Most industrial fishing in marine protected areas is not monitored.

Are marine protected areas really effective in protecting marine life and small-scale fishing? While, following UNOC-3, countries such as France and Greece are announcing the creation of new areas, a study published on July 24 in the journal Science shows that the majority of these areas remain exposed to industrial fishing, much of which escapes public oversight. A large proportion of marine areas do not comply with scientific recommendations and offer little or no protection for marine life.

Raphael Seguin, University of Montpellier and David Mouillot, University of Montpellier

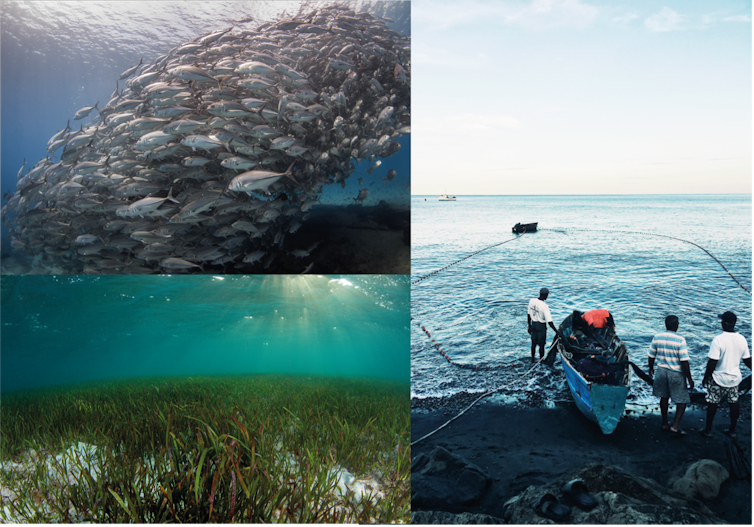

The health of the ocean is at risk, and by extension, so is ours. The ocean regulates climate and rainfall patterns, feeds more than three billion people, and supports our cultural traditions and economies.

Historically, industrial fishing has been the primary source of destruction of marine life: more than a third of fish populations are overexploited, a figure that is probably underestimated, and populations of large fish have declined by 90 to 99 percent depending on the region.

Added to this today is global warming, which is having a major impact on most marine ecosystems, as well as new and as yet poorly understood pressures linked to the development of offshore renewable energy, aquaculture, and mining.

Marine protected areas: an effective tool for protecting the ocean and humanity

Faced with these threats, we have a proven tool for protecting and restoring marine life: marine protected areas (MPAs). The principle is simple: we are overexploiting the ocean, so we need to designate certain areas where we regulate or even prohibit activities that have an impact, to allow marine life to regenerate.

MPAs aim to achieve triple ecological, social, and climate effectiveness. They enable the recovery of marine ecosystems and fish populations that can reproduce there. Some allow only small-scale fishing, creating non-competitive zones that protect more environmentally friendly methods and create jobs. They also allow recreational activities such as scuba diving. Finally, they protect environments that storeCO2 and thus contribute to climate regulation.

As part ofthe Kunming-Montreal Global BiodiversityFramework signed at COP 15, countries have committed to protecting 30% of the ocean by 2030. Officially, more than 9% of the ocean's surface is now under protection.

To be effective, all MPAs should, according to scientific recommendations, either prohibit industrial fishing and exclude all human activities, or allow certain activities, such as artisanal fishing or scuba diving, depending on the level of protection. In practice, however, most MPAs do not follow these recommendations and do not exclude industrial activities that are most destructive to marine ecosystems, rendering them ineffective or even harmful.

Real protection or communication tool?

In fact, in order to quickly achieve international protection targets and proclaim their political victory, governments often create large protected areas on paper, but without any real effective protection on the ground. For example, France claims to protect more than 33% of its waters, but only 4% of these are subject to regulations and a truly effective level of protection, of which only 0.1% are in metropolitan waters.

At the UN Ocean Summit held in Nice in June 2025, France, which opposes European regulations aimed at banning bottom trawling in MPAs, announced that it would designate 4% of its metropolitan waters as highly protected areas and ban trawling there. The problem is that almost all of these areas are located in deep waters... where bottom trawling is already prohibited.

The situation is therefore critical: in the European Union, 80% of marine protected areas in Europe do not prohibit industrial activities. Worse still, the intensity of bottom trawling is even higher in these areas than outside them. Worldwide, most MPAs allow fishing, and only a third of large MPAs are truly protected.

Furthermore, the true extent of industrial fishing in MPAs remains largely unknown worldwide. Our study therefore sought to partially fill this gap.

