The National Rally through its electorate

Thierry Mariani in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (PACA) region, Sébastien Chenu in Hauts-de-France: the two leaders of the National Rally (RN) party are neck and neck with Les Républicains (LR) candidates Renaud Muselier and Xavier Bertand, ahead of La République en Marche (LREM) and left-wing lists that are struggling to convince voters, according to polls examining voting intentions in these two key regions of France.

Arnaud Huc, University of Montpellier

Beyond its program, elected officials, and controversies, the National Rally is also its voters. However, looking beyond the apparent monolithism of the RN electorate revealed by polls, it is possible to observe the coexistence of several electoral groups.

In the 2017 presidential elections, two main electoral groups shared their RN vote with more specific electorates: electorates with royalist sympathies, practicing Catholics, law enforcement workers, etc.

The two (main) groups within the National Rally discussed here represent a significant proportion of the RN vote and correspond to geographically and ideologically distinct "ideal types." However, they share several common traits: they tend to live in suburban areas, work in the private sector, and generally have a level of education below a bachelor's degree.

Rather than showing these two electorates on maps, we have chosen to show them using statistics and in a roundabout way, i.e., through the sociological characteristics of the populations of municipalities where the RN vote is significant.

Two areas for voting for the National Rally

The municipalities where this vote is significant share certain sociological characteristics. The relationship between these variables and the RN's election results can be measured using tools such as linear regression, principal component analysis, or multilevel analysis. Linear regression can be used to check how the "RN vote" variable changes when other variables, such as the proportion of certain socio-professional categories in the municipality, change.

However, care must be taken not to draw hasty conclusions between certain characteristics of these municipalities and the RN vote. Unlike polls or door-to-door surveys, the tools used do not focus on individuals taken individually but on statistical aggregates. Thus, the relationships measured are not necessarily causal, and certain variables sometimes conceal others.

To illustrate this electoral duality of the RN, we have chosen to study it in the last two "national" elections (the 2017 presidential election and the 2019 European election) and in two regions that have historically been "strongholds" of the RN vote: the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, where the FN vote has been firmly established since the 1980s, and Hauts-de-France, where it has been growing since the 1990s.

In these two regions, there is a very strong correlation (0.945) between the RN vote in the 2017 presidential elections and the 2019 European elections. This means that the municipalities where the RN vote was particularly high in 2017 are also those where the same vote was high in 2019 (the calculations are weighted by the population of the municipalities so that small municipalities are not overrepresented).

These two regions are similar from an electoral point of view, with the RN leading in the first round of voting in 2017. Marine Le Pen came out on top with 27.17% of the votes cast in PACA and even 31.07% (her best result) in Hauts-de-France. Obviously, these are not the only regions where the RN vote is significant, and the study of these territories does not aim to describe the RN vote in all its complexity and entirety.

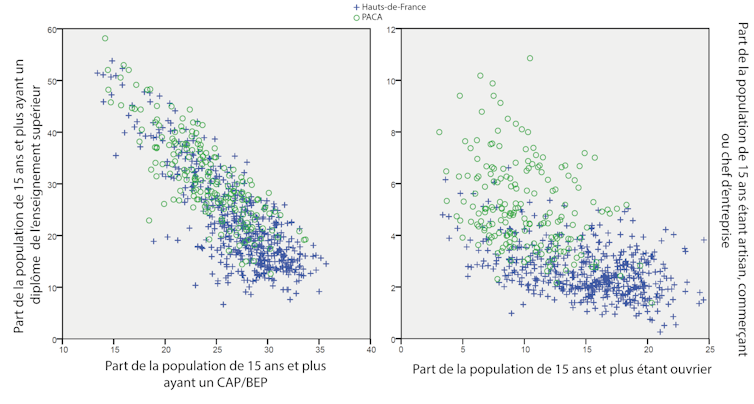

However, in these two regions, the RN's strong results are not found in municipalities with the same sociological characteristics. The RN vote is particularly strong in municipalities with a high percentage of blue-collar workers in Hauts-de-France, while it is weaker in those with a large proportion of artisans, shopkeepers, and business owners. The relationship is rather the opposite in PACA (Figure 1, right).

Similarly, municipalities in the Hauts-de-France region where the RN vote is strong have a higher proportion of residents with a CAP/BEP vocational qualification than in the PACA region, where the overall level of education is higher (Figure 1, left). These differences reflect distinct regional sociological realities, but also indirectly reflect distinct electorates, as highlighted by the interviews conducted as part of my thesis work in each of these areas.

