Music in the sights of industrial groups

The French music industry has been shaken up by the unprecedented entry of industrial groups into all areas of its business. The phenomenon began in 2004 with the emergence of Live Nation and the creation of its first festival: Main Square, in Arras.

Emmanuel Négrier, University of Montpellier

Since then, the music world, which had previously been based on a mixed economy and multiple small businesses (subsidized festivals, producers working with a small number of artists, municipal or mixed-economy venues), has been the scene of a wave of acquisitions by a handful of operators.

We are seeing phenomena of diversification and concentration. Diversification is characterized by the entry of companies that were previously specialized in one segment (production, venue management, festivals, record labels, etc.) into other segments. These companies may be primarily French, such as Fimalac, Vente-privée, Morgane, and LNEI, or multinational, such as Vivendi, AEG, and Live Nation. Concentration is reflected in the takeover, by a limited number of companies, of companies that were previously interdependent but belonged to sub-sectors subject to specific expertise and rules. Mergers therefore pose a challenge in terms of coordinating business lines, but also in terms of statuses that were previously separate.

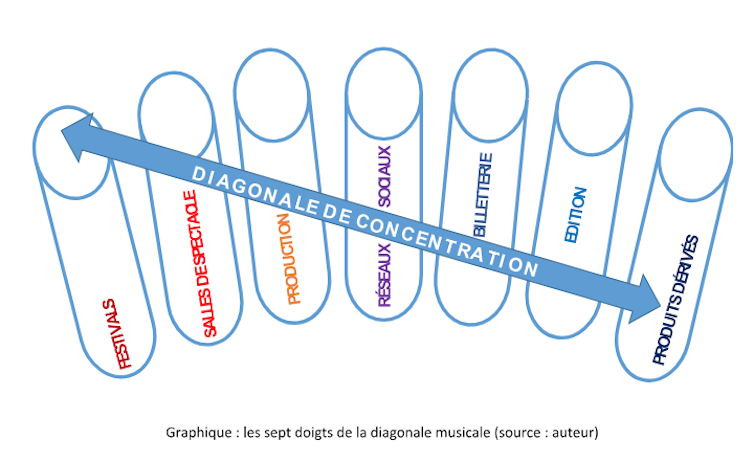

This concentration is " diagonal " because it draws on the three types of concentration traditionally distinguished in industrial economics, particularly in the media sector (financial, horizontal, and vertical). Its motives are varied, and not all of them are driven by profitability. This is perhaps what makes it enigmatic and fragile.

A " diagonal " concentration

The first type of concentration is financial and allows one company to take control of another while allowing it to retain formal autonomy and brand identity. Fimalac, led by Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière, fits this model well, with revenues of nearly €250 million (in 2016) corresponding to an entertainment division (3S Entertainment) which, at the end of 2016, comprised 101 theaters and 12 production companies, some of which, such as Miala, organize festivals. The aim of preserving brand identity is to avoid abruptly breaking with the personalization that contributes to the value of these companies, which are often small-scale and fragile. This does not prevent economies of scale, such as the pooling of ticketing activities, for example.

In this first type of concentration, we find players who specialize in several niches at once without embracing the entire artistic value chain. Fimalac's strategy claims to exclude the " 360-degree " approach in the name of artistic diversity, while Vivendi (nearly €11 billion in 2016) intends to move from development to production and touring of artists, to their promotion in the media and the recording industry, using all of the group's resources.

The second form of concentration is horizontal and involves the absorption of competitors or the duplication of an event, for example, within the same sub-sector. One example is Live Nation and its variations of the same festival in several countries, such as Lollapalooza, with some 3,300 artists under contract touring the world, notably during the 25,500 concerts organized annually by a group whose turnover in 2016 was €7.5 billion. This phenomenon is not as recent as it seems, since in the classical music sector, René Martin had, on a more modest scale (and without involving the same level of capital as the ownership of a production company or festival), while also taking over the management of other festivals in France (Saint-Chartier, La Roque-d'Anthéron).

We can also mention the Lagardère group and its strategy of producing artists, in the same way that the firm had initiated the management of the careers of top athletes. This focus on the same niche activity generates expectations of economies of scale on a larger scale than in the previous case. For example, duplicating an event allows a number of costs to be shared: graphic design, artist fees, technical equipment, communication, etc.

The third form of concentration is vertical and involves the absorption of customers or suppliers. This is closer to " 360 degrees," more or less completely, capitalizing on the interdependencies that exist between the initial risks (in developing an artist, creating a label, a cultural venue, etc.) and the profits derived from all possible uses of an artist or a work. We find the case of Fimalac, Vivendi, and Live Nation, already mentioned. We can also mention the case of Sony, on the equipment and record side, whose investment in artist production is of course linked to the collapse of the profitability of recorded music and the shift of profit sources to live performance.

