In France, mosquitoes also transmit the Usutu virus.

The events took place two years ago, but scientists have only just discovered that this was the first case of human infection with the Usutu virus in France. On November 10, 2016, a 39-year-old man was hospitalized for three days in the neurology department at Montpellier University Hospital for sudden paralysis of half of his face.

Yannick Simonin, University of Montpellier

The patient recovered all his faculties within a few weeks, with no lasting effects. Subsequent tests showed that he had been infected with this virus.

It was the work carried out by our team of biologists from the University of Montpellier, Inserm, and Montpellier University Hospital that enabled us to understand the origin of this man's symptoms. We analyzed 666 cerebrospinal fluid samples taken from patients hospitalized in 2016 in Montpellier and Nîmes, as explained inthe article we have just published in the journal Infectious Emerging Diseases. Only one sample revealed the presence of the Usutu virus: his.

The most likely scenario is that this man was infected by a mosquito after it bit a bird, which is a reservoir for this virus. Transmitted to humans mainly by the Culex mosquito, which is common in France, this virus has been circulating in our country since at least 2015, according to a study by the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (ANSES). Along with chikungunya, dengue, and West Nile, Usutu is now one of the mosquito-borne viruses that has caused at least one indigenous case in France—that is, in a person who has not traveled abroad. While Usutu is not the most dangerous of these viruses that the French must learn to live with, it nevertheless deserves the attention of scientists and health authorities.

A name taken from a river in Swaziland, Africa

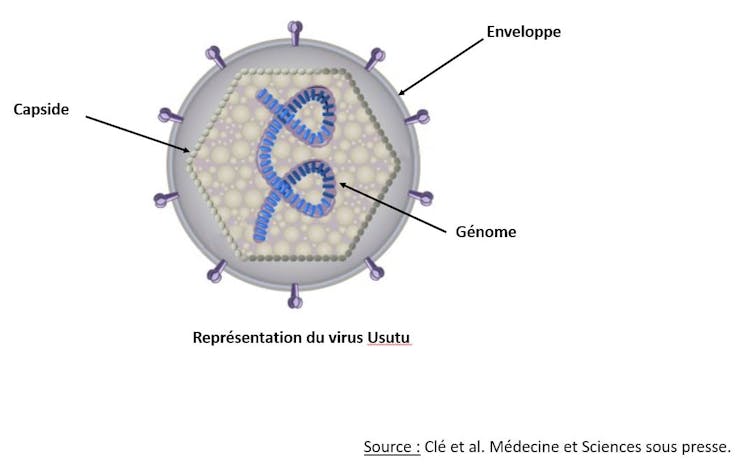

The Usutu virus was virtually unknown until recently. It has attracted the attention of the scientific community due to its widespread propagation in Europe. Usutu is an arbovirus belonging to the Flaviviridae family and the flavivirus genus, which comprises more than 70 members.

Clé et al. Medicine and Science in Press.

Among these are some of the most dangerous arboviruses for humans, such as the Zika virus, dengue fever, yellow fever, and West Nile fever. Usutu was named after the river of the same name located in Swaziland, a small African country bordering South Africa. It was first identified there in 1959.

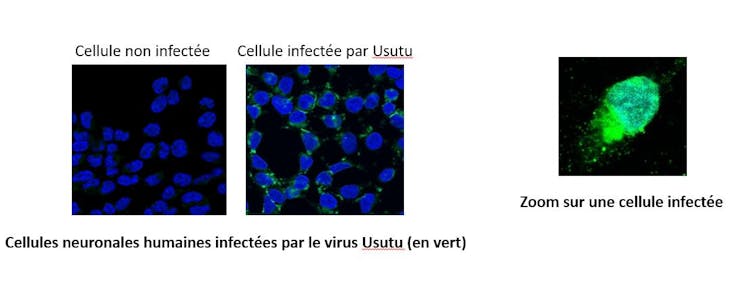

Little is known about Usutu's target cells. However, our team recently described its ability, like other flaviviruses, to infect cells of the nervous system in vitro (in the laboratory).

Salinas et al., PLoS Negl Trop Dis., 2017 Sep 5;11(9):e0005913.

Birds as hosts, mosquitoes as vectors

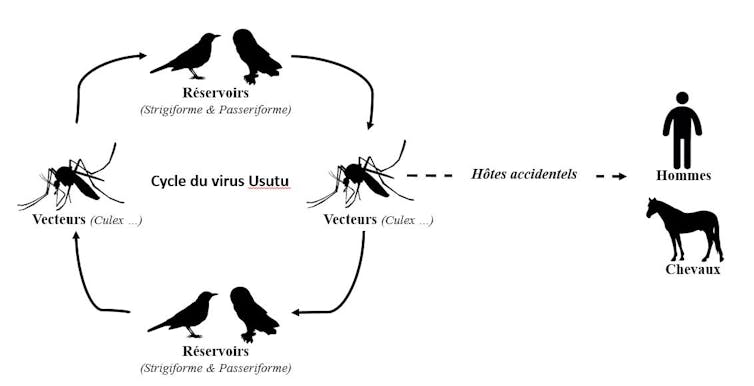

The natural transmission cycle of Usutu is enzootic, meaning it is localized to a given area. It mainly involves passerine birds (e.g., blackbirds or magpies) and strigiform birds (e.g., great grey owls) as "amplifier" hosts, i.e., hosts that allow the virus to actively multiply. Ornithophilic mosquitoes (mosquitoes that bite birds) serve as vectors for transmission to humans.

Clé et al. Medicine and Science in press.

