New structures identified within our chromosomes

Since the beginning of this century, major technological advances in molecular and genomic research, coupled with new approaches in very high-resolution photonic microscopy, have revealed new chromosomal structures and new principles of organization of our genomes (the genome contains all genetic information and therefore all DNA sequences transmitted through cell division).

Frédéric Bantignies, University of Montpellier and Giacomo Cavalli, University of Montpellier

This knowledge is crucial to understanding how our cells function, but also to better understand certain diseases and their progression.

Deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, contains genetic information specific to each living species. Chromosomes are the physical carriers of this information. The entire set of chromosomes is also called the genome and contains all the genes. Since the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA in 1953, the question of its organization within the nuclei of our cells has been the subject of extensive research worldwide. To fully understand this question, it should be noted that humans have 46 chromosomes, which contain 3 billion base pairs (bp) of DNA, representing a molecular filament approximately 2 m long. This strand can be contained within cell nuclei measuring approximately 10 μm (one micrometer = one thousandth of a millimeter) in diameter. To better understand how the genome and our genes function, it was therefore essential to know how all this DNA is able to fold into a cell nucleus.

At the beginning of this organization, we have the nucleosome, whose structure was elucidated in 1997. The nucleosome is formed of highly basic proteins called histones, which have a high affinity for the acidic DNA molecule. These histones form a central body around which the DNA molecule winds, at a rate of 146 bp per nucleosome, forming a sort of "macaron" 11 nm (one nanometer = one millionth of a millimeter) wide and 6 nm high. The nucleosome therefore represents the first structural level of DNA organization in the nucleus. As a sign of its importance, this very particular structure is found in all organisms with nuclei (eukaryotes), whether they are single-celled or more complex, such as animals and plants.

For a very long time, it was thought that the succession of nucleosomes (also called chromatin fibers), forming a kind of "string of pearls," wound around itself in a regular manner to form a fiber 30 nm in diameter. Spiral supercoils of this fiber were thought to ultimately lead to chromosomes. However, technical limitations, including the low resolution of microscopy techniques and the lack of other methods, made it impossible to prove whether this hypothesis was correct.

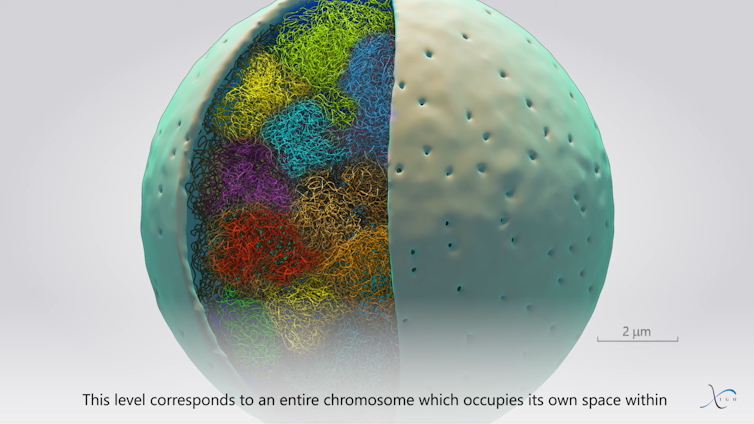

On the other hand, we have known since 1985 that the organization of chromosomes in cell nuclei is not random. Furthermore, the well-known X-shaped form of chromosomes is not incorrect, but represents only a very transient stage in their organization. This highly condensed X-shaped conformation is conducive to their segregation (sharing) in daughter cells during cell division. But the rest of the time, the shape of chromosomes is quite different. Visualization using fluorescent molecules capable of specifically interlocking with the DNA double helix has shown that each chromosome occupies its own territory within the nucleus, thus avoiding excessive entanglement with other chromosomes. This property of "chromosomal territory" is also found in most species and appears to be very important, particularly for species with a large number of chromosomes.

New technologies provide a fresh perspective on genome organization

At the beginning of the 21st century, numerous studies around the world have led to a better understanding of the different levels of structural organization of the genome between the nucleosome and chromosomal territories.

