From Lavisse to Bescherelle, these textbooks have left their mark on generations of students.

Lavisse, Bled, Bescherelle, Lagarde, and Michard are names that remain irrevocably linked to the history, conjugation, spelling, and literature textbooks authored by these teachers. Their works left their mark on the history of education inthe 19th and20th centuries, becoming part of the standard repertoire of reference materials for students.

Sylvain Wagnon, University of Montpellier

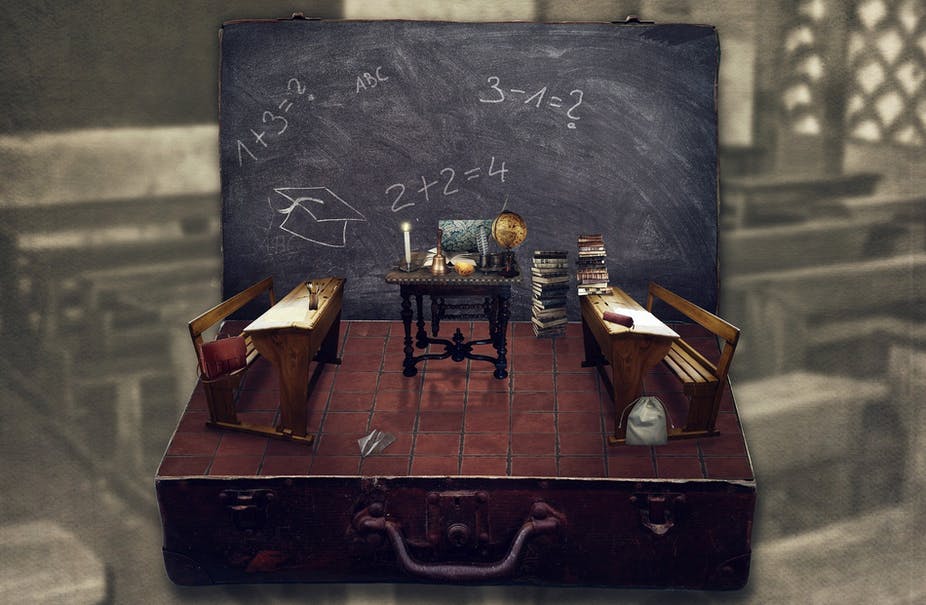

DarkWorkX/Pixabay, CC BY

How can this longevity be explained? How did these textbooks become symbols of a certain school culture? What do they reveal about the organization of the French education system and teaching methods to this day?

As witnesses to their time and objects of research, textbooks must be approached holistically. A pioneer in their study, Alain Choppin clearly demonstrated that textbooks were a historical falsehood, covering a diversity of formats and uses. As tools for implementing curricula and links between institutions, teachers, students, and parents, textbooks are pillars of the development of a school culture, to use André Chervel's term, derived from encyclopedic academic knowledge.

Their content is sometimes criticized for its bias. Due to their impossible neutrality, they have conveyed gender and class stereotypes, both in the past and today. Even though their demise is often predicted in the face of the expansion of online resources, they are still here, in paper or digital form. The recent lockdown period has only confirmed this state of affairs with the free provision of digital textbooks in the name of educational continuity.

School novels

Ernest Lavisse (1842–1922) was one of the most prolific and widely published authors of Armand Colin, with over 20 million copies sold for all levels of education. A renowned historian, he developed a "national narrative" based on a school history centered on France, its power, and its mythical male figures.

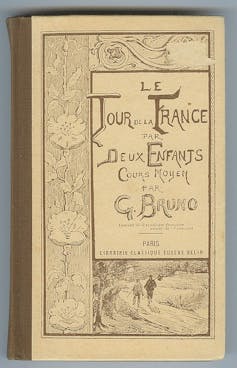

Jean Poussin/Wikimedia, CC BY

In the same vein, Le tour de France par deux enfants (A Tour of France by Two Children) by Augustine Fouillée, writing under the pseudonym G. Bruno, first published in 1877, reflects this same concept of the textbook and model lesson: an encyclopedic narrative that allows the teacher to be the linchpin of knowledge transmission and to develop a patriotic discourse in post-war France in 1870 and during the construction of the republic.

What are commonly referred to as "the little Lavisses" remained the standard history textbooks until World War II. Today, of course, developments in the discipline and in teaching methods, which now focus on document-based analysis, have rendered Lavisse a relic of ancient history. Nevertheless, these works continue to be republished to this day as references to an ancient and nostalgic history.

French language and literature

While Ernest Lavisse, an academic, writes for teachers and students based on his understanding of history, Odette and Édouard Bled, schoolteachers, design their spelling and grammar textbook based on their observations in the field. An essential resource for generations of schoolchildren since its first edition in 1946, the Bled is often associated with the "Bescherelle," a verb conjugation manual.

Supported by educational institutions, these two works are still perceived as "official" works, essential to schooling. Nevertheless, they reflect a certain vision of education. Édouard Bled was a fierce opponent of any spelling reform, and Bescherelle, based exclusively on rote learning, does not take into account the evolution of teaching towards context awareness or text analysis.

Bordas editions

High school teachers, then inspectors general, André Lagarde and Laurent Michard published a series of textbooks starting in 1948, consisting of excerpts from literary references, illustrations, and biographies. Their first publication marked a revolution in publishing. In six volumes, they presented a chronological anthology of French literature.

Today, Lagarde and Michard appear more as symbols of secondary education based on encyclopedic knowledge. On the other hand, in terms of content, the choice of certain text excerpts and commentaries is subject to criticism. Nevertheless, these books, which have also sold over 20 million copies, remain references for certain teachers and, above all, in the memories of several generations of high school students.

Exchange tool

One might therefore legitimately question the longevity of these works. Is this due to their extraordinary ability to reinvent themselves, or is it symptomatic of a certain pedagogical inertia? At the beginning ofthe 20th century, progressive educators such as Célestin Freinet criticized this reliance on textbooks, arguing that they prevented students from thinking for themselves.

Since the 1960s, textbooks have no longer been written by individual authors but by teams. No single textbook has a monopoly anymore, and multiple publishing houses compete ingeniously to offer textbooks with high-quality illustrations and documents that take into account evolving teaching methods. It should be noted that school books account for between 12% and 18% of French publishing revenue.

Secondly, the use of textbooks in classrooms is a complex issue. They serve as a reference and a support for teachers in imparting knowledge, but also as a means of communicating the curriculum to parents, as the lockdown period clearly demonstrated.

See also:

Distance learning: lessons learned from e-lockdown

To date, the use of textbooks has also led to a specific culture and form of schooling, where teachers and the knowledge they impart are at the heart of the institution. For now, the digital revolution seems to have had little impact. Perceived as the preferred tools of apprenticeshipsTextbooks must also serve as tools for understanding the changes in our societies and as vehicles for transforming our ways of seeing.![]()

Sylvain Wagnon, Professor of Education Sciences, Faculty of Education, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.