Between ethics and laws, who can govern artificial intelligence systems?

We have all begun to realize that the rapid development of AI is truly changing the world we live in. AI is no longer just a branch of computer science; it has escaped from research labs with the development of "AI systems," or "software that, for human-defined purposes, generates content, predictions, recommendations, or decisions that influence the environments with which they interact" (European Union definition).

Bernard Fallery, University of Montpellier

AI applications are everywhere, introducing new risks, including the manipulation of behavior. How can we control their use?

Pixabay,CC BY

The challenges of governing these AI systems—with all the nuances of ethics, control, regulation, and rulemaking – have become crucial, as their development is now in the hands of a few digital empires such as Gafa-Natu-Batx...which have become the masters of real societal choices on automation and the"rationalization"of the world.

The complex fabric intersecting AI, ethics, and law is thus constructed in power relations—and collusion—between states and tech giants. But citizen engagement is necessary to assert imperatives other than technologicalsolutionism, where "everything that can be connected will be connected and streamlined."

AN ETHICS OF AI? THE MAIN PRINCIPLES AT AN IMPASSE

Admittedly, the three majorethical principlesenable us to understand how a genuine bioethics has been developed since Hippocrates: the personal virtue of "critical prudence," or the rationality of rules that must be universal, or the evaluation of the consequences of our actions with regard to general happiness.

[More than 80,000 readers trust The Conversation newsletter to help them better understand the world's major issues.Subscribe today]

For AI systems, these guiding principles have also formed the basis for hundreds of ethics committees: the Holberton-Turing Oath,the Montreal Declaration,the Toronto Declaration, the UNESCO Program... and evenFacebook! But AI ethics charters have never yet led to any sanctions or even the slightest reprimand.

On the one hand, the race for digital innovations is essential to capitalism in order to overcome contradictions in profit accumulation, and it is essential to states in order to developalgorithmic governmentalityandunprecedented social control.

But on the other hand, AI systems are always both a cure and a poison (a pharmakon in Bernard Stiegler's sense) and therefore continually create different ethical situations that do not fall under principles but require "complex thinking"; a dialogic in Edgar Morin's sense, as shown bythe analysis of ethical conflicts surrounding the Health Data Hub health data platform.

A RIGHT TO AI? A CONSTRUCTION BETWEEN REGULATION AND LEGISLATION

Even if broad ethical principles will never be operational, it is through critical discussion of these principles that AI law can emerge. The law faces particular obstacles in this area, notablythe scientific instabilityof the definition of AI, the extraterritorial nature of digital technology, and the speed with which platforms developnew services.

In the development of AI law, we can seetwo parallel movements. On the one hand, regulation through simple guidelines or recommendations for the gradual legal integration of standards (from technology to law, suchas cybersecurity certification). On the other hand, there is genuine regulation through binding legislation (from positive law to technology, such as theGDPR regulationon personal data).

POWER RELATIONSHIPS... AND CONNIVANCE

Personal data is often described as a new and highly coveted black gold, as AI systems have a critical need for massive amounts of data to fuel statistical learning.

In 2018, the GDPR became a genuine European regulation governing this data, whichhad benefited from two major scandals: the NSA's Prims espionage program and the misuse of Facebook data by Cambridge Analytica. In 2020, the GDPR even enabled activist lawyer Max Schrems to haveall transfers of personal data to the United Statesinvalidated by the Court of Justice of the European Union. But there are still many instances of collusionbetween states and digital giants: Joe Biden and Ursula von der Leyen are constantly reorganizing these data transfers, which are contested bynew regulations.

The Gafa-Natu-Batx monopolies are currently steering the development of AI systems: they control possible futures through "predictive machines" and the manipulation ofattention, they impose the complementarity oftheir servicesand will soon integrate their systems intothe Internet of Things. Governments are reacting to this concentration of power.

