What if the Y chromosome hadn't evolved as expected?

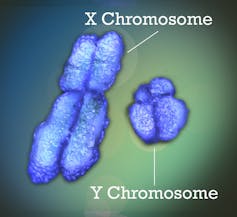

It is one of the most well-known facts in genetics: women are XX and men are XY. In humans, chromosomes determine sex, and this particular pair, the23rd, is the most surprising. It is the only pair of chromosomes where two versions with enormous differences coexist. So much so that it is even difficult to recognize in this pair two chromosomes that were ancestrally very similar but which, over millions of years of evolution, have become unrecognizable.

Thomas Lenormand, University of Montpellier and Denis Roze, Sorbonne University

Why did sex chromosomes evolve to become so unique? This question has been puzzling geneticists for nearly a century. Several hypotheses have been proposed over time, and one theory has gradually gained ground. However, this long-standing theoretical construct has just been turned upside down by a new model that challenges the established view.

The X-Y dichotomy

NIH/Flickr, CC BY-NC

The X chromosome is fairly commonplace, with nearly 800 genes encoding proteins. The Y chromosome, on the other hand, is much stranger: smaller (about one-third the length of the X chromosome), it has only about 60 genes. However, these two chromosomes do form a "pair." During sperm production, they pair up and recombine over a small section (recombination is an exchange of genetic material, in this case between the two chromosomes of the same pair), demonstrating their ancestral homology. However, 95% of the Y chromosome no longer recombines at all. The X chromosome recombines over its entire length in XX females during egg production.

Finally, another oddity is that only one X is expressed in females. This means that genes are read to produce proteins from a single X chromosome, either the one inherited from the father or the one inherited from the mother, randomly depending on the cell. This allows for "dosage compensation," so that genes carried on the X chromosome are expressed at the same level in males and females.

Widespread differences in living organisms

One might think that these eccentricities are unique to humans. This is not the case: they are in fact extremely common among animals, and even plants, although the details vary.

However, recombination is regularly observed to cease on sex chromosomes, a non-recombining chromosome (Y) that contains few functional genes (it is "degenerate"), as well as dosage compensation.

These regularities quickly caught the attention of geneticists, who began searching for a theory to explain why recombination stops on these chromosomes, and why this cessation of recombination is associated with degeneration. These same geneticists also quickly realized that answering this question might also shed light on a more general question that was even more pressing for them: the role of recombination in evolution.

The role of recombination

Recombination during gamete production allows for genetic "shuffling." This is an essential feature of sexual reproduction and undoubtedly the key factor explaining the advantage of sex over asexual clonal reproduction. The degeneration of non-recombining sex chromosomes seems to be real-world proof of the importance of recombination in maintaining genome integrity in the face of a constant flow of deleterious mutations that alter genetic information.

In fact, most chromosomes carry mutations, which can be passed on from one generation to the next when their effect on the survival or fertility of organisms is not too significant. The mutation-free version of a chromosome fragment may be quite rare within a population, and may even disappear if the individuals carrying it do not leave any descendants. When this happens, a mutation-free fragment can only be recreated through recombination between chromosomes carrying mutations at different locations. As a result of this process, non-recombining areas of chromosomes are expected to gradually accumulate mutations.

The absence of recombination could therefore explain the degeneration of the Y chromosome. But that does not entirely resolve the question: why on earth do sex chromosomes stop recombining if this cessation leads to degeneration?

The theory of "sex-antagonistic" genes

Until our work, this was explained by the theory of "sex-antagonistic" genes. Males and females differ in many characteristics: this is sexual dimorphism. For many genes, there are therefore versions (alleles) that are advantageous for one sex and disadvantageous for the other.

benjamint444/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

If these "sex-antagonistic" genes are common, we can expect to find them on the sex chromosomes. Suppressing recombination (and therefore the exchange of alleles between the X and Y chromosomes) can then become advantageous. If an allele that is advantageous in males is found on a Y chromosome that no longer recombines, it will remain on that Y chromosome: it will always be found in males but never in females.

