COVID-19: An unpredictable winter marked by the massive and unprecedented spread of Omicron

Mircea T. Sofonea, University of Montpellier and Samuel Alizon, National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS)

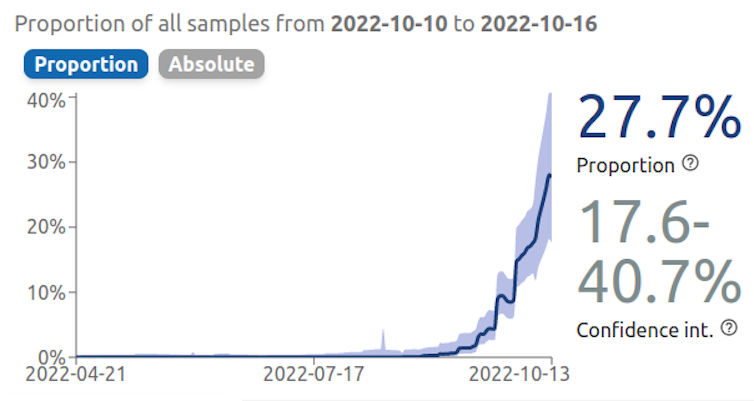

A certain "pandemic fatigue" has taken hold among part of the population, but SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve. As France experiences its eighth wave (the fourth in 2022), dominated by the Omicron BA.5 subvariant, another subvariant, known as BQ.1.1, is rapidly gaining ground. Samuel Alizon, research director (CNRS, CIRB), and Mircea Sofonea, senior lecturer (University of Montpellier, MIVEGEC), review the health situation expected this winter and highlight the challenges of surveillance and research in our country. What are the consequences?

The Conversation: With the end of summer, Covid and its variants are back in the news. Now it's BQ.1.1 and other XBB variants that are being discussed. What can we already say about these "sub-variants"? And how are they being monitored?

Samuel Alizon: Since September, we have seen significant diversification of SARS-CoV-2, with the emergence of numerous sub-variants of the Omicron variant.

BA.4.6, BA.2.75, BA.5.2, and even B.1.1.529.5.3.1.1.1.1.1, renamed BQ.1.1 according to the Pango nomenclature, which proposes an identification system to track SARS-CoV-2 genetic lineages of epidemiological interest...

All of these lineages, which are prevalent in various regions of the world (BQ.1.1, for example, is currently spreading rapidly in France), officially belong to the Omicron variant. They are therefore sub-variants, but in reality, they could easily be classified as variants.

TC: What do we know about these new sub-variants? Do they pose an epidemiological threat?

SA: At this stage, much of what we know about these new strains should be treated with caution, as it is, at best, based on pre-publications that have not been peer-reviewed. Little is known about their virulence and, of course, virtually nothing about the long-term effects of infection.

However, we are certain about the mutations present in the genomes of these lineages, since they are what define them. For example, the BA.5 variant had fixed a mutation at position 452 of the Spike protein. This was widely studied because it was characteristic of the Delta variant when it first appeared.

For BQ.1.1, we see a whole other series of mutations in the receptor binding domain (RBD) of this protein, in other words the part of the spike protein that interacts with ACE2, the "lock" located on the surface of the cells infected by SARS-CoV-2. This is particularly the case with the S:R346T mutation. As indicated in a pre-publication by a consortium of Chinese teams, these mutations appear to confer significant immune evasion potential to this lineage. In addition, BQ.1.1 may not be sensitive to monoclonal antibody treatments available in France (such as the tixagevimab-cilgavimab combination (Evusheld)).

Among the sub-variants being monitored, particularly due to their potential immune escape capabilities, we can also mention the XBB lineage, which is the result of a recombination between the BJ.1 and BM.1.1 virus lineages during co-infection of the same cell.

TC: How are these variants of concern monitored? Where does the epidemiological data come from?

SA: From an epidemiological standpoint, the quality of the British surveillance system remains outstanding. Their latest report, dated October 7, 2022, which combines testing and sequencing data, provides a particularly clear picture of their epidemic situation.