In the United States, a lawsuit to force Facebookto sell Instagram and WhatsAppwill begin in 2023, and a change toantitrust legislationwill be voted on.

In Europe, starting in 2024, the Digital MarketsAct (DMA) will regulate acquisitions and prohibit "large gatekeepers" from self-referencing or bundling their various services. As for the Digital ServicesAct (DSA), it will require "big platforms" to be transparent about their algorithms and to quickly manage illegal content, and it will prohibit targeted advertising based on sensitive characteristics.

But collusion remains strong, as each country protects "its" giants by brandishing the Chinese threat. Thus, under pressure from the Trump administration, the French governmentsuspended payment of its "Gafa tax,"even though it had been approved by parliament in 2019, andtax negotiationscontinue within the framework of the OECD.

NEW AND ORIGINAL EUROPEAN REGULATION ON THE SPECIFIC RISKS OF AI SYSTEMS

Spectacular advances in pattern recognition (in images, text, voice, and location) are creating prediction systems that pose growing risks to health, safety, and fundamental rights: manipulation, discrimination, social control, autonomous weapons, etc. Following China's regulation on the transparency of recommendation algorithms in March 2022, the adoption ofthe AIA Act, the European regulation on artificial intelligence, will be a new milestone in 2023.

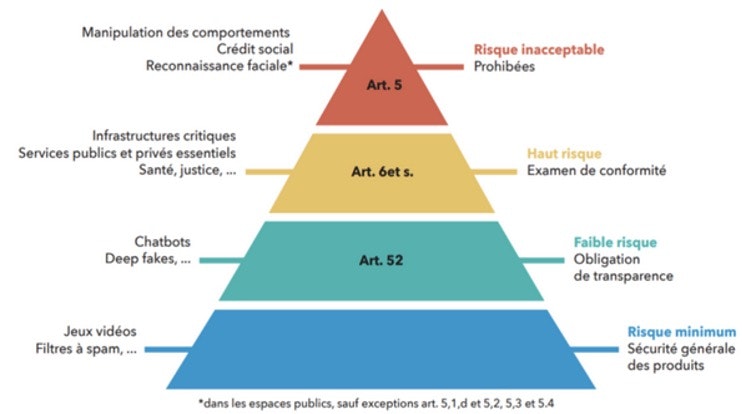

Yves Meneceur, 2021, Provided by the author

This original legislation is based on thedegree of riskposed by AI systems, using a pyramid approach similar to that used for nuclear risks: unacceptable, high risk, low risk, minimal risk. Each risk level is associated with prohibitions, obligations, or requirements, which arespecified in annexesand are still being negotiated betweenParliamentand theCommission. Compliance and sanctions will be monitored by the competent national authorities and the European Committee on Artificial Intelligence.

CITIZENS COMMITTED TO AN AI RIGHT

To those who consider citizen engagement in the development of AI law to be utopian, we can first point to the strategy of a movement such asAmnesty International: advancing international law(treaties, conventions, regulations, human rights tribunals) and then usingitin concrete situationssuch as the Pegasus spyware case or the ban on autonomous weapons.

Another successful example is the None of Your Business (it's none of your business):advancing European law(GDPR, Court of Justice of the European Union, etc.) by filinghundreds of complaintseach year against privacy violations by digital companies.

All these citizen groups, which are working to develop and utilize AI law, take a wide variety of forms and approaches. They range from Europeanconsumerassociations filing joint complaints against Google's account management practices, to saboteurs of 5G antennas who reject the total digitization of the world, to Torontoresidentswho are thwarting Google's grandsmart cityproject, to doctors whoarefree softwareactivistsseeking to protect health data.

This emphasis on different ethical imperatives, which are both opposing and complementary, is consistent with Edgar Morin'scomplex thinkingon ethics, which accepts resistance and disruption as inherent to change.

Bernard Fallery, Professor Emeritus in Information Systems, University of Montpellier

This article is republished fromThe Conversationunder a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.