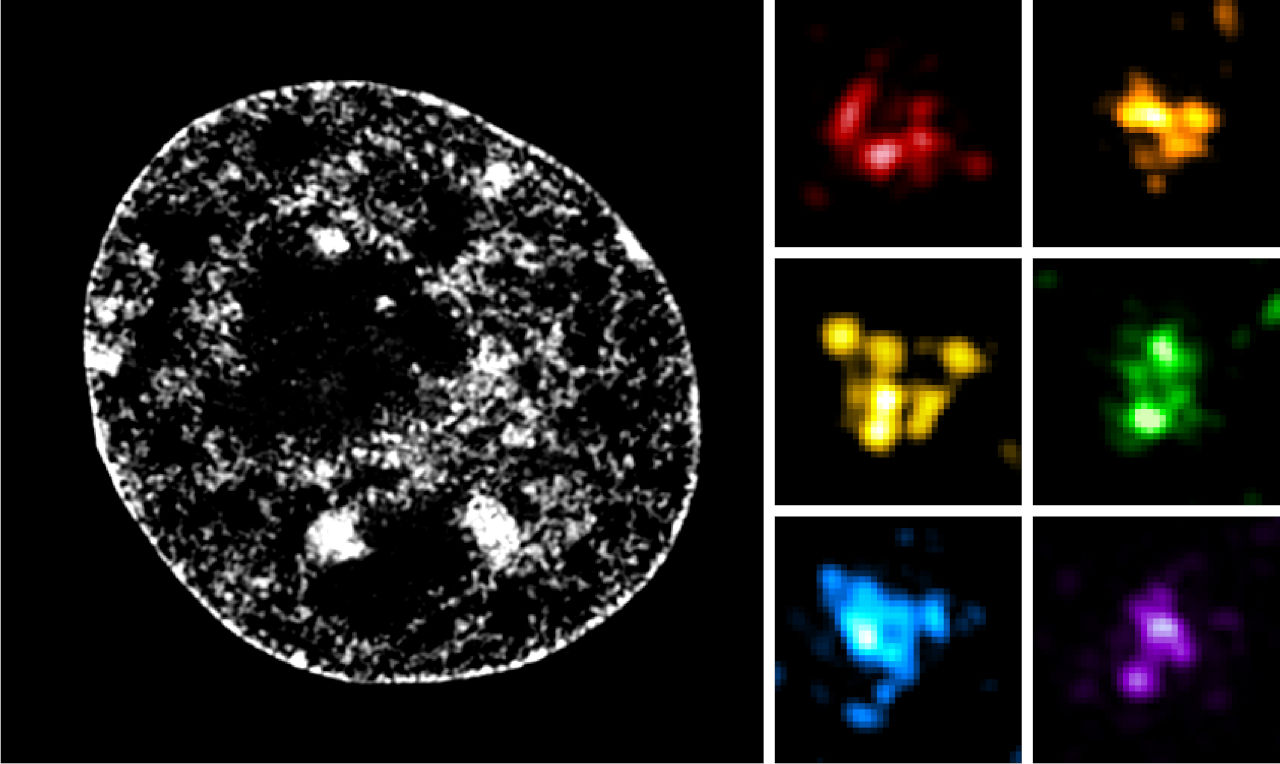

These advances were made possible by the development and use of brand new technologies. First, there were new genomics techniques, including very high-throughput DNA sequencing (next-generation sequencing) and the ability to capture fine chromosome structures molecularly using the "Hi-C" method. At the same time, the advent of super-resolution photonic microscopy, which uses fluorescent DNA markers, made it possible to visualize these chromosomal structures directly in the cell nucleus.

Frédéric Bantignies, Giacomo Cavalli, Provided by the author

Let's return to our scale of chromosome organization. The first level is the nucleosome. A second level of organization corresponds to groups of several nucleosomes, like small clusters called "nucleosome clutches" (named by the authors who discovered them in analogy to eggs found in brooding nests). Nucleosomes are therefore not grouped in a regular manner as previously thought, but rather in irregular clusters.

These "nucleosome clutches" then group together to form a structure called a "chromatin nanodomain, " or CND, which includes approximately 100,000 to 200,000 DNA base pairs, forming large irregular clusters of nucleosomes 150 to 300 nm wide. These two levels were discovered recently (in 2015 and 2020, respectively), thanks to super-resolution microscopy, which is capable of resolving structures measuring 20 to 100 nm.

TADs structure the genome and regulate gene expression.

