Exploring the deep sea with environmental DNA, or how to reveal unexpected biodiversity

The ocean covers two-thirds of the planet, more than half of which is over 3,000 meters deep. We know very little about the biodiversity that inhabits the abyss.

Sophie Arnaud Haond, University of Montpellier

Given the low density of life in these environments, describing species or conducting diversity inventories requires handling considerable quantities of sediment, which must be brought up through thousands of meters of water column and sorted for weeks in the laboratory. Thus, describing a single species or conducting a diversity inventory of a few cubic centimeters of sediment can take weeks.

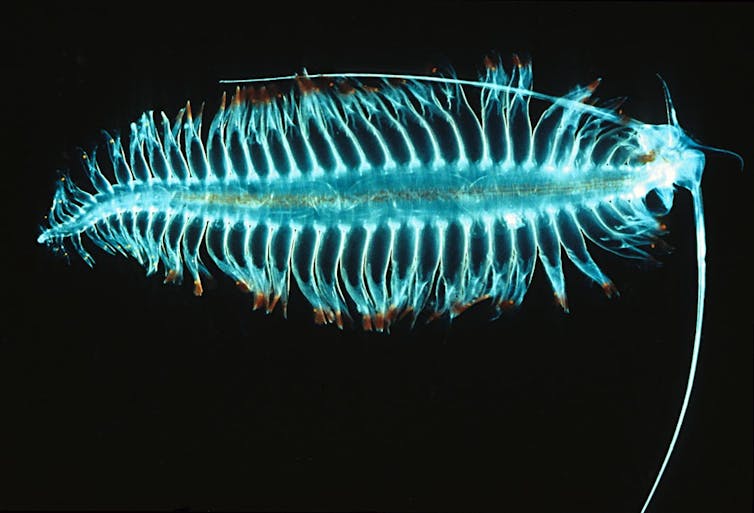

Uwe Kils/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

However, although the deep sea is far from sight, it is not immune to human impacts such as pollution (agricultural inputs, maritime traffic, etc.) or the direct impact of the exploitation of its many resources (oil drilling, fishing, etc.). Among the exploitation projects in the deep sea, the exploitation of energy and mineral resources, such as the nodule zones in the Pacific, is becoming increasingly advanced.

Gaining a better understanding of the extent of marine biodiversity is becoming a considerable challenge, both in terms of knowledge of living organisms and their evolution, and in terms of conservation and the implementation of monitoring and measures to conserve and minimize environmental impacts. It is in this context that Ifremer launched the "Pourquoi Pas les Abysses" project, which was followed by the France Génomique "eDNAbyss" project: both are based on the use of what is knownas "environmental DNA," or eDNA.

What is environmental DNA?

Although DNA is the carrier of heredity and the signature of living beings (as opposed to water, rocks, etc.), it can be extracted from the environment.

Living beings leave traces of their passage in their environment: microdroplets of saliva, hair, mucus, skin, scales, excrement, decomposing cells, etc. These DNA-laden remains float in the air, carried by currents, and settle in the soil or sediment. Just like forensic investigators examining suspicious DNA at crime scenes, biologists extract DNA from environmental samples to identify the species that live there or have passed through.

Uwe Kils/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

We now know how to identify specific fragments in genome extracts or genome mixtures (such as in DNAe) that vary sufficiently between species for their sequence to enable us to recognize the major groups to which they belong (species, genera, families, etc.). By analogy with commercial barcodes, these fragments are called " barcodes."

The discovery of unexplored areas of biodiversity, in space and time

In microbiology, this type of advance has had a major impact, since the vast majority of microbial organisms, bacteria, and archaea cannot be cultured: their characterization has only been possible thanks to eDNA. The tree of life has been enriched with a large number of major lineages, notablyarchaea that inhabit hot springs and the ocean floor, which are the subject of fundamental hypotheses for understanding the ancestral diversification of life into three kingdoms (bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes).

In ecology in the broad sense, the ability of DNAe approaches to detect and differentiate cryptic species (impossible to recognize on the basis of morphological criteria) has been exploited in a variety of environments. For example, the Tara Ocean expedition, combining morphological and DNA analyses, revolutionized our understanding of plankton diversity in the oceans by revealing the existence of nearly fifteen times more plankton lineages than the 11,000 previously described.

Beyond the invisible or inaccessible in space, the exploitation of DNA contained in sediments also makes it possible to reconstruct past communities and infer the impact of local or global changes. Analyses carried out in Brest harbor have shown the disruption of microalgae communities after World War II and the introduction of agricultural inputs, while analysis of contemporary insect communities in pine forests reflects the decline of the habitat in the face of climate variations.

