Science images: new materials for trapping or filtering molecules

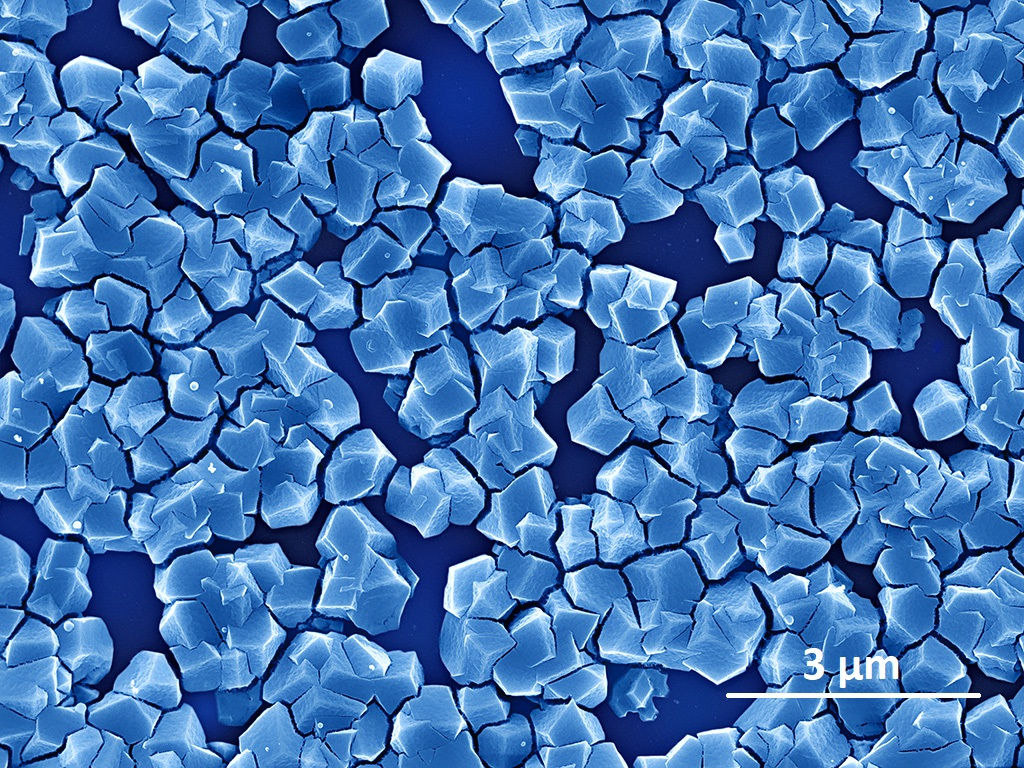

This image was taken during the formation of an ultraporous membrane, which can be used to "sift" molecules or trap them. These materials are being developed for applications such as separating gas mixtures, purifying air or water, and administering active pharmaceutical ingredients more effectively.

Martin Drobek, University of Montpellier; Anne JULBE, University of Montpellier and Didier Cot, University of Montpellier

These materials are composed of elementary bricks that form meshes of impressive diversity. The bricks can be assembled in any way, like a real "Lego game" on a nanometric scale.

They are made up of metal ions linked together by organic molecules that act as cement and spacers. These networks, known as " metal-organic frameworks " (MOFs), enable the formation of an almost unlimited number of molecular structures with adjustable physical and chemical properties. Some MOFs can accommodate and transport small gas molecules, such as hydrogen, while others can trap and release large molecules, such as active pharmaceutical ingredients.

Their hybrid nature, both organic and inorganic, gives MOFs a very flexible structure. Their extremely high porosity, with a network of small, regular, well-ordered pores, explains their low density and large accessible internal surface area, equivalent to the size of a soccer field for a single gram of material! Such a surface area—several thousand square meters—far exceeds that of benchmark porous materials such as zeolites or activated carbons.

Most MOFs are, by default, prepared and used in powder form, but to fully exploit their potential for large-scale and industrial applications, they generally need to be "shaped," for example into granules or thin layers, and production costs must be competitive.

Sifting molecules through a highly selective porous network

At the European Membrane Institute in Montpellier, we are interested in these materials for the development of membranes that can separate gas mixtures through a "molecular sieving" effect. Deposited on the surface of gas sensors, such membranes can improve the selectivity of toxic or explosive gas detection, thanks to their preferential transport in the pores.

By adjusting the length of the organic molecules that connect the metal centers, the pore size can be adjusted. Most MOFs are microporous (with pores less than 2 nanometers in diameter) and their pores can accommodate and transport not only hydrogen but also other small gas or vapor molecules such as water, oxygen, or carbon dioxide.

Currently, we are paying particular attention to hydrogen detectors in relation to the safety issues posed by the production, transport, storage, and use of this gas. The strategy consists of covering the sensor's sensitive material with a layer of a specific type of "MOF." The separating effect of this molecular sieve allows hydrogen to diffuse easily to the sensor while rejecting other gases in the mixture.

Trapping molecules as if in cages

However, given the diversity of possible structures and functionalities, the scope of application of MOFs is much broader. Their pores correspond to the dimensions of a wide variety of common molecules and they can be used as nano-cage sponges for the selective adsorption of these molecules.

For these applications, mesoporous MOFs (diameter greater than 2 nanometers) are also of interest. Their main advantage lies in their ability to encapsulate large molecular systems, such as proteins or drugs, nanoparticles, or macromolecular assemblies (groups of giant molecules).

We can therefore envisage the development of complex MOF-type architectures. to store and generate energy, decontaminate air or water through the selective adsorption of harmful compounds; or in the field of healthcare, for example for the controlled distribution of active ingredients.![]()

Martin Drobek, CNRS Research Fellow, University of Montpellier; Anne JULBE, Director of Research CNRS, specialist in ceramic and hybrid membranes, University of Montpellier and Didier Cot, Engineer, Head of the Electron Microscopy and Photonics Division, European Institute of Membranes, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.