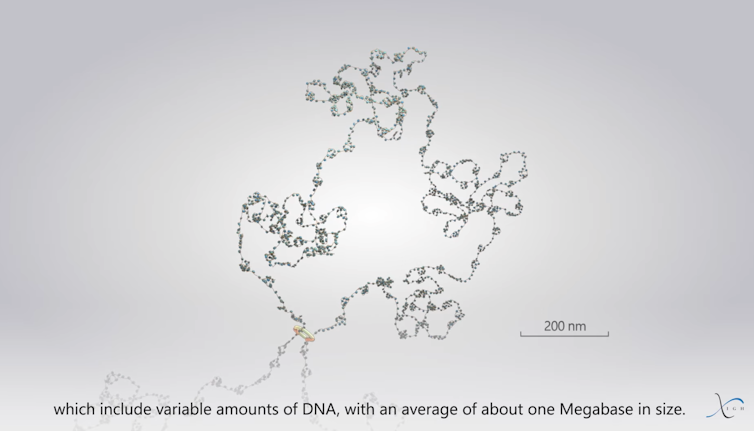

The next level of this organization is called TAD, or Topologically Associating Domain, identified in 2012 using the Hi-C molecular method. TADs are composed of several CNDs, forming super clusters of nucleosomes approximately 500 nm wide. They thus comprise variable sizes of DNA, with an average of approximately 1 megabase (1 million base pairs). Our laboratory contributed to the discovery of CNDs and TADs.

Frédéric Bantignies, Giacomo Cavalli, Provided by the author

TADs are fairly heterogeneous structures, mainly due to their dynamic formation mechanism. This mechanism involves the passage of the famous "string of pearls" (referring to the succession of nucleosomes) through the ring formed by cohesin. The chromatin fiber continues to pass through the ring until it encounters nuclear factors called CTCF at the boundaries of a TAD. These factors act as a kind of "customs officer," stationed on the DNA to block the fiber's progress. As the fiber passes through, the nucleosomes will organize themselves into clutches and CNDs. The TAD then represents the entire large loop of chromatin that has passed through the cohesin ring.

Within chromosomes, gene activity is influenced by a whole host of regulatory sequences (a kind of switch) that can be located tens of thousands of base pairs away from their gene. TADs therefore preserve genes and their regulatory regions in the same molecular environment, which can promote their expression (i.e., their reading to lead to protein production) in a given cell type where their activity is necessary. Thanks to their boundaries, they also allow genes to be clearly separated from each other, preventing active genes from influencing other inactive genes in a given cell type.

Recent studies have shown that chromosomal defects at the boundaries of TADs (such as inversions or deletions that affect the positioning of CTCF or render it inoperative) lead to defects in gene isolation and, consequently, to erroneous gene activation. In some cases, these rearrangements activate genes called "proto-oncogenes," which can cause cells to transform and lead to the development of tumors.

Compartmentalization and territorialization of the genome

Frédéric Bantignies, Giacomo Cavalli, Provided by the author

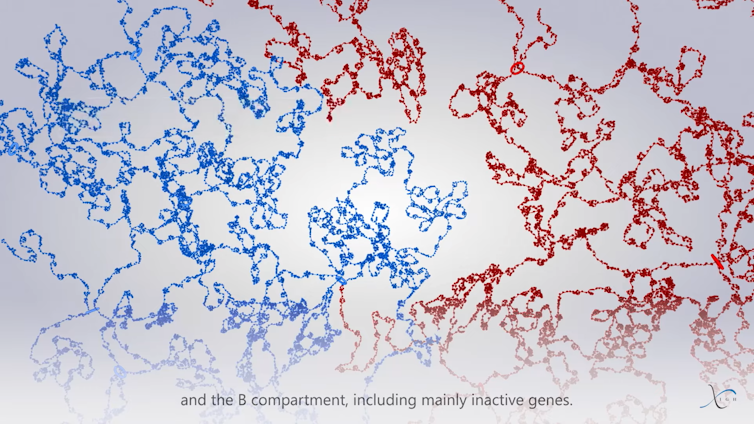

Several TADs then group together into two distinct compartments: compartment "A," which mainly contains active genes, and compartment "B," which mainly includes inactive genes. This grouping into compartments helps to strengthen the functions of the genome.

Frédéric Bantignies, Giacomo Cavalli, Provided by the author

Finally, at the end of this organizational scale, we find chromosomal territories, which allow chromosomes to be individualized from one another within the nuclei. This organization plays an important role in DNA replication (identical copying of genetic material) and cell division, where each duplicated chromosome is split in two in the daughter cells.

And so we come full circle! Well, almost: the next step is to gain a better understanding of how this organization influences the various molecular processes inherent in the genome, which regulate gene expression, DNA replication, DNA repair in the event of damage or stress, and DNA recombination, particularly in reproductive cells. The field of investigation remains vast, but a better understanding of the organization of the genome will pave the way for a better understanding of all these nuclear processes in normal cells, but also, of course, in cells with chromosomal defects that lead to diseases such as cancer.![]()

Frédéric Bantignies, Director of Research , University of Montpellier and Giacomo Cavalli, Director of Research at CNRS, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.