Assessing the structural integrity of Notre Dame's vaults after the fire

A cultural disaster, the Notre Dame fire in 2019 also provides an opportunity to increase our knowledge: the debris from the famous cathedral is a valuable witness to the past! This series follows the scientific work being carried out at Notre Dame, where charred wood and metal parts reveal their secrets. After the first episodes on the roof structure and the origin of the wood, we turn our attention to the structure of the cathedral and, in thisfourth installment, its masonry.

Stéphane Morel, University of Bordeaux; Frédéric Dubois, University of Montpellier; Jean-Christophe Mindeguia, University of Bordeaux; Paul Nougayrede, National School of Architecture (ENSA) Paris-Malaquais – PSL; Pierre Morenon, INSA Toulouse and Thomas Parent, University of Bordeaux

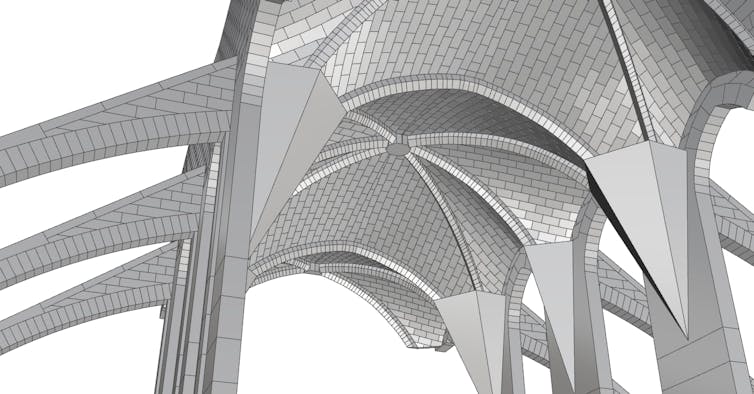

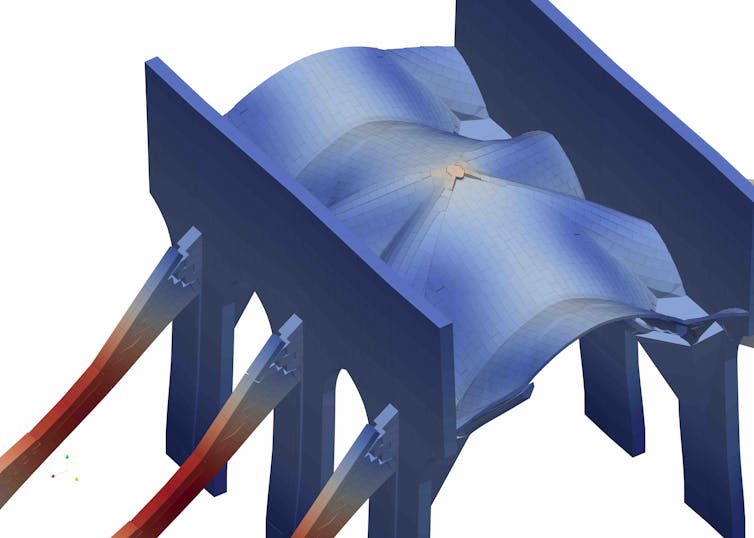

Maurizio Brocato and Paul Nougayrede, GSA Paris-Malaquais, Provided by the author

In April 2019, in the aftermath of the fire that struck Notre-Dame Cathedral, the CNRS and the Ministry of Culture set up the "Notre-Dame scientific project" to bring together and organize initiatives from the French scientific community.

Our "Structures" working group is focused on the mechanical assessment of the cathedral's load-bearing structures, particularly the masonry and roof frames. We were quickly called upon by the restoration project managers to assess the current stability of the cathedral's high vaults, which were affected by the fire.

Although parts of the vaults collapsed during the disaster, mainly due to impacts with elements of the spire or roof structure, the vast majority of the vaults remained intact. This is not surprising, as the vaults were originally designed as a fire protection system by preventing burning elements from falling! They fulfilled their role well, but their stability is crucial to the safety of the site.

In addition, the vaults are now considered a true architectural masterpiece of the Gothic style—and are, of course, subject to maximum conservation.

Unfortunately, no modern calculation method is currently available in technical design offices to accurately model the mechanical behavior of such structures in order to assess the safety of the site and the effectiveness of the support measures put in place by the project manager.

That is why scientific expertise is necessary here... and faced with highly complex mechanisms, our working group had to develop new approaches.

A masonry gem, a challenge for modelers

Inthe 20th century, the construction of large buildings gradually moved away from masonry in favor of metal and reinforced concrete; the focus of calculation/modeling then shifted to these modern materials.

