The mystery of tardigrades' extreme resilience finally solved?

September 2007. A Russian rocket lifts off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, carrying strange little creatures measuring just one millimeter in length on a ten-day journey around the Earth. These creatures are tardigrades, participating in the European Space Agency's (ESA) Foton-M3 space program.

Simon Galas, University of Montpellier and RICHAUD Myriam, University of Montpellier

What a strange fate for these astronaut tardigrades, which were all aquatic when they first appeared on Earth (probably during the Cambrian period around 500 million years ago).

Tardigrades, also known as water bears, have four pairs of legs and one pair of small eyes. With 1,400 species known today, they can be found everywhere on Earth, from the peaks of the Himalayas to the depths of the oceans.

Tardigrades can lose 95% of their water content.

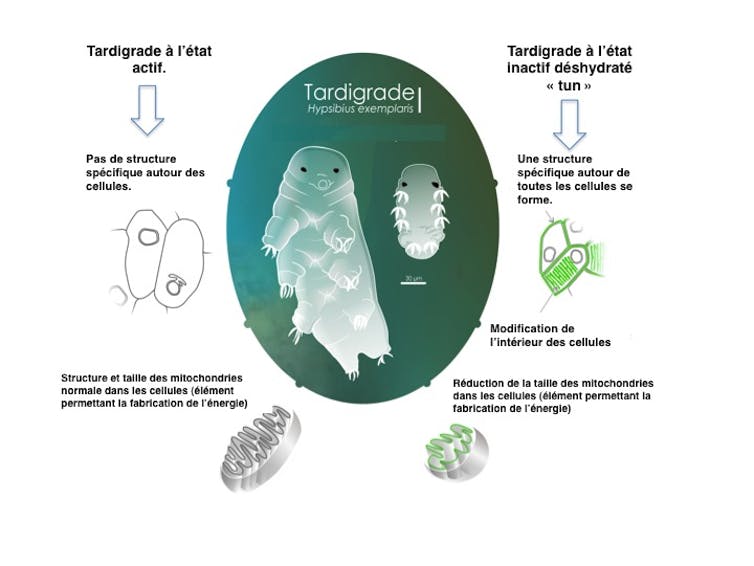

Terrestrial tardigrade species retain a memory of their aquatic origins. As soon as the thin film of water covering its body disappears, the tardigrade undergoes an active transformation that causes it to lose 95% of its water and shrink in size by nearly 40%. In this state, the tardigrade resembles a small barrel, hence the name "tun" used by English speakers to refer to it in this particular state, which is a state ofanhydrobiosis.

Anhydrobiosis is a state of slowed life induced by dehydration. In this particular state, tardigrades are able to withstand extreme conditions.

During this stay in low Earth orbit (altitude 258–281 km above sea level), these tardigrades in a state of suspended animation were exposed to the combined effects of the vacuum of space, cosmic rays, and extreme ultraviolet radiation.

Back on Earth, 12% of these astronaut tardigrades were successfully reawakened by simply placing a drop of water on their bodies. This spectacular revival, which takes less than five minutes in some species, astonished scientists and established tardigrades as the only animals capable of surviving the combined effects of space vacuum, cosmic radiation, and ultraviolet rays in real-life situations.

One might think that this state of slowed-down anhydrobiotic life, or "tun," allows tardigrades to withstand only the vacuum of space and its low pressure ( 10⁻⁶ Pascal), but this is not the case. Tardigrades in the same anhydrobiotic state have been subjected to pressures of up to 7.5 gigapascals. This pressure is equivalent to the pressure of rock on your shoulders if you were to descend 180 km into the Earth's mantle!

What happens in the cells of dehydrated tardigrades?

Until now, no one had tried to see what happens inside a tardigrade when it transforms into a "tun."