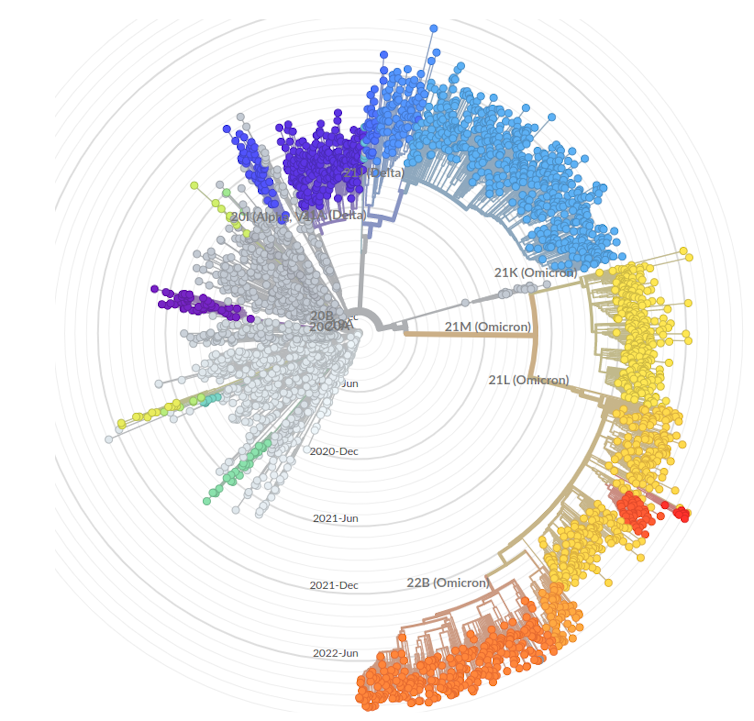

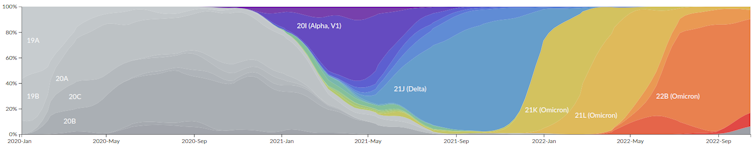

For other countries, including France, we rely on sequencing data shared on the GISAID platform. Several websites, including Nextstrain.org and the excellent covSPECTRUM from Prof. Tanja Stadler's team in Switzerland, allow users to view the dynamics of variants in real time (within the limits of the data provided by each country).

Mircea Sofonea: It should be noted that, unlike previous waves caused by the arrival of a new variant, screening data from RT-qPCR tests (which identify predefined mutations and are therefore used to track already known variants) no longer allow these new lineages to be distinguished .

This deprives us of an early and therefore valuable signal to inform models in real time about current replacement dynamics. This can then only be known through sequencing, with a delay of at least one week after sampling (which itself occurs several days after the onset of infection) and on a sample that, for material reasons, is reduced – Flash surveys conducted by the EMERGEN consortium covering 1,000 to 2,000 interpretable sequences.

The problem is that, this time around, France is the first country to experience the predominance of the new (sub-)variant (BQ.1.1). We can therefore no longer rely on the trends observed across the Channel!

While the genetic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 is once again putting our surveillance and healthcare system to the test, the technical and scientific chain, from individual sampling to population analysis, on which our collective anticipation relies, needs immediate investment commensurate with the public health challenge. https://cov-spectrum.org/embed/VariantInternationalComparisonChart?json=%7B%22variantSelector%22%3A%7B%22location%22%3A%7B%7D%2C%22dateRange%22%3A%7B%22mode%22%3A%22Past6M%22%7D,%22variant%22%3A%7B%22nextcladePangoLineage%22%3A%22bq.1.1*%22%7D,%22samplingStrategy%22%3A%22AllSamples%22%7D,%22countries%22%3A%5B%22France%22%5D,%22logScale%22%3Afalse%7D&sharedWidgetJson=%7B%22originalPageUrl%22%3A%22https%3A%2F%2Fcov-spectrum.org%2Fexplore%2FFrance%2FAllSamples%2FPast6M%2Fvariants%3FnextcladePangoLineage%3Dbq.1.1*%26%22%7D

TC: How do these variants fit into the overall evolution observed for Omicron?

SA: Until then, we often had one dominant lineage and fairly pronounced replacements of variants: Alpha replaced all the lineages that preceded it, then Delta replaced Alpha, and so on.

There, as can be seen on the Nexstrain.org website, sub-lineages derived from BA.2, BA.4, and BA.5 appear to be co-circulating globally.

As for the reasons behind this diversification, it is obviously impossible to be certain. The study of biological diversity is a field in its own right, but two hypotheses can be put forward.

On the one hand, parasite diversity often correlates with that of their hosts. However, human populations are now more diverse than ever in terms of their immunity, whether acquired through vaccination or post-infection.

On the other hand, the diversification of the virus is also proportional to the number of new infections, and currently, in many countries, the virus is circulating uncontrollably.

[More than 80,000 readers trust The Conversation newsletter to help them better understand the world's major issues. Subscribe today]

TC: Could we have expected such a situation?

MS: While it is impossible today, and will certainly remain so for many years to come, to predict the precise evolutionary trajectory of a coronavirus, the diversification dynamics observed since the spring are not necessarily surprising.

The first two years of the pandemic were marked by strong selection pressures on transmission—Alpha and Delta were only able to emerge because their particularly high contagiousness allowed them to compensate for social distancing and masks.

Omicron, which originated from an old branch of the SARS-CoV-2 phylogenetic tree and not from these two variants, spread in a context where population immunity (post-infectious and vaccine-induced) had become an additional barrier to viral spread. Since spring 2022, this immunity has been the only remaining barrier.

