From Abidjan to Jakarta, how cities are reinventing our meals

"Junk food," "fast food," "McDonaldization" of the world: the most negative perceptions of food are often linked to urban areas.

Audrey Soula, University of Montpellier; Nicolas Bricas, CIRAD and Olivier Lepiller, CIRAD

Anthony Bourdain and Barack Obama in a canteen in Hanoi, Vietnam (May 23, 2016). Pete Souza/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-ND

The city would thus be the place par excellence for dietary, nutritional, and epidemiological transition, for "empty calories" and ultra-processed products. It would be, by association, responsible for obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, diet-related cancers, and increasing poisoning from chemical residues.

A privileged space for commercial consumption and the industrialization of food through its supermarkets, where numerous products imported from international markets compete, the city embodies the "Walmartization" of the world.

Because the West experienced this process before other regions of the world, and because large food companies originated there, some people equate this development with the Westernization of food. The nutritional structure of diets is certainly changing in the same direction everywhere, albeit at varying speeds: the proportion of carbohydrates in energy intake is decreasing, that of lipids is increasing, and animal proteins are replacing plant proteins, while the consumption of industrially processed products is taking off.

However, eating is not limited to consumption. Although influenced by global trends, individuals' eating habits are also dependent on their perceptions, their surroundings, and their local roots.

Socio-anthropological studies that focus on detailed observation not only examine what people eat, but also how they organize themselves to do so, what they say about it, and what they think about it. Eating is much more than just nourishment, even for the most vulnerable populations. It is about enjoying oneself, maintaining ties with others, forging relationships with one's environment, and building and marking individual and collective identities.

City dwellers subject to conflicting injunctions

When it comes to food, city dwellers are influenced by multiple normative prescriptions, which they constantly navigate and which can even be contradictory.

For example, Mexicans are subject to a paradoxical injunction. The Ministry of Tourism and Economy has adopted a strategy of promoting Mexican street food, which was added to UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2019.

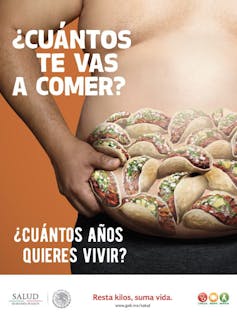

Obesity prevention campaign by the Mexican Ministry of Health. Author provided

At the same time, many discourses promote health and nutritional standards that sometimes clash with this cuisine, blaming it for cardiovascular disease and obesity.

It is easy to imagine the concern that may arise from the contradiction between these two normative registers.

But on closer inspection, we see that nutritional standards are interpreted differently depending on social background, and that individuals deal with this contradiction between nutrition and heritage according to their dietary situations, in a general context where eating Mexican food remains very popular.

South-South channels

It is true that cities in Africa, Latin America, and Asia are seeing the development of international supermarket and fast food chains.

The first supermarket in Hanoi, for example, opened in 1998. Today, the city has dozens of them, including a huge mall with nearly 150 stores, owned by the Korean chain AEON, which opened in 2015.

A Hungry Lion sign, a South African fast food chain, here in Cape Town, South Africa, 2019. Discott/Wikimedia, CC BY

Another example is Hungry Lion, a South African fast-food chain created in 1997 based on the KFC model, which now has nearly 200 restaurants in southern Africa. It is owned by Shoprite, the largest food retailer in Africa with nearly 3,000 outlets, also of South African origin. But the evolution of their food systems is far from being limited to this industrialization.

The urban popular economy invents new cuisines

The urban popular economy remains largely dominant in feeding the urban population and is constantly inventing new practices and new cuisines, far removed from the strategies of the major economic players.

In Jakarta, Indonesia, kampungs (literally "villages") are poor neighborhoods dominated by a so-called "informal" economy.

These areas are characterized by heavy traffic and a constant mix of people, many of whom are recent immigrants from rural areas, as well as by a high degree of overcrowding. Many residents do not cook at home due to a lack of equipment, skills, space, or time.

A particular type of food establishment has developed in these neighborhoods: warung makan, which offer inexpensive, home-cooked meals.

A "warung makan sate kerbau/sapi Jepara" restaurant in Indonesia. Midori, CC BY-NC-ND

These businesses, which are a kind of public kitchen where customers serve themselves, bring their own dishes, and enjoy flexible payment terms, help to preserve eating habits that are perceived as traditional and domestic, while facilitating the maintenance of community food socialization.

