Clean water thanks to the sun

The contamination of water resources by organic micropollutants is a growing global concern, posing significant challenges for water quality and human health.

Gael Plantard, University of Perpignan and Julie Mendret, University of Montpellier

These organic micropollutants, such as pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and persistent organic compounds, are often detected in minute concentrations in water (micrograms or even nanograms per liter), but even at these concentrations, their impact on aquatic ecosystems and public health is proven.

Global warming exacerbates the situation, as temperature variations, changes in hydrological regimes, and extreme weather events can affect the mobility of these substances and lead to an increase in their concentration in water reservoirs.

Conventional wastewater treatment technologies used in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) may be insufficient to remove these substances. Treatment plants therefore contribute to the dispersion of these substances into the environment.

Faced with this reality, it is becoming imperative to develop new water treatment processes capable of effectively removing organic micropollutants. Innovative approaches—for example, the use of advanced oxidation technologies (AOTs), activated carbon adsorption, or membrane separation—are needed to meet the growing challenge of micropollutant contamination.

Advanced oxidation technologies

Ozone treatment processes (OTPs), such as ozonation and photo-oxidation processes, have the advantage of non-selectively destroying organic contaminants, whether biotic (bacteria, pathogens) or abiotic (pesticides, pharmaceuticals), and are therefore ideal for addressing the issue of micropollutants.

They involve producing extremely reactive chemical species (called "radicals" or "hydroxyl radicals"), which are capable of breaking the carbon-carbon bonds that make up various organic substances. This process leads to the degradation of pollutants into carbon dioxide, water, and salts: this is known as mineralization.

Among TOAs, some processes convert light energy into chemical energy to oxidize and degrade organic molecules—these are known as photo-oxidative processes. In the case of heterogeneous photocatalysis, photons are captured by a photosensitive material such as photocatalysts (titanium dioxide or zinc oxide, for example). They induce the formation of charges on the surface of the catalyst, which initiate the production of radical species via redox processes.

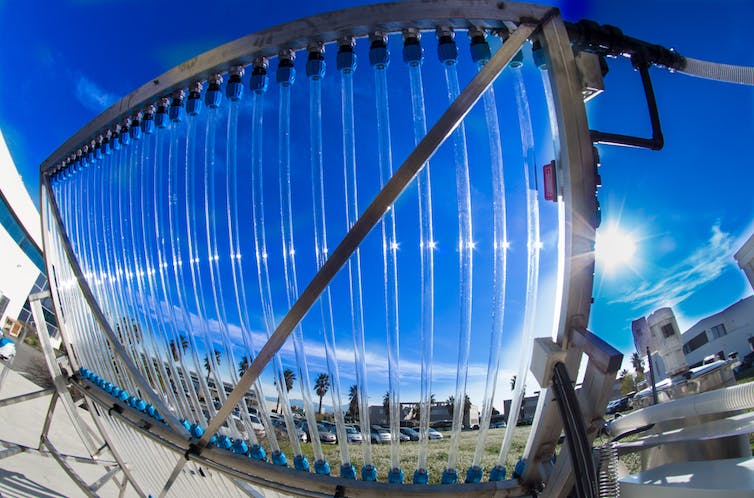

Photo-oxidation technologies should make it possible to use sunlight to break down contaminants. Solar photoreactor-type facilities are still being developed in laboratories. The aim is to optimize yields and also to see how to achieve the lowest possible environmental and energy costs (during operation).

For example, research has been conducted to evaluate the capabilities of solar photoreactors for decontaminating wastewater from hospitals (pharmaceutical products), agricultural effluents (biocide residues), groundwater remediation (solvent residues such as trichloroethylene), and wastewater treatment for agricultural (irrigation) or industrial uses.

To consider deploying these technologies, it is necessary to increase the performance of solar photoreactors and optimize the use of solar resources.

The solar resource available for photo-oxidation

The use of solar energy is a major challenge in the current global climate, energy, and environmental context in order to ensure the energy transition. To this end, efforts are being made to implement sustainable, low-energy-cost technologies that operate using solar energy.

This solar resource is variable (due to clouds, the alternation between day and night, and the seasons, etc.). When seeking to generate electricity (photovoltaic), this is a pitfall, as it is costly to store the electricity generated until it is needed.

On the other hand, for water treatment, contaminants can be stored by adsorption on carbon columns or in wastewater retention basins, waiting for the sun to shine.

Thus, in order to develop solar-powered water purification facilities, their operating capacity is designed on an annual basis, or their capacity is optimized to meet specific needs—seasonal needs, for example, in tourist areas.

Finally, solar radiation is divided into three main wavelength families: ultraviolet, visible, and infrared radiation. The photocatalysts currently available on the market have limitations in terms of solar spectrum absorption. Today, only the ultraviolet range—which represents only 5% of the solar spectrum—can be used for photocatalysis applied to water treatment.

For three decades, studies have been conducted to improve the performance of photosensitive materials, with the aim of increasing photo-conversion efficiencies and their ability to absorb visible radiation (45% of the solar spectrum).

In this context, the challenges now lie in strengthening the capacities of existing sectors, improving water quality, and reducing the energy costs of facilities.

To this end, the future of advanced oxidation technologies lies in combining them with other processes: biological processes (to eliminate "bioresistant" pollutants, i.e., those that are not biologically degradable), membrane processes (to eliminate small pollutants that are not filtered by membranes), or even the solar thermodynamic cycle (to thermally activate catalysts).

The Aquireuse Project

Our Aquireuse project explores a treatment process that is unique in France, based on an initial stage of solar photocatalysis, followed by infiltration into soil rich in organic matter, which helps to break down pollution.

Indeed, for certain uses, such as recharging treated wastewater from groundwater that will serve as a reserve for drinking water production, the water must be free of micropollutants.

Recharging groundwater with treated wastewater is a practice that is still unknown in France but is more widespread in places such as Australia and California. In particular, it helps combat a phenomenon that is becoming increasingly common in coastal areas, known as "saltwater intrusion." When the level of groundwater along the coastline drops due to excessive withdrawal, seawater seeps in and contaminates freshwater resources, as the saltwater becomes unfit for human consumption.

In the Aquireuse project, effluent from a WWTP is used to feed a pilot solar photocatalysis device where the first stage of total or partial degradation of micropollutants takes place. The treated effluent is then sent for infiltration into sediments, where the organic matter in the soil contributes to refining the treatment by continuing the degradation of micropollutants and by-products from solar photocatalysis.

The initial results are very promising: a large proportion of micropollutants are completely degraded after passing through the treatment process. These results are currently being published.

Such a process, combining a sustainable method with a nature-based solution, is an example of the circular economy in water treatment.

Gael Plantard, University Professor of Materials Chemistry, University of Perpignan and Julie Mendret, Senior Lecturer, HDR, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.