Thanks to its combination of high contagiousness and strong immune escape, Omicron BA.1 has virtually driven other lineages to extinction and benefited from virtually unrestricted circulation, apart from the humoral and cellular immunity developed against them.

However, since each infection is a source of (random) mutations, the conditions were right for setting up a "treadmill" of diversification fueled by immune escape.

TC: So is this capacity for diversification endless?

SA: This question invites us to revisit the debates of 2020 and even 2021, when some people were predicting that the virus would "run out of steam" and its potential for mutation would diminish.

In fact,viral evolution is always difficult to predict because each mutation can completely change the virus's "adaptive landscape," i.e., its potential for evolution. In addition to genetic constraints, there are also environmental constraints and the variability of populations infected with the virus.

An interesting point in the current diversification of viral lineages is that there are a number of cases of parallel evolution, i.e., lineages that independently fix the same mutation.

TC: What are the potential consequences for this winter? Are forecasts still possible?

SA: It's very difficult, because beyond the scientific challenge, research teams in France have virtually no annual core funding (known as "recurring" funding), and many projects have been rejected this year. In short, we are no longer in a position to explore prospective scenarios. And unlike in 2020 and 2021, there is no longer a scientific council to request such analyses. The unknowns about how the winter will unfold are therefore enormous.

What we can say, however, is that the current wave (which began in mid-September) is still dominated by the BA.5 lineage, which had already caused the third epidemic peak of 2022 in July. This fourth wave probably has multiple origins, but it is worth noting that it coincided with the start of the school year and was initially observed among children.

As for why the same variant was able to generate a new wave so soon after the previous one, it is likely that social factors were decisive. The summer probably broke the previous wave, and the start of the school year favored the resumption of viral circulation. The persistence of post-infection immunity from the summer wave for BA.5 probably explains why the peak was reached so quickly for children (before the end of September).

For adults, the epidemic logically started later and spread from the epidemic among children. Unfortunately, the peak of the epidemic was slow to emerge this time. The sequencing data is still incomplete, but as suggested by the visualizations on the covSPECTRUM website, the rise of the "new" variants mentioned above (such as BQ.1.1) could be the cause.

If this is confirmed, there could be fears that a fifth wave in 2022 could overlap with the fourth, even though the school holidays should help to ease the situation. In the absence of a national vaccination campaign, the scale of this wave would be directly correlated with immune escape or, more precisely, with the intensity of cross-immunity between BA.5 and new variants.

MS: Short-term forecasts (i.e., two weeks ahead) are always possible by exploiting the inertia of the epidemic and the history of past waves. The current eighth wave is so far within the average range of previous waves in terms of intensity and duration.

However, monthly projections require certain assumptions to be made, particularly regarding the kinetics of post-infectious and post-vaccination immune decline, which has been altered by new sub-variants... These cannot be accurately determined at present, while inferences based on hospital and screening data are increasingly difficult to make and, unfortunately, there is a lack of support for developing more automated and robust approaches.

TC: Winter is also the peak season for other epidemics... Are there any commonalities between influenza and COVID epidemics?

SA: Yet another issue that makes us regret the lack of support for epidemiological modeling teams in France! Yes, the co-circulation of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 is a concern this year because initial data from the Southern Hemisphere suggest that, unlike in 2021 and, above all, in 2020, we are likely to see "normal" influenza circulation.

There are two types of effects to be concerned about: some direct, as co-infection with both viruses may be more virulent, and others indirect, with hospital capacity at risk of becoming overwhelmed more quickly.

MS: Influenza began circulating again last year, and the previous season was particularly unusual, with a late peak in March-April, just as we were gradually relaxing our vigilance and protective measures against SARS-CoV-2 (wearing masks, hand washing, etc.)—measures that also prevent the transmission of the influenza virus.

Currently, influenza circulation indicators in mainland France (with Réunion and Martinique in the epidemic phase) are comparable to pre-COVID-19 pandemic values.

Betweenthe current bronchiolitis epidemic, which is affecting the entire mainland, and the upcoming flu season, the potential ninth wave of COVID-19 will further complicate the work of healthcare workers who have been struggling for nearly three years under intense pressure.

There is an urgent need to strengthen the means of surveillance, anticipation, and simultaneous control of respiratory viruses. The methodological challenges posed by this public health issue are very specific, and unfortunately, we do not currently have the means to address them.

While it is entirely legitimate and desirable—particularly in order to avoid exacerbating "pandemic fatigue"—that daily attention should not be focused on Covid, it is nevertheless essential that, in the background, we support this transition towards controlled endemic circulation, rather than the current situation where we are simply enduring it. Research can help bring this goal closer.

Mircea T. Sofonea, Associate Professor of Epidemiology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases, MIVEGEC Laboratory, University of Montpellier and Samuel Alizon, Director of Research CNRS and Director of the Ecology and Evolution of Health team at the Interdisciplinary Center for Research in Biology (CIRB) UMR 7241 – U1050 Inserm, National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.