Conversation with Mircea Sofonea: "In France, control of the epidemic is still fragile"

On May 3, we entered the first phase of a four-phase plan to lift lockdown restrictions. The second phase, which will begin on May 19, should see the reopening of restaurants, terraces, cultural venues, and sports facilities. On the eve of these easing measures, what is the current state of the epidemic?

Mircea T. Sofonea, University of Montpellier

What can we expect from its evolution, and what could be the impact on hospital pressure? Answers from Mircea Sofonea, senior lecturer in epidemiology and infectious disease evolution at the University of Montpellier.

The Conversation: We have experienced three lockdowns in one year. How does this latest episode compare to the previous ones?

Mircea Sofonea: Based on hospital data and genetic analysis of samples collected in our country, it would appear that the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in France began during the second half of January 2020.

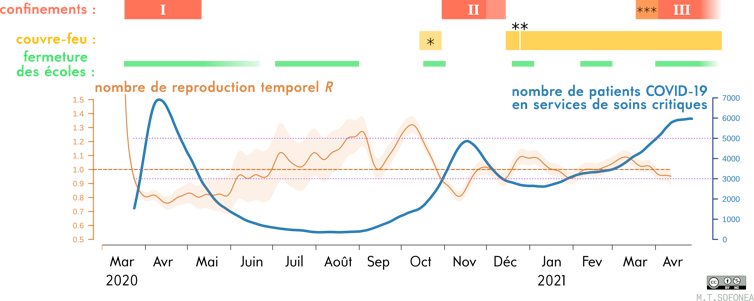

In the spring of the same year, an initial strict eight-week lockdown had reduced the number of new daily cases (actual) to 4,000 per day by the time restrictions were lifted. France then experienced a lull during the summer, before suffering a second wave in the fall, which led to a second national lockdown in October 2020—even though the benefits of early, localized measures were already well documented. This second lockdown was not intense or long enough to bring the incidence back below 5,000 new (detected) cases per day, mainly because viral circulation among children was underestimated and because of the easing of restrictions associated with the end-of-year celebrations.

See also:

What do we know about the role of schools in the COVID-19 pandemic? Five experts respond.

From that point on, the executive branch opted for a strategy that differed from that of its neighbors in managing the epidemic, tolerating substantial circulation of the virus, accompanied by a high level of hospital occupancy. In addition to this intermediate level of control, social restrictions, such as curfews, were maintained. This choice was motivated by the hope that there might be a "loophole" that could be exploited to minimize both the economic and health impact at every stage of the epidemic. This hope proved illusory, as subsequent events showed.

Sofonea M. T., et al. (2021) Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine, Author provided

This strategy was continued in early 2021, despite the arrival of the more contagious "British" variant, whose dynamics were documented relatively early on. As a result, a third national lockdown had to be imposed on April 3. Schools were closed for three weeks (including two weeks of school holidays) and relative freedom of movement was maintained.

TC: Has this third lockdown achieved its objectives?

MS: As we pointed out in an article recently published in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine (the official journal of the French Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care), lockdown has two objectives: to cap hospital occupancy in order to prevent a deterioration in care, and to regain control of the epidemic by minimizing its incidence, in other words by reducing the number of new cases per day to a level low enough to be maintained by an intensive strategy of screening, tracing, and isolation.

Arriving late, this third lockdown was not as effective as the previous two (due in particular to the high contagiousness of the predominant circulating variant, B.1.1.7). It was also relatively short. However, we know that the longer we wait before taking action, the higher the levels of virus circulation and hospital occupancy will be, and therefore the longer it will take to return to acceptable levels in terms of controlling the epidemic (low incidence, low hospital occupancy). At the end of the second lockdown, hospital occupancy, particularly in critical care units—which have been under relentless pressure for 14 months—had not returned to the low levels seen during the first lockdown.

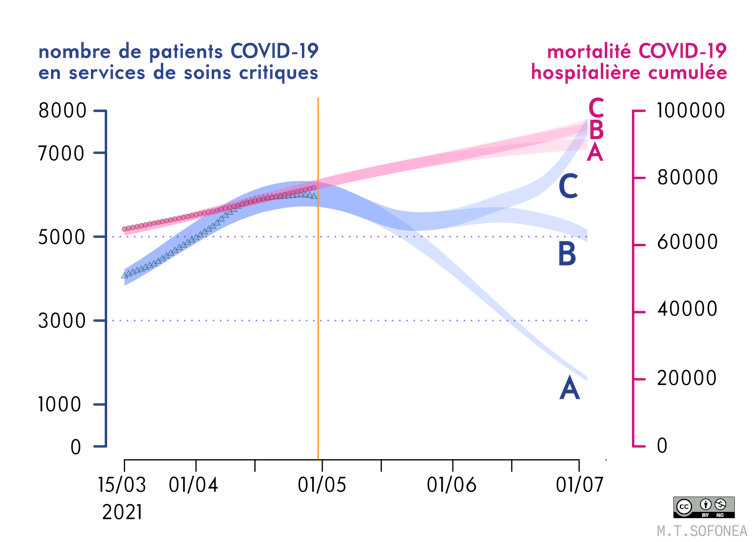

This new lockdown has successfully achieved its primary objective—capping hospital occupancy: currently, there are approximately 5,600 COVID patients in public intensive care units.