Diagonal concentration is closely linked to the fact that it is impossible to associate operators with a single niche. It is by crossing each of these fields (venue management, festival organization, production, publishing, digital services, ticketing, merchandise, etc.) that we see the interpenetrations taking place. But how can we explain this sudden industrial passion for music? There is a paradox here that needs to be clarified: most of the strategies implemented by these groups in France (purchasing festivals, venues, labels) are currently resulting in losses. This is strange for captains of industry who cultivate a secrecy that contrasts with the very public nature of their investments. Let's try to shed some light on their motives.

What drives these concentration phenomena?

Five reasons explain these major maneuvers: passion, mediation, vision, attention, and support.

Passion evokes these leaders' emotional connection to music. On the enchanting side, it is the classic pleasure of the prince in mirroring himself in the artist he patronizes. On the strategic side, culture serves to symbolically enhance one's status when one's business success is due to shady stock market activities or dubious sex trade, as Laurent Mauduit pointed out in relation to the media in his 2016 book Main Basse sur l'Information(Main Low on Information).

Mediation is the act of using a privileged position in the music industry to further other, more profitable ventures. Financial losses in music are offset by the fact that in VIP boxes, in exchanges with elected officials on the sidelines of festivals, contracts are signed, support is obtained, and deals are negotiated in the excitement of the moment. Losing (small) means winning (big). All while adorned with the status of hero, savior of French culture, benefactor of the arts. On April 22, 2017, he told Le Monde that his strategy makes his group " the secular arm of the Ministry of Culture " (Le Monde, April 22, 2017, interview by Fabienne Darge and Philippe Dagen).

These leaders' vision is based on the anticipation of deregulation in the sector, which is in line with current trends: the reduction of public subsidies, which they believe distort competition; and the implementation of trade agreements, such as CETA, which exclude the music sector from the scope of cultural exceptions. Today, we are losing in order to win tomorrow. And besides, we are losing very little, since we are buying festivals and venues at prices that take no account of the subsidies paid over the years. For example, the AEG group's acquisition of the Rock en Seine festival took place without any consideration of the significant subsidies granted over the years by the Île-de-France regional council to the event. However, it is reasonable to consider that these subsidies have played a major role in establishing the value of the event, without generating any financial return for the community when it was bought out.

This attention corresponds to the new economy linked to the possibility of using information related to users' practices on social networks or during their exchanges on the Internet. By entering this sector, industrial groups gain access to metadata collected during ticket purchases and exchanges on forums and networks. It is no coincidence that these groups are investing in ticketing services: Ticket Master (Live Nation), Vivendi Ticketing, My Ticket, and Tick&Live (Fimalac). This is where the sources of profit (and standardization of offerings) linked to the attention economy described by Yves Citton lie. The personality inferred from ticket purchases can lead to far-reaching commercial exploitation, starting from an initial act (purchasing a ticket to a show) with extremely positive emotional connotations. The perfect algorithm!

A guarantee in case of hardship

As for the guarantee aspect, it reduces the burden to a purely material level. But it is true that even if we lose a little money, we have nevertheless acquired assets—in the form of theaters, publishers, broadcasters, etc.—which have a value, particularly in terms of real estate, and strengthen the equity of these companies in a relatively uncertain environment. In the event of a bubble bursting, this therefore provides a guarantee in the event of a hard blow.

![]() Once these motives have been explained, doubts remain about their cultural value in France or elsewhere. Naturally, these groups believe that they contribute in their own way to artistic creativity, given the breadth of their artist catalogs. But their growing influence on programming and their control over the most attractive posters confirm the risk that these strategies pose in terms of diversity and increased dependence of artists on these firms. This could be the subject of further reflection, which would also examine ways of counteracting the most harmful effects: standardization of events, price increases linked to higher artists' fees and safety standards, reduction of artistic risk by concentrating lineups around " house ".

Once these motives have been explained, doubts remain about their cultural value in France or elsewhere. Naturally, these groups believe that they contribute in their own way to artistic creativity, given the breadth of their artist catalogs. But their growing influence on programming and their control over the most attractive posters confirm the risk that these strategies pose in terms of diversity and increased dependence of artists on these firms. This could be the subject of further reflection, which would also examine ways of counteracting the most harmful effects: standardization of events, price increases linked to higher artists' fees and safety standards, reduction of artistic risk by concentrating lineups around " house ".

Emmanuel Négrier, CNRS Research Director in Political Science at CEPEL, University of Montpellier, University of Montpellier

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.