Various studies have demonstrated the involvement of several mosquito species in maintaining the Usutu cycle within the avifauna, i.e., birds occupying the same location. The virus has thus been isolated in Aedes albopictus mosquitoes (better known as tiger mosquitoes), Aedes caspiuis, Anopheles maculipennis, Culex quinquefasciatus, Culex perexiguus, Culex perfuscus, Coquillettidia aurites, Mansonia Africana, and Culex pipiens. These different species are ornithophilic but also bite humans.

Mosquitoes transmit the virus to humans, as well as to horses. These species are susceptible to Usutu but are considered accidental hosts and epidemiological "dead ends"—meaning they cannot transmit the virus to other members of their species.

High mortality among birds

Usutu has also been found in many species of birds. Several migratory species are believed to be responsible for introducing Usutu to Europe, while others are believed to be responsible for its spread. Among those susceptible to Usutu infection, blackbirds ( Turdus merula ) have the highest mortality rate.

Central nervous system disorders have been reported in birds infected with Usutu. These birds show signs of prostration, disorientation, motor incoordination, and weight loss. Autopsies frequently reveal inflammation of the liver (hepatomegaly) and spleen (splenomegaly).

Lesions have also been reported in the heart, liver, kidneys, spleen, and brain of infected birds. These observations show that Usutu can be highly pathogenic in birds due to its replication and virulence in a large number of tissues and organs. Usutu thus causes significant bird mortality in different regions of Europe.

A virus first discovered in Europe in 2001

The virus was first detected in Europe in 2001, in Austria, in dead birds. It was then reported in many European countries, in mosquitoes or birds.

In 2015, France also detected this virus in common blackbirds, following an increase in their mortality in the Haut-Rhin and Rhône departments, analyzed by ANSES and the National Office for Hunting and Wildlife (ONCFS).

Furthermore, it has since been established that Usutu has been circulating among Culex pipiens mosquitoes in the Camargue since at least 2015. During the summer of 2016, a major Usutu epizootic affecting birds was again recorded in Europe, with widespread virus activity in Belgium, Germany, France, and for the first time in the Netherlands. This phenomenon highlights the continued geographical spread of Usutu, but also the emergence of new ecological niches.

The recurrence of Usutu infection in various European countries suggests a persistent transmission cycle in the affected areas, either through overwintering mosquitoes (the cold slows down their metabolism and they remain inactive until spring) or through multiple reintroduction of the virus by migratory birds from Africa.

Symptoms to be better characterized

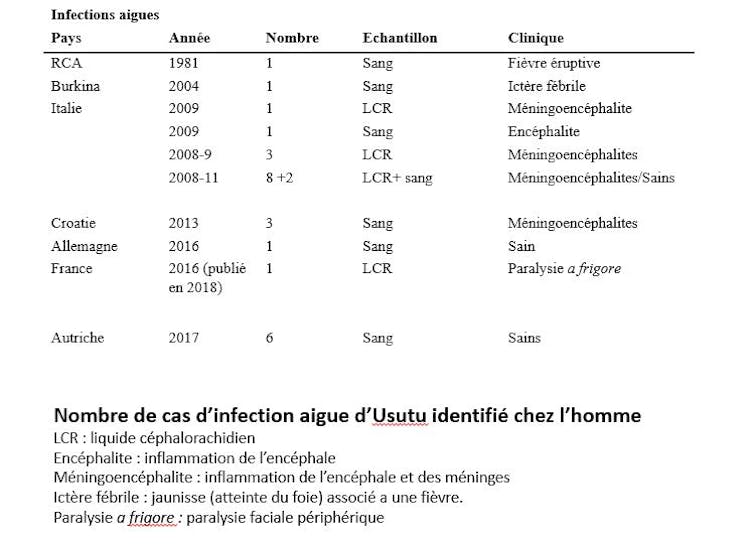

The risk of transmission from animals to humans associated with Usutu was first described in Africa. The first human case was reported in the Central African Republic in the 1980s, and the second in Burkina Faso in 2004. In both cases, the symptoms were moderate, including a rash and mild liver damage.

In Europe, there have been 28 cases of acute human infection with Usutu to date, mainly in Italy. In addition, more than 70 people with antibodies to this virus have been identified, demonstrating that these individuals have been exposed to the pathogen. Human infection is probably most often asymptomatic or presents with mild clinical symptoms. However, neurological complications such as encephalitis (inflammation of the brain, the part of the brain housed in the skull) or meningoencephalitis (inflammation of the brain and meninges, the membranes that surround it) have been reported, with a total of around 15 cases in Europe.

Clé et al. Medicine and Science in Press.

Our team's description of the atypical presence of facial paralysis, which appeared in the first French case, suggests that the full range of symptoms of Usutu virus infections is not yet fully understood.

A virus whose range is expanding

The recent history of outbreaks of other arboviruses calls for the scientific community to be extremely vigilant with regard to the Usutu virus. Its range now extends to a large number of European countries. Epizootics causing bird mortality are frequent. Genetically very different strains are circulating at the same time. These are all warning signs.

Although too few in number, a few seroprevalence studies (presence of antibodies against the virus in the blood) support the hypothesis that humans are more exposed to the risk of infection by Usutu than previously thought.

![]() Knowledge about the pathophysiology of this emerging virus is currently very limited. Ongoing research aims in particular to better understand its biology and the mechanisms associated with neurological damage. Research is also being conducted, accompanied by surveillance measures and prevention should be implemented in France, in the areas most at risk.

Knowledge about the pathophysiology of this emerging virus is currently very limited. Ongoing research aims in particular to better understand its biology and the mechanisms associated with neurological damage. Research is also being conducted, accompanied by surveillance measures and prevention should be implemented in France, in the areas most at risk.

Yannick Simonin, Inserm researcher and lecturer in infectious disease control, University of Montpellier

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.