Implementation that is both simple and careful

To begin with, the air or water must be filtered, or soil or sediment collected, but this relatively simple process requires extreme precautions, as the DNA contained in these samples is often present in very small quantities. Life is rare at the bottom of the sea, even though it is very diverse, and the DNA contained in a handful of sediment is present in small quantities compared to that carried by researchers or naturally accumulated on the workstations of ships. It is often even rarer in seawater, where it degrades very quickly after the death of cells. It is therefore essential to protect it from possible contamination from sources with much higher DNA content, such as the hands or saliva of those handling it, for example.

After carefully packaging them to protect them from contamination and transporting them to the laboratory, the samples undergo environmental DNA extraction using various methods (chemical, mechanical, filtration), depending on the objective and the environmental substrate, whether it be fresh water, sea water, sediment, soil, etc. Once the DNA has been extracted, it is used to create different types of "libraries" depending on the scientific objective and the living organisms targeted.

The deep environment, that unknown quantity

The marine environment, in its three dimensions, is vast: it represents more than 95% of the Earth's biome. Obtaining a comprehensive view of its diversity requires standard study methods across its various compartments and ecosystems. One of the advantages of DNA-based approaches is that they allow the scientific community to pool the results obtained on a variety of ecosystems, like a giant puzzle that takes shape as pieces are added.

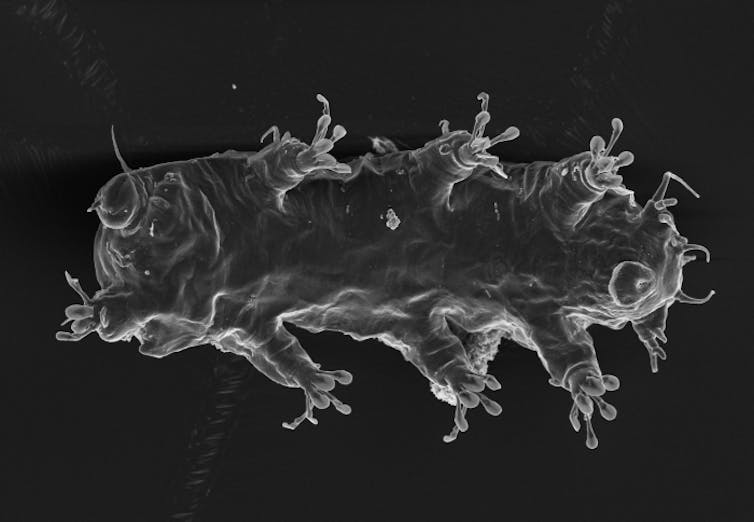

Daniel Leduc, World Register of Marine Species, CC BY-NC-SA

To do this, as part of the "Pourquoi Pas les Abysses" project, as was done in Tara Ocean, we developed a dual approach to characterize both prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea), unicellular organisms, and eukaryotes (unicellular protists, animals, fungi, etc.). All organisms can be studied by constructing "metabarcode libraries" targeting small fragments of genomes that allow species or lineages to be recognized, and to refine the identification of prokaryotes, their complete genomes are reconstructed using " metagenome libraries."

The metabarcoding required a three-stage pilot study. The first step was to select different sampling methods for benthic fauna (living in sedimentary bottoms) and pelagic fauna (living in the water column). DNA can be stored for long periods in sediment, so the next step was to select an extraction method that would facilitate contemporary biodiversity inventories. Finally, a set of molecular probes selects the barcodes that reveal diversity across the tree of life, from bacteria to animals.

These protocols, implemented by the "eDNAbyss" project, have generated billions of sequences from samples collected from the Mediterranean Sea to the Pacific Ocean, at depths ranging from 300 to 10,000 meters.

C. Schulze and A. Schmidt-Rhaesa, World Register of Marine Species, CC BY-NC-SA

Based on the initial results, it was possible to combine benthic biodiversity data (associated with sediment), including data produced by the "Pourquoi pas les Abysses?" and "eDNAbyss" projects, with the ADNe inventories of biodiversity in the water column carried out by Tara Ocean. The results highlighted several major elements in our understanding of the distribution of marine biodiversity. They revealed a level of diversity three times higher in benthic sediment communities than in pelagic communities in the water column. Among this great diversity on the seabed, more than a third is still completely unknown: the barcodes do not correspond to any species described in the reference databases.

Comparing the plankton species present at the surface and found in the sediment also made it possibleto identify major contributors to the biological carbon pump, a key process for the climate.

This first step represents an encouraging demonstration of the capacity of environmental DNA-based approaches to enable not only standardized and interoperable inventories of diversity in the three dimensions of the ocean, but also a better understanding of the major processes to which they contribute. And the majority of the results are still being analyzed...![]()

Sophie Arnaud Haond, Researcher, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.