The reality of industrial fishing in protected areas

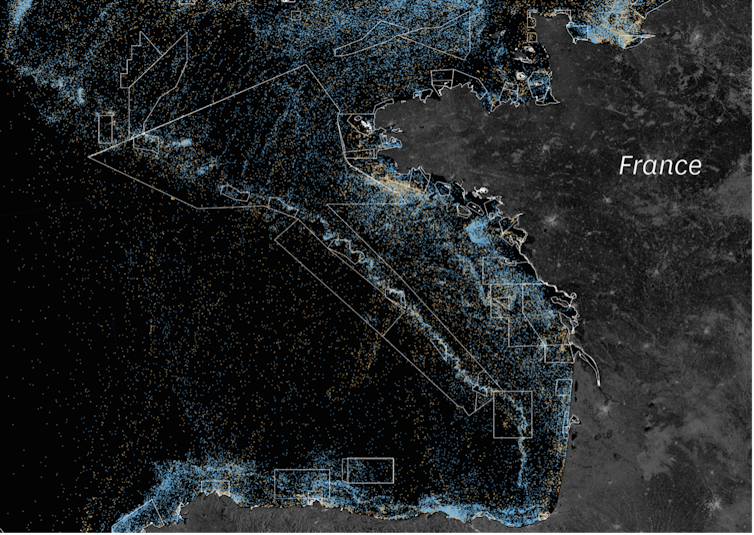

Historically, it has always been very difficult to know where and when boats are going to fish. This made it very difficult for scientists to monitor industrial fishing and its impacts. A few years ago, the NGO Global Fishing Watch published a dataset based on the Automatic Identification System (AIS), a system initially designed for safety reasons, which makes the position of large fishing vessels around the world publicly and transparently available. In the European Union, this system is mandatory for all vessels over 15 meters in length.

The problem is that most fishing vessels do not broadcast their position via the AIS system all the time. There are various reasons for this: they are not necessarily required to do so, the vessel may be in an area where satellite reception is poor, and some deliberately switch it off to conceal their activities.

To fill this knowledge gap, Global Fishing Watch has combined AIS data with satellite images from the Sentinel-1 program, which can detect ships. This makes it possible to distinguish between ships that are tracked by AIS and those that are not, but are detected on satellite images.

The areas are effective, but that's because they are located where few boats go fishing in the first place.

Our study looks at the presence of fishing vessels tracked or not tracked by AIS in more than 3,000 coastal MPAs around the world between 2022 and 2024. During this period, two-thirds of industrial fishing vessels present in MPAs were not publicly tracked by AIS, a proportion equivalent to that observed in unprotected areas. This proportion varied from country to country, but untracked fishing vessels were also present in the marine protected areas of EU member states, where the transmission of position via AIS is mandatory.

Between 2022 and 2024, we detected industrial fishing vessels in half of the MPAs studied. Our findings, consistent with another study published in the same issue of Science, show that the presence of industrial fishing vessels was indeed lower in truly protected MPAs, the few that prohibit all extractive activities. This is good news: when regulations exist and are effectively managed, MPAs effectively exclude industrial fishing.

However, we attempted to understand the factors influencing the presence or absence of industrial fishing vessels in MPAs: is it the actual level of protection or the location of the MPA, its depth, or its distance from the coast? Our results indicate that the absence of industrial fishing in an MPA is more related to its strategic location —very coastal, remote, or unproductive areas that are therefore not very exploitable—than to its level of protection. This reveals an opportunistic strategy for locating MPAs, which are often placed in areas where there is little fishing in order to more easily achieve international objectives.

An underrated and underappreciated fruit

Finally, one question remained: does the detection of a fishing vessel on a satellite image mean that the vessel is actually fishing, or is it simply passing through? To answer this question, we compared the number of vessel detections by satellite images in an MPA with its known fishing activity, estimated by Global Fishing Watch using AIS data. If the two indicators are correlated, and the number of vessel detections on satellite images is linked to a greater number of fishing hours, this implies that it is possible to estimate the share of "invisible" fishing activity from detections not tracked by AIS.

We found that the two indicators were highly correlated, showing that satellite detections are a reliable indicator of fishing activity in an MPA. This reveals that industrial fishing in MPAs is much more significant than previously estimated, by at least one-third according to our results. However, most research and conservation organizations, NGOs, and journalists rely on this single source of public and transparent data, which reflects only a limited part of the reality.

Many questions remain: the resolution of satellite images prevents us from seeing vessels less than 15 meters long and misses a significant proportion of vessels between 15 and 30 meters. Our results therefore underestimate industrial fishing in protected areas and completely overlook small vessels less than 15 meters long, which can also be considered industrial fishing, particularly if they adopt industrial methods such as bottom trawling. In addition, the satellite images used cover most coastal waters but not most of the high seas. Island or offshore MPAs are therefore not included in this study.

Towards genuine protection of the ocean

Our findings are consistent with those of other studies on the subject and lead us to make three recommendations.

On the one hand, the quantity of marine protected areas does not determine their quality. The definitions of MPAs must follow scientific recommendations and prohibit industrial fishing, otherwise they should not be considered true MPAs. Secondly, MPAs must also be located in areas subject to fishing pressure, not just in areas that are under-exploited. Finally, fisheries monitoring must be strengthened and made more transparent, in particular by generalizing the use of AIS on a global scale.

In the future, thanks to high-resolution optical satellite imagery, we will also be able to detect the smallest fishing vessels, giving us a broader and more comprehensive view of fishing activities around the world.

For now, the urgent priority is to align the definitions of marine protected areas with scientific recommendations and to systematically ban industrial activities within these areas in order to build genuine protection for the ocean.

Raphael Seguin, PhD student in marine ecology, writing his thesis with the University of Montpellier and BLOOM, University of Montpellier and David Mouillot, Professor of Ecology, MARBEC Laboratory, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.