The RN, from its roots to its establishment: the example of Languedoc

For nearly 40 years now, the far right has been a fixture in the French political landscape. The National Rally (RN) achieved resounding success in the legislative elections on June 12 and 19, winning 89 seats, after Marine Le Pen qualified for the second round of the presidential election on April 10 and 24, 2022, for the second time in a row.

Emmanuel Négrier, University of Montpellier and Julien Audemard

While we have already documented the RN's growing popularity in previous elections, we now feel it is necessary to talk about its"establishment." The difference between the two terms is not simply one of degree, but of nature. While popularity is a matter for voters, establishment is also a matter for elected officials, political machines, and other disseminators of instructions.

The difference between the two lies in who expresses recognition and confirms the legitimacy of the vote. In the first case, it is the voter. In the second, it is the political and institutional offer. And this is precisely what we will show here, focusing on the western Mediterranean coast, which gave the RN all of the seats in two departments, Aude and Pyrénées-Orientales. Seven more seats were added in Gard and Hérault, for a total of 14 out of a possible 22. It is no coincidence that these 14 constituencies crowned the RN. In most of them, Marine Le Pen already had a majority in the second round of the presidential election.

A new development is that there was no differential demobilization of the RN electorate between these two elections. Furthermore, in six cases, RN candidates exceeded the percentage obtained by the Front National candidate on April 24. This progress is due to the extension of its geographical reach from well-known strongholds: the Roussillon plain, the Béziers region, and the Petite-Camargue, where the three outgoing deputies were located.

This deep-rooted support for the RN has conquered new related territories: the Aude valley (the Narbonne-Castelnaudary axis) and its foothills (Limoux); the Roussillon hinterland (Cerdagne, Capcir, and Vallespir); the Gard Rhodanien and the Nîmes hinterland up to the foothills of the Cévennes.

A variety of causes

There are a number of reasons behind the RN vote. For example, we know that the sociological composition of the RN vote in southern France is dominated by citizens from the lower middle class, with few qualifications, many of whom live in suburban housing estates.

It is distinct from that of the north, which is more working class. So the main reason for the RN's legislative success lies in... the relative silence of the working classes, which deprived the NUPES candidates of the support they needed to resist it.

Essentially, therefore, the RN vote in the Midi region does not represent the people in the sense of households identified by their objective social suffering. The latter overwhelmingly abstain, particularly in poor urban neighborhoods where the RN scores its lowest results. This has become more debatable in rural areas (3rd district of Aude,5th district of Hérault), where a vote from employees and workers seems to be emerging in its favor.

In this election, the second major cause is linked to the knock-on effect of the first, and could be described as "ecological" in the sense that the criteria for analysis concern a population rather than individuals.

Due to the recurrence of this high-level voting over 35 years, a political culture has taken shape, which contributes to shaping votes differently, conforming to prevailing opinion, and putting one's own political and family heritage into perspective.

The third explanation lies in the political sphere. The ambivalence or equivalence between the "far left" and the "far right" on the part of many eliminated Renaissance candidates has replaced the idea of a "republican front" with that of individual responsibility for one's choices, all of which are equally valid.

Legitimizing the RN vote

This attitude is reminiscent of the dark days of the Languedoc right wing, which twice allied itself with the National Front (in 1986 and 1998) to prevent a certain Georges Frêche of the Socialist Party from coming to power. The vagueness of the instructions thus led to the legitimization of the RN vote as a vote "like any other," which means that we can no longer speak of electoral roots, but rather of political establishment.

But what is undoubtedly most spectacular about this establishment is that it is not limited to the political right and center. In a region where there were many dissident candidates from the left— Carole Delga, for example—running against NUPES, one might have expected the RN to lose votes between the two rounds wherever the dissident left-wing candidates were eliminated in the first round. However, a reading of the results of these legislative elections in Languedoc-Roussillon shows that the presence of dissident left-wing candidates tended to work against NUPES candidates in relation to their opponents. Should we therefore interpret internal opposition within the left as an additional factor in the RN's strong showing and the institutional recognition of its candidates?

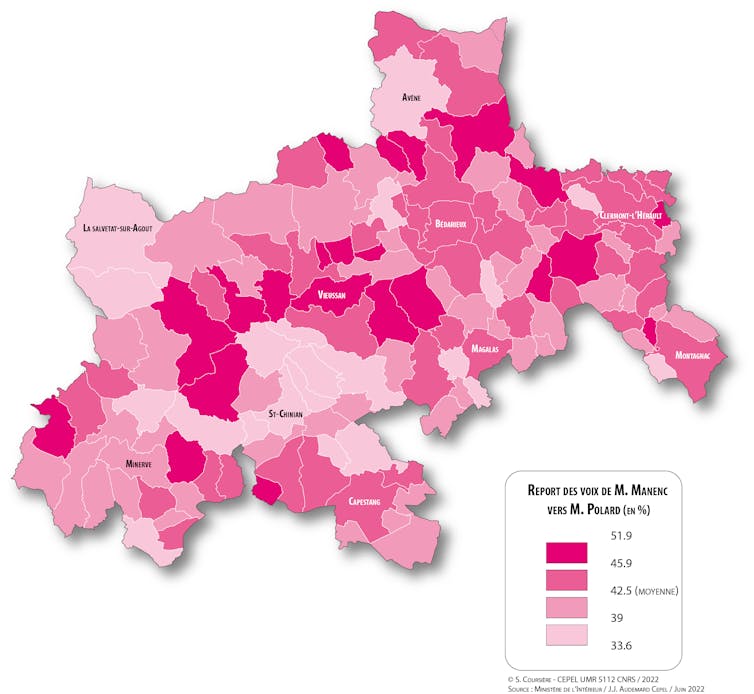