[Nearly 70,000 readers trust The Conversation newsletter to help them better understand the world's major issues. Subscribe today]

Furthermore, the mechanical behavior of a masonry structure is extremely complex to understand: masonry made of cut stone, such as that used in Notre-Dame Cathedral, is similar to a composite material, anisotropic (a material whose mechanical properties vary depending on the direction considered within the material) and heterogeneous, consisting of blocks of cut stone assembled with thin joints of lime mortar, where the stone-mortar interface is an area of mechanical weakness.

Thus, damage to masonry made of dressed stone will mainly occur at the stone-mortar interfaces and, as a result, cracking of the masonry will occur along clearly identified lines.

Stability and flexibility of construction

Thanks to this construction method, Notre-Dame has high mechanical stability, characterized by great flexibility: relative movement between blocks is allowed by cracking at the stone-mortar interfaces, which induces a significant capacity to dissipate mechanical energy via friction at these crack planes.

It is the cracking at the stone-mortar interfaces that gives masonry its rich mechanical behavior, and at the same time makes it difficult to model mechanically with precision.

Although modeling the mechanical behavior of masonry is currently the subject of numerous developments, none of the methods developed to date can claim to provide an exhaustive description of the behavior of this heterogeneous material.

The studies conducted by our scientific consortium were therefore based on a comparison of different complementary mechanical modeling methods in order to obtain a reliable estimate of the post-fire mechanical behavior of the high vaults of Notre-Dame.

Maurizio Brocato and Paul Nougayrede, GSA Paris-Malaquais, Provided by the author

These methods are based on:

- either using a "continuous" approach: masonry is modeled as a single continuous material with elastic properties and breaks equivalent to those of the composite masonry material;

- either using a block-by-block or "discrete" approach: interactions between blocks describe the mechanical behavior conferred by mortar joints and their interfaces.

The discrete approach will more naturally and rigorously capture the divided nature of masonry behavior, which is conferred by the assembly of blocks and the morphological influence of the layout, compared to the continuous approach, but at the cost of longer mesh generation and model calculation times. On the other hand, the discrete approach will fail to describe the breakage of blocks, whereas the continuous approach will describe it accurately.

These two examples illustrate the complementary nature of discrete and continuous approaches; comparing these approaches ultimately allows for a more accurate understanding of the simulated mechanical responses of the modeled structures.

What differences are there before and after the fire?

A pre-fire assessment was first carried out to quantify the change in the stability of the vaults after the fire.

This initial work shed light on the stages involved in constructing the vaults and flying buttresses. Pre-fire modeling also revealed that the morphological differences observed between the thin vaults of the choir (12 to 15 centimeters thick) and the thicker vaults of the nave (19 to 25 centimeters thick) result in less thrust on the vaults than on the flying buttresses in the choir, and vice versa in the nave.

Modeling of the fire led to the identification of the physical phenomenon responsible for most of the post-fire damage observed on the cathedral: thermal expansion.

In fact, the "swelling" of materials due to the increase in their temperature during the fire seems to be a more significant factor than the decrease in the mechanical properties of the materials themselves (this decrease is linked to the rise in temperature and the saturation of the materials with water used to extinguish the fire).

Simulate reinforcement techniques

On this basis, the solution chosen by the project manager to reinforce the burnt vaults was simulated in order to assess the risk-benefit ratio of this solution and the possible adaptations that could increase its effectiveness (for example, with regard to the modulus of elasticity and thickness of the screed or the behavior of the vault-screed complex under mechanical stress).

The work of the "Structures" working group is set to continue until 2024, when restoration work on the cathedral is expected to be completed. At the same time, the group's members are developing a hybrid masonry modeling tool, consisting of the simultaneous use of discrete and continuous approaches.

Frédéric Dubois (LMGC-Montpellier), Paul Taforel (MiMeTICS engineering, LMGC spin-off), Pierre Morenon (TTT platform at LMDC-Toulouse), Maurizio Brocato and Paul Nougayrede (GSA-Paris), Jean-Christophe Mindeguia, Thomas Parent, and Stéphane Morel (I2M-Bordeaux, study coordination) are co-authors of this article..![]()

Stéphane Morel, University Professor, University of Bordeaux; Frédéric Dubois, Research Engineer at the CNRS, University of Montpellier; Jean-Christophe Mindeguia, Senior Lecturer in Civil Engineering, University of Bordeaux; Paul Nougayrede, PhD student in architecture, École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture (ENSA) Paris-Malaquais – PSL; Pierre Morenon, Engineer and Researcher in Civil Engineering within the LMDC's technology transfer division. Specialist in numerical calculation methods for structures. INSA Toulouse and Thomas Parent, Senior Lecturer in Civil Engineering, University of Bordeaux

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.