However, the second objective has not really been achieved: the reproduction number calculated three weeks after the start of the third lockdown was around 0.95 – but it has fallen since then (editor's note: also known as the "effective R," the reproduction number is an estimate, over the last seven days, of the average number of individuals infected by one infected person). After the first lockdown, this number had fallen to around 0.8 in two weeks – kinetically speaking, the epidemic decline in the first two weeks of the third lockdown was therefore more than three times slower.

Under these conditions, it would take several more weeks to return to a level of 3,000 new cases per day, as was the case during the first lockdown easing a year ago.

TC: Announcements have been made regarding the end of this third lockdown. What could happen now, according to your models?

MS: In a way, the epidemic trajectory that the country has been following since October has led us to a kind of impasse.

On the one hand, epidemic control is still too fragile and relies heavily on individual responsibility. On the other hand, we all want to return to our pre-pandemic habits and lives. We are tired, if not exasperated, by the restrictions, and even maintaining them could be met with resistance and circumvention.

The only prospect, therefore, seems to be acceptance of the morbidity and mortality toll caused by a third wave that is slowly subsiding. It should be remembered that the health issue is not limited to deaths due to Covid (too often used as the sole quantifier), but also to quality of life after intensive care, long Covid, and pathologies whose diagnosis and treatment have been delayed by postponements following the rise of the third wave (particularly in Île-de-France and Hauts-de-France).

TC: But this time, the vaccine is available. And the warm weather is coming...

Fortunately, vaccination coverage has a significant effect, but it is not yet sufficient to stop the epidemic on its own. According to our model, which takes into account increased transmission of variants but not potential immune escape, herd immunity would require vaccination coverage of 70% of the population (i.e., more than 90% of the adult population), but at present we are at 25% for the first dose.

As for sunny days, they can be conducive to reducing transmission as long as they are accompanied by a lifestyle that favors spending time outdoors and in constantly ventilated homes. However, if we look at the history of the reproduction number since the first lockdown was introduced, we can see that there have been two peaks in contagiousness with a reproduction number above 1.3: in August and October. Here again, we cannot say that summer weather is a guarantee of absolute control.

During social events, even if most of the time is spent outdoors, a brief gathering indoors (in the kitchen) without masks remains an opportunity for transmission. Crowded terraces where people talk loudly (against a noisy background), shoulder to shoulder, also expose us to infectious aerosols, even if they dissipate much more quickly than indoors.

Ultimately, the dynamics of the coming weeks will once again depend on our collective compliance with protective measures, combined with the three-pronged approach of testing, tracing, and isolating.

TC: With all these uncertainties, how can we assess what might happen?

MS: It is very difficult to make predictions beyond two weeks, given the uncertainties surrounding the synergy of the various measures. However, we can use previous lockdown easing measures as a basis for exploring scenarios, which then give rise to projections based on assumptions.

In the first case, if the contact rate (the number of contacts between people per unit of time) were similar to that in October, the incidence would increase slightly before beginning a slow decline, mainly due to increased vaccination coverage. In this scenario, the number of patients in intensive care would not fall below 4,000 before July.

Sofonea M. T., et al. (2021) Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine, Author provided

In the second scenario, if the contact rate were even 10% higher than in October, the epidemic could rebound, putting intensive care units under severe strain once again as early as mid-June, after reaching a low point at the end of May with around 5,000 patients hospitalized in critical care.

TC: How did the other countries that have been most successful in controlling the epidemic proceed?

MS: The countries that have fared best have done everything possible to bring the epidemic under control as quickly as possible, then resumed normal life: this is the case in South Korea, New Zealand, and Taiwan, for example. However, it cannot be denied that they benefited from more favorable conditions.

Compared to countries that have aimed for elimination, it can be said that France has, since last summer, chosen to minimize the number of lockdown periods rather than the number of lockdown days, resulting in a suboptimal stop-and-go approach that has not minimized the spread of the virus. It is better to impose more lockdowns, but make them short and localized, as New Zealand did with Auckland (or China did with Beijing, for example), in order to break the chains of transmission at a very early stage.

Furthermore, by not significantly reducing the incidence before relying on vaccination coverage to control the epidemic (as the United Kingdom, Portugal, and Denmark have done, for example), the possibility of local resurgences in early summer cannot be ruled out in France. Another disadvantage of vaccinating when incidence is high (and therefore viral diversity is naturally greater) is that there is a greater risk of variants emerging that are better equipped to circumvent natural or vaccine-induced immunity. If vaccination is carried out when the virus is circulating very little, this risk is lower.![]()

Mircea T. Sofonea, Associate Professor of Epidemiology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases, MIVEGEC Laboratory, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.