating NIMs is meta-analysis. This involves a systematic review of the scientific literature, combined with statistical techniques. By combining data from all relevant studies, meta-analyses provide more reliable estimates of the effects of a treatment or prevention strategy than those from a single study. Health authorities, national agencies, and learned societies rely heavily on these meta-syntheses to issue their recommendations.

For example, the meta-analysis published in 2013 by our laboratory, Epsylon, focused on the amount of physical activity needed to reduce fatigue during breast cancer treatment. This work shows a decrease in fatigue experienced by women if they engage in less than two hours of physical activity per week. This meta-analysis is based on 17 studies involving a total of 1,380 patients.

Another example, also in breast cancer, concerns psychotherapy. A meta-analysis published in 2017 by a German team looked at mindfulness meditation practiced in addition to biological treatments for the tumor. This is the method developed by American John Kabat-Zinn, an 8-week program designed to reduce stress (Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction or MBSR). Conclusion: compared to standard care alone, this program provides additional benefits by addressing anxiety and depression. This meta-analysis was based on 10 studies involving a total of 1,709 patients.

Behavioral therapy more effective against depression than light therapy

This tool also allows INMs to be compared with each other. For example, the meta-analysis by a Dutch team published in 2017 combined 11 studies (including 1,041 patients) on different ways of treating depression in general practice. Between cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a physical activity program, problem-solving psychotherapy, a behavioral change program, and light therapy, the authors conclude that CBT appears to be preferable—while encouraging further studies to confirm this result.

However, this meta-analysis work proves particularly time-consuming and difficult to carry out when it comes to INMs. That is why we launched the Motrial meta-search engine, with the aim of saving researchers time.

Motrial sorts and organizes scientific publications by identifying the main publication, the ethics committee declaration number, the protocol registration number with the relevant authorities, the sources of funding, the name of the sponsor, and the country where each study was conducted. It automatically completes in six minutes what could take six months to do manually.

![]() Scientists are gradually acquiring tools that can help them distinguish between fact and fiction when it comes to the effectiveness of various alternative medicines. The hopes they raise are immense. For this reason alone, they must be evaluated with the same rigor as drugs or other biotechnological treatments.

Scientists are gradually acquiring tools that can help them distinguish between fact and fiction when it comes to the effectiveness of various alternative medicines. The hopes they raise are immense. For this reason alone, they must be evaluated with the same rigor as drugs or other biotechnological treatments.

Gregory NinotProfessor of Health, Psychology, and Sports Science, University of Montpellier

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.