The distinctions between the domestic world and the commercial world, public space and private space, are blurred here, inviting us to reconsider the scale of analysis of food, which in this case relates less to the home or household than to the housing block or neighborhood.

The invention of truly urban kitchens

Popular cuisine is a melting pot of culinary innovations where compromises between various normative injunctions are combined and constructed.

Often originating from the working classes, these new urban dishes are also gaining popularity among the middle classes and, for some, have become symbols of identity for an entire city or even a country. This is the case withattiéké-garba in Abidjan, Ivory Coast.

A garbadrome in Cocody, YouTube.

This popular dish, which originated in restaurants frequented by young people near universities, known as garbadromes, was initially created in opposition to hygiene standards perceived as non-African. By eating garba, diners assert an urban, Ivorian, and transgressive identity. This dish consists of low-qualityattiéké (cassava couscous), garnished with pieces of fried salted tuna and served "wet," i.e., generously drizzled with frying oil, ideally browned by successive cooking, as a guarantee of quality!

Despite regular criticism labeling it as Ivorian "junk food," particularly due to accusations about the questionable hygiene of the dish and the establishments where it is served, garba is recognized as a dish of choice in popular restaurants.

Originally sold by Nigerian immigrants attracted by the dynamism of the Ivorian capital and embraced by urban students, garba has now become emblematic of Abidjan's identity, and even that of Côte d'Ivoire as a whole.

Preparation of babendâ.

In Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, it is bâbenda, originally a rural dish specific to the Mossi ethnic group, which is gradually gaining status as a dish that represents the identity of the entire city, but in a different way.

It was a dish made from the last remnants of millet combined with the first leafy vegetables of the new rainy season. Improved versions, using pounded corn or broken rice instead of millet, are now available and consumed by ethnic groups other than the Mossi, thanks to their greater availability in towns.

Some dishes are lost, others are created

Highlighting the creativity of cities in Africa, Latin America, and Asia, and their ability to invent their own food systems, can lead to opposition to a vision that emphasizes these cities' dependence on international markets and capital and the Westernization of the world.

In reality, these two trends are intertwined. While so-called "traditional" dishes are disappearing, new dishes are being invented.

"Obama Combo," menu from the popular restaurant where Barack Obama had lunch in Hanoi. O.Lepiller, Author provided

Admittedly, globalized food cultures and practices are visible in cities in the Global South, but this does not correspond to a simple erosion of local food repertoires.

Globalized products are certainly spreading, but they are used differently depending on the city and, within cities, the social milieu. In India, for example, Maggi instant noodles, associated with a desirable Western modernity, have found their place in middle-class practices by relying on the commercial figure of "Maggi Mom," which has helped to remove the guilt associated with saving time, which could be seen as a transgression of the role of the nurturing and loving mother.

In 2009, advertisement for Maggi noodles (Nestlé) with vegetables, a "healthy" and nutritious product prepared by the mother.

These processes of local adaptation/reinterpretation of globalized products have been analyzed in the emblematic case of pizza.

Systems that coexist

The evolution of food systems linked to urbanization cannot be interpreted simply as a shift from domestic and artisanal systems to industrial systems.

These systems coexist and combine. They offer resources to address the multiple food challenges facing these cities, which often experience rapid population growth. Often forged under severe constraints, in urban contexts characterized by resourcefulness and mobility, these resources are tools for adapting to situations of hardship and uncertainty. Rather than imagining solutions that come from outside and from technology, it is possible to draw on this treasure trove to promote practices and standards that favor social and economic justice, peaceful coexistence between cultural differences, health, and the environment.

This article draws on the authors' work and their recently published collective work Manger en ville, Regards socio-anthropologiques d'Afrique, d'Amérique latine et d'Asie (Eating in the City: Socio-anthropological Perspectives from Africa, Latin America, and Asia), published by Quae, which brings together contributions from researchers from these three continents..![]()

Audrey Soula, Anthropologist, CIRAD, UMR Moisa, University of Montpellier; Nicolas Bricas, Socio-economist, researcher at Montpellier University, CIRAD, and holder of the UNESCO Chair in World Food Systems, CIRAD and Olivier Lepiller, Sociologist, researcher at CIRAD, UMR Moisa, University of Montpellier, CIRAD

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.