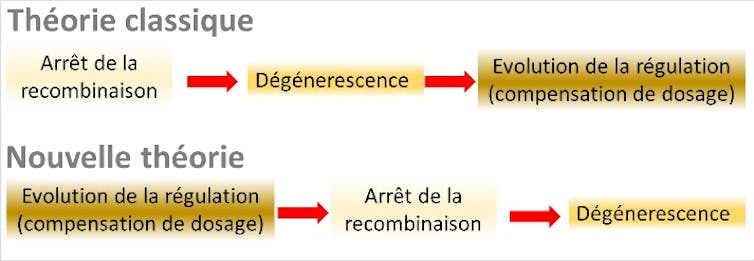

A comprehensive theory of sex chromosome evolution in three stages has thus emerged. Stage 1 is the cessation of recombination on the Y chromosome, caused by the presence of sex-antagonistic genes on the sex chromosomes. Stage 2 is the accumulation of deleterious mutations (degeneration) following the cessation of recombination. Stage 3 is the evolution of dosage compensation to compensate for the lack of expression of X genes in males.

This theory had the advantage of being very elegant, because it was very general. However, several subsequent observations gradually called this structure into question and reopened the theoretical debate.

A new theory

To do this, we started with the only "ingredients" that seem essential to explain the evolution of sex chromosomes: recombination arrest events on the Y chromosome (which are not irreversible), deleterious mutations (degeneration cannot occur without them), and gene expression regulators that can modulate their expression levels (dosage compensation cannot occur without them).

To our surprise, these ingredients, especially the last one, which had never been formally incorporated into classical theory, proved to be sufficient. Our research has uncovered a global process that is entirely different from "classical" theory, where all causal relationships are reversed and "sex-antagonistic" genes become unnecessary.

Thomas Lenormand, Provided by the author

Like the classical theory, this new theory assumes an ancestral situation in which a gene carried by a pair of "normal" chromosomes (autosomes) determines the sex of individuals. Two different forms of this gene (or alleles, denoted M and F) coexist, with MF individuals developing into males and FF individuals into females.

It is then assumed that chromosomal inversions can occur: an inversion corresponds to a "reversal" of part of the chromosome, with the genes located in this part then finding themselves in reverse order. These inversions are a fairly rare form of mutation, but nevertheless occur from time to time within populations. They have the effect of preventing (at the level of the inversion) recombination between inverted and non-inverted chromosomes. This is because the different order of the genes prevents the chromosomes from pairing correctly in this area.

When an inversion involving the M allele (which determines male sex) occurs, it may be advantageous if the genes it contains carry fewer deleterious mutations than average. In this case, its frequency will increase over generations until all males carry this inversion. As a result, chromosomes carrying the F and M alleles become X and Y "proto-chromosomes," no longer recombining over part of their length (in the inversion zone).

However, the cessation of recombination eventually causes an accumulation of deleterious mutations on the chromosome carrying the M allele (the one carrying the F allele continues to recombine in females). This accumulation of mutations can promote either a return to recombination (for example, through a new chromosomal inversion restoring the initial order of the genes), or a reduction in the expression of the mutated genes carried by the proto-Y, which will be compensated for by an increase in the expression of the proto-X genes: this is the beginning of dosage compensation. When this occurs quickly enough, it prevents any return to the previous state: restoring recombination would destroy this delicate balance between the expression levels of the X and Y genes.

The computer simulations we have carried out thus show a gradual cessation of recombination, in successive "layers" corresponding to different inversions stabilized by the evolution of dosage compensation, without the need to invoke the existence of sex-antagonistic genes.

By completely renewing our vision of possible scenarios for the evolution of sex chromosomes, this new theory opens up a vast field of experimentation and empirical testing. It also shows the importance of taking into account the mechanisms regulating gene expression in evolutionary theory. Finally, it could suggest that taking into account the evolution of regulators could be one of the keys to solving the mystery of the maintenance of sexual reproduction in plants and animals.![]()

Thomas Lenormand, Research Director, University of Montpellier and Denis Roze, Researcher in evolutionary genetics, Sorbonne University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.