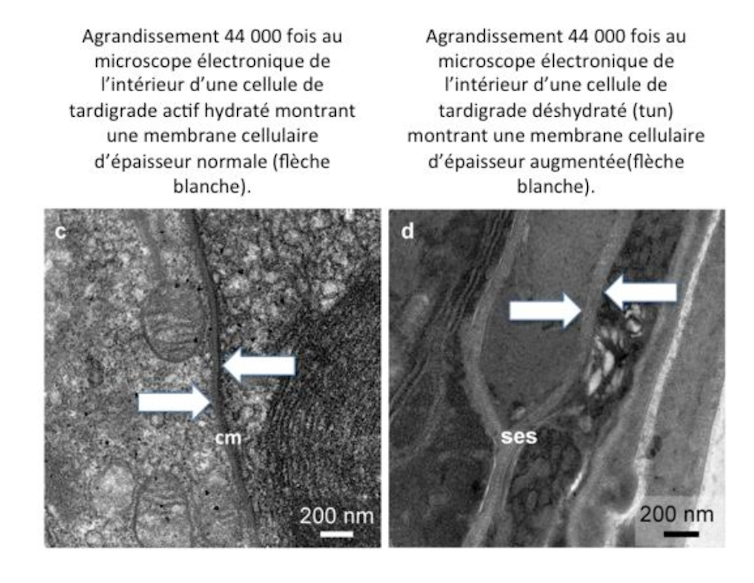

By bringing together two laboratories from the CNRS and the University of Montpellier, we were able to produce images using high-resolution microscopy techniques for the first time. The images collected using transmission electron microscopy allowed us to take a journey inside a tardigrade's anhydrobiote.

An electron microscope uses electrons to illuminate the object being observed and can magnify up to 5 million times, while an optical microscope, which illuminates the object with light (photons), can only magnify up to 2,000 times. Electron microscopes are capable of taking photographs of viruses, for example.

The observation of these images of tardigrades was the subject of a scientific paper published in the international journal Nature Scientific Reports.

Simon Galas, Author provided

It all starts with the animal becoming dehydrated, which leads to the loss of almost all of its water. At the same time, the inside of the tardigrade reorganizes itself and all the structures that make up a tardigrade cell remain unchanged, such as the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, and the mitochondria, which produce the cell's energy. All of the cells appear to be miniaturized versions of the original. This represents an overall miniaturization of the cells by nearly 40%.

Something unexpected appears in the images.

A molecular barrier surrounding all tardigrade cells gradually builds up to a thickness of 100 nanometers in some places. This is very large compared to the membrane that normally surrounds a cell, including in humans. This intercellular barrier, unknown until now, may be the secret to the tardigrade's resistance, allowing it to withstand high pressures that no other living organism could resist. Research into this barrier could perhaps lead to the discovery of new ultra-resistant materials for a future industry that is respectful of the environment.

Simon Galas, Author provided

One clue could explain what this unique defense mechanism is made of. Professor Takekazu Kunieda of the University of Tokyo recently discovered that tardigrades have a special class of proteins that can vitrify dehydrated tardigrades, as demonstrated by a laboratory at the University of North Carolina in the United States.

But what happens to this intercellular barrier when a drop of water is placed on the back of the anhydrobiotic tardigrade? Electron microscope images show that the barrier gradually disappears as the tardigrade emerges from its state of suspended animation, vanishing completely after just 24 hours.

We do not yet know whether this newly discovered protective barrier is produced only by the tardigrade species (Hypsibius exemplaris) raised in our laboratory or by other tardigrade species as well.

Recent data from the sequencing of the first tardigrade genomes has revealed some surprises, such as the presence of a set of genes unknown in other living species, whose functions are only just beginning to be studied by biologists. This discovery sheds further light on the tardigrades' ability to protect themselves against all kinds of attacks and achieve the high levels of resistance for which they are renowned.![]()

Simon Galas, Professor of Genetics and Molecular Biology of Aging, CNRS – Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Montpellier and RICHAUD Myriam, Doctor of Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.