A. Huc, Provided by the author

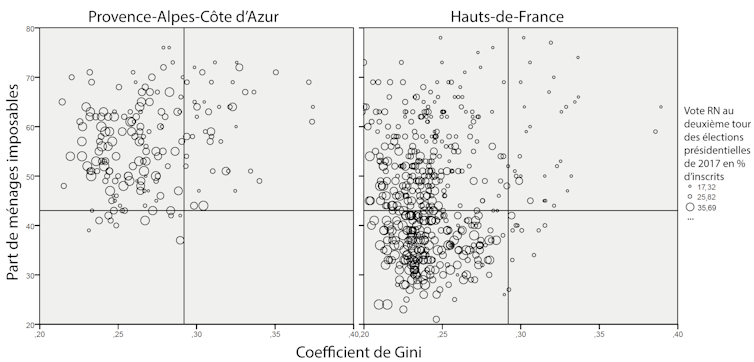

The municipalities where the RN vote is high are not only distinct sociologically, but also "economically." The RN vote is found in municipalities where the rate of taxable households is higher than the national average in PACA, while in Hauts-de-France, it is the poorer municipalities that tend to vote for the RN rather than the richer ones.

However, this should not be seen as a direct contrast between the RN vote among the "rich" in the south and the RN vote among the "poor" in the north (Figure 2). In fact, the RN vote in the south tends to come from the "middle classes," and each of these regions has a diverse range of socioeconomic profiles.

However, there is a socio-economic difference between these electorates. RN voters in PACA are more likely to be artisans, small business owners, and self-employed individuals with average wealth, while in Hauts-de-France, the typical RN voter is more likely to be a blue-collar worker or employee from the working class. Furthermore, municipalities in Hauts-de-France with a level of wealth comparable to those where the RN vote is high in PACA tend to be fairly unfavorable to the RN.

A. Huc, Provided by the author

The duality of the RN

This socioeconomic difference is also reflected in the discourse of RN voters. When interviewed, RN voters in Hauts-de-France are more likely to raise issues such as social inequality, poverty, and even wealth redistribution. These are arguments that are more commonly heard when talking to voters from left-wing parties. Conversely, RN voters in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region are more likely to talk about immigration, excessive taxation, and welfare dependency among certain sections of the population.

This dichotomy is also reflected in the electoral history of RN voters. Some RN voters in Pas-de-Calais consider the RN to be a "working-class" party, and some vote for left-wing parties when the RN is not represented in the second round, rather than for right-wing parties, which are still considered to be parties "for the rich." Conversely, RN voters in the south are more likely to have a history of voting for right-wing parties and are comfortable with the themes and economic programs of right-wing parties.

This is where the duality of the RN lies. This is nothing new, as some polls were already hinting at it in 2013, while the debate on "left-wing Le Penism" and "working-class Le Penism" has been ongoing since 1997.

This party is thus able to mobilize voters whose political, economic, and social concerns are different, even opposed. Paradoxically, many RN voters in the Mediterranean departments are rebelling against those they consider to be "welfare recipients," even though some of the people they consider to be "welfare recipients" also vote for the RN in the northern departments, using social arguments aimed at defending "ordinary people" or increasing the minimum wage or even the RSA (Revenu de Solidarité Active, or Active Solidarity Income).

A. Huc, Provided by the author

This ideological dichotomy is partly reflected in the elected representatives of these territories and adds to a discursive division between elected representatives and activists. Indeed, local officials in the "south" are generally less focused on social issues than those in the "north," who, in turn, are less likely to raise issues related to immigration or taxes during local elections.

This discrepancy was one of the reasons behind Florian Philippot's split in 2017, when he advocated a "neither left nor right" position for the party, including a relatively developed social agenda and very clear opposition to the European Union.

On the other hand, the more "southern" line defended by Gilbert Collard and Marion Maréchal Le Pen aimed more to unite the right and promote ideas compatible with traditional right-wing voters.

Since then, Marion Maréchal (Le Pen) has also taken a step back. Divisive issues (economic and social policy, relations with the European Union) have been pushed into the background. The two wings of the National Rally remain.![]()

Arnaud Huc, Associate Researcher, CEPEL, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.