Cutting-edge technologies serving underwater archaeology

Who would believe that the scarcity of fish poses a threat to the approximately three million shipwrecks scattered across the world's seabeds?

Vincent Creuze, University of Montpellier

However, industrial trawling, often carried out at depths of over 1,000 meters and now partially limited to 800 meters in Europe, is one of the main threats to the submerged heritage of the deep sea. In a matter of seconds, a site that is thousands of years old can be disrupted or even destroyed, even though it has been remarkably well preserved until now, thanks in particular to the darkness and low temperatures, far from violent tidal currents and surface weather phenomena.

The remarkable state of preservation of deep-sea wrecks makes them of major archaeological interest, but unfortunately also attracts the attention of a few private "treasure hunting" companies, which recover the cargoes to resell them, without any concern for archaeological study and often in violation of the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage.

Preserving underwater heritage

Faced with these threats, countries must urgently locate and assess their underwater cultural heritage in order to preserve its invaluable scientific and cultural value. In recent years, underwater archaeology services in many countries have begun exploring the depths of the ocean.

France, the world's second largest maritime area, has a special position in this race. In 1966, André Malraux, then Minister of Culture, created the DRASSM, the Department of Underwater and Underwater Archaeological Research. For more than 50 years, French underwater archaeologists have honed their expertise and know-how, which are now recognized worldwide. Until recently, most archaeological campaigns were limited to human diving, with a few occasional forays into deeper waters as part of oceanographic (Ifremer) or industrial (Comex, in particular) operations.

DRASSM, 2019

Since the 2010s, given the urgency of protecting deep-sea heritage, underwater archaeologist Michel L'Hour, Director of DRASSM, has launched an ambitious program to develop innovative tools dedicated to deep-sea archaeology. The first phase consisted of designing a vessel suitable not only for human archaeological excavations at depths of between 5 and 50 meters, but also for deploying robots to survey wrecks at depths of over 1,000 meters. This 36-meter vessel was launched in 2012 and is aptly namedAndré Malraux.

Wreck detection

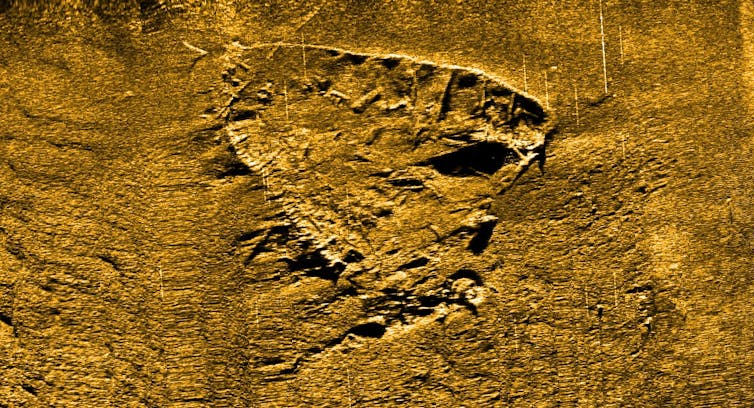

When it comes to detecting wrecks, electromagnetic waves hardly penetrate the sea at all, so most technologies rely on the use of acoustic waves. This is the case, for example, withsidescan sonar, an acoustic antenna towed a few meters above the seabed. It is used to map the seabed and detect anomalies in the relief. When mapping depths greater than 300 or 400 meters, sidescan sonar is installed on an autonomous robot called an AUV (Autonomous Underwater Vehicle). Sidescan sonar is often combined with a magnetometer, which detects magnetic anomalies, possibly caused by the metal masses of a wreck.

DRASSM

These operations, known as "surveys," are carried out either as part of preventive archaeological operations (for example, prior to the laying of an underwater cable) or as part of the search for specific shipwrecks. For example, the wrecks of the Cordelière and the Regent, which have been lying at the mouth of the Brest channel since 1512, are currently the subject of an extensive search campaign. For this type of clearly identified wreck, the search areas are narrowed down by a meticulous study of archives (accounts of witnesses or survivors, meteorological archives, studies of sea currents, morphogeology, old nautical charts, newspapers of the period, etc.), but also by analysis of oceanographic data such as currents, tides, and prevailing winds.

The assessment phase

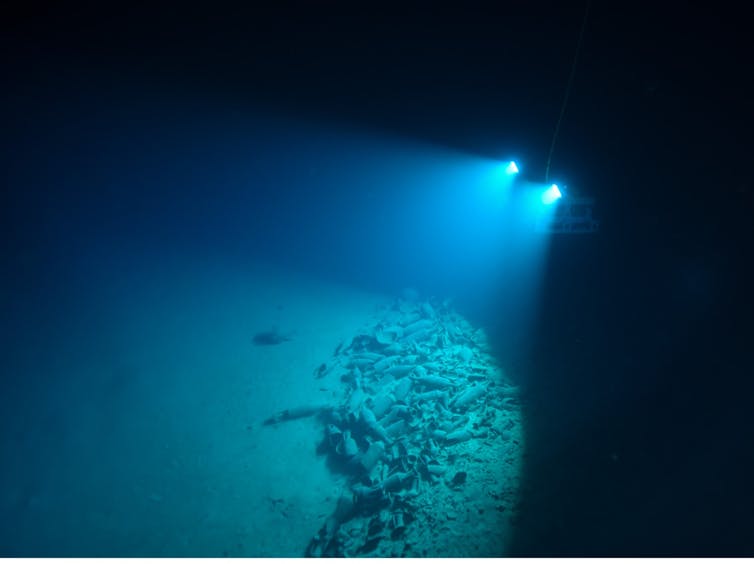

The survey is followed by an inspection, which allows for a visual determination of whether the magnetic or acoustic anomalies correspond to shipwrecks. Beyond the limits of human diving, this inspection is most often carried out by aremotely operated vehicle (ROV). Thanks to its umbilical cable connecting it to the surface, the ROV transmits live video footage to the pilot on board the ship stationed above the wreck.

F. Osada/DRASSM

If the site is interesting, hundreds or even thousands of photos are taken to build a 3D model of the wreck afterwards. This technique, known as photogrammetry, is now perfectly mastered. It is used both with an SLR camera (Ifremer, ipso facto) and by coupling several digital cameras (Comex). The models are then used for scientific purposes or made available to the general public for virtual reality tours, as DRASSM did for the wreck of the Lune and the battleship Danton, which has been lying at a depth of 1,025 meters since 1917.

In 2019,Onera (French National Aerospace Research Agency), LIRMM (Montpellier Robotics and Microelectronics Laboratory), and DRASSM designed a new single-camera system, the size of a water bottle, capable of producing a real-time 3D model while accurately calculating the robot's position. This technology facilitates navigation and speeds up the interpretation of the sites visited.

Take without breaking

When examining a shipwreck, it is sometimes necessary to take samples. Existing ROVs were developed mainly for the oil industry and are unsuitable for archaeological work. The slowness and lack of dexterity of their hydraulic manipulator arms force pilots to place the robots on the seabed, i.e. on the wreck itself. Furthermore, the hydraulic grippers on the arms are often incompatible with the fragility and shape of the most delicate archaeological objects (glass, wood, leather, rope, fabric, etc.). For these reasons, since 2012, DRASSM has been developing specialized robotic tools with the support of LIRMM.

A laboratory site 91 meters underground

Louvre: Department of Graphic Arts: inv. 32594

Most of the tests for this program are conducted near Toulon, on the legendary wreck of the Lune, at a depth of 91 meters. This ship, which belonged to Louis XIV and sank in 1664, presents most of the challenges encountered on deep-sea wrecks and allows new robotic tools to be tested after they have been validated in the laboratory.

Thus, in 2014, archaeological samples were taken using a robotic hand designed by Techno Concept (Loupian, Hérault), followed by a claw.

Thanks to a computer-assisted control algorithm developed at LIRMM, the carrier robot achieves horizontal and vertical precision of around 1 to 2 cm, which means that manipulator arms are no longer needed and it can work "on the fly" without touching the bottom. The robot pivots and moves directly to gently bring the claw or hand to the object to be picked up. The absence of arms significantly reduces the size of the robots, allowing them to access cramped or complex areas of wrecks more easily.

F. Osada, T. Seguin/DRASSM

Encouraged by these initial results, French archaeologists expanded their collaborations. In 2016, the underwater humanoid Ocean One, developed entirely by Professor Oussama Khatib's team at Stanford University, made its first dive to the wreck of the Lune, accompanied by DRASSM and LIRMM. The robot has two innovative arms, powered quickly and precisely by electric motors and equipped with force sensors. The forces are reproduced using haptic interfaces, a kind of motorized joystick that allows the robot to be controlled in translation and rotation, similar to those used to control surgical robots.

Still in the field of manipulation, this time as part of the ANR SeaHand project,the PPrime Institute finalized a robotic hand specifically designed for underwater archaeology in early 2020. By measuring the forces perceived by each finger, the SeaHand opens the way to "touch" excavation in turbid environments. This was unthinkable just a few years ago.

All these advances meet many of the needs of deep archaeology, but there are still many challenges to be overcome, such as the delicate removal of large volumes of sediment during a methodical excavation or the automatic analysis of the large amounts of data generated during survey operations.![]()

Vincent Creuze, Associate Professor in Underwater Robotics, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.