Understanding the mechanisms of adaptation to climate change: a real challenge

Increasing urbanization, intensive agriculture, overexploitation of resources, introduction of exotic species, and climate change: all these environmental changes constitute an explosive cocktail for biodiversity.

Céline Teplitsky, University of Montpellier; Anne Charmantier, National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and Suzanne Bonamour, Sorbonne University

In light of these changes, certain questions arise frequently: Will wild species be able to adapt to such rapid and extensive changes? Will the adaptations observed enable us to preserve part of the world's biodiversity?

Over the past few decades, our understanding of how living organisms adapt to their environment has changed dramatically.

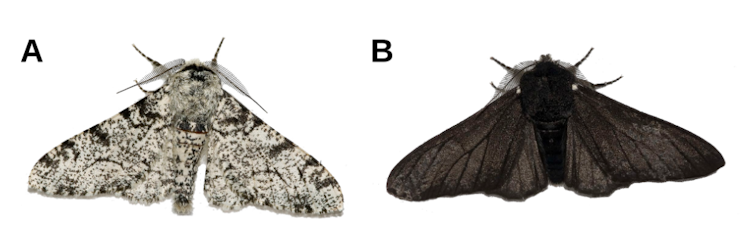

For a long time, it was thought that species evolved over very long periods of time, before it was realized that evolution could be very rapid, as evidenced, for example, by the evolution of antibiotic resistance in human pathogenic bacteria, or the evolution of coloration in a common butterfly, the peppered moth, following the blackening of tree bark due to heavy air pollution in England in the 19th century.

Vincent Guili, CC BY-NC-SA

Evolution and plasticity

Living organisms adapt to changes in their environment (such as decreased rainfall or the presence of a new predator) through two major processes: genetic evolution and/or phenotypic plasticity.

Adaptation through genetic evolution occurs through changes in the genetic composition of the population over generations under the influence of natural selection. For example, mosquitoes carrying a new mutation that appeared in the 1980s are much more resistant to insecticides than other individuals that do not carry this genetic innovation. As a result, this mutation and the insecticide resistance it provides have spread throughout natural mosquito populations in about two decades.

This process of adaptation through genetic evolution requires that the selected traits (resistance, for example) be at least partially "heritable"—that is, transmissible between generations, from parents to children—and genetically variable. It is important to note that since genetic changes occur between generations, genetic evolution is faster when the generation time of the species is short: thus, mosquitoes can adapt to a new environment more quickly than whales.

A second adaptation mechanism is "phenotypic plasticity."

While genetic evolution is a process that induces changes between generations in a given population, phenotypic plasticity is a process of adaptation that can induce changes within each individual in the population.

For example, in many mammals, the amount of adipose tissue in an individual can vary depending on several environmental factors, particularly cold temperatures. Similarly, many species increase their vigilance when the risk of predation is high.

Plasticity therefore manifests itself within a generation, enabling faster adaptations than genetic evolution. In particular, it allows the organism to readjust in response to changing environmental conditions throughout an individual's lifetime.

Organisms often need time to prepare for new environmental conditions: if the plastic response is to develop a defense against predators, this must be put in place well before encountering the predator. Organisms therefore use cues present in the environment to develop the appropriate response at the right time. This is the case with tadpoles, which develop different morphologies depending on whether or not the scent of a predator is present.

In the current context, the existence of a mechanism such as phenotypic plasticity, which is widespread in the living world and can enable very rapid adaptation to environmental changes, is of major interest in understanding and anticipating the consequences of anthropogenic disruptions on biodiversity.

Laying eggs at the right time

The blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus), a small passerine bird, is widely studied in the field of ecology and is the subject of numerous research projects based on observations of natural populations.

Research on this species has contributed to a better understanding of the importance of phenotypic plasticity for the adaptation of organisms to climate change.

Studies in the natural environment, some of which have been ongoing for several decades, have given us a better understanding of the ecology of the blue tit. In this species, as in most other insectivorous passerines living in temperate forests, chicks are mainly fed caterpillars by both parents—approximately 1,800 caterpillars to feed a single chick from hatching to fledging.

Lumiks Lumiks/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Thus, the synchronization between the chicks' food requirements and the period of caterpillar abundance has a major impact on the chicks' survival. In order for the chicks to be born at the right time, i.e., when the parents will be able to find a large quantity of caterpillars to bring back to the nest, the female chickadee must lay her eggs about 30 days before the peak abundance of caterpillars in the forest.

But how do you lay eggs at the right time?

The laying date for chickadees, as for many birds, depends in part on the environment and particularly on temperature: in warm years, chickadees lay their eggs earlier than in cold years, perfectly illustrating the concept of phenotypic plasticity.

The period during which chickadees are most sensitive to temperature, i.e., the period when birds pick up signs of a more or less warm and early spring, can vary between one and three months before breeding. Depending on the population, this period of temperature sensitivity begins in spring or late winter. The reliability of temperature as a predictor of the period of food abundance (caterpillars) is crucial for reproductive success.

Plasticity in response to temperature is common. Faced with global warming, many animal and plant species are reproducing earlier and earlier each year, just as trees are budding earlier. These changes in life cycles, linked to organisms' response to temperature changes, can already be observed in our gardens and forests.

Plasticity therefore largely explains what we refer to as increasingly early springs. Plasticity related to phenology—that is, the calendar of events throughout the year, such as the date when chickadees lay their eggs—is in fact one of the main responses of wild species to climate change.

However, little is known about how global changes may affect this response and test the limits of adaptation. Is it possible for species to adapt quickly to these unprecedented and stressful environments? A recent study suggests that phenological plasticity may already be insufficient to allow populations to persist.

See also:

Climate change and the biodiversity crisis: a dangerous alliance

New and stressful disruptions

Many scientific questions remain unanswered regarding the adaptation of animals to climate change.

What happens when environments become too different from those historically experienced by organisms? In particular, how does adaptation to gradual climate change enable organisms to cope with extreme weather events such as heat waves? How will differences in responses between species affect their interactions (e.g., between prey and predators or between cooperating species)?

Caterpillars are developing earlier and earlier in response to climate change, but is there a limit for chickadees, a date before which it is physiologically impossible to begin reproducing, preventing synchronization with their prey? How do global changes affect the reliability of the information organisms need to respond to the environment?

For example, when they hatch, young sea turtles often head toward cities rather than the sea, as urban lights are brighter than the moon. Can this type of misinterpretation limit or even negate the benefits of plasticity?

Finally, will organisms be able to cope with multiple environmental changes thanks to phenotypic plasticity? In addition to climate change (changes in temperature and precipitation), organisms are faced with multiple disturbances—new pathogens and predators, the presence of pesticides, urban development, etc.

Our research project, "Mommy Knows Best," aims to assess whether limits to plasticity are already detectable in natural populations, using the blue tit as a model species. We will test the effect of various environmental factors on the plasticity of egg-laying dates in blue tits (such as the effect of urbanization or agricultural practices, for example) and model the effects of plasticity on blue tit population dynamics in order to understand the extent to which changes in plasticity can affect the risk of population extinction.

The findings of this project may also shed conceptual light on the process of phenotypic plasticity in the context of climate change, and be applied to other wild species.

Understanding the limits of adaptation in the face of global change will provide a better understanding of the scale of the challenge currently facing biodiversity... But there is no need to wait to combat its destruction, which is already underway!

The "Mommy knows best" research project, of which this publication is a part, received support from the BNP Paribas Foundation as part of its Climate and Biodiversity Initiative program..![]()

Céline Teplitsky, Researcher in evolutionary ecology, CNRS, University of Montpellier; Anne Charmantier, Director of Research in Evolutionary Ecology, National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and Suzanne Bonamour, Postdoctoral Researcher, National Museum of Natural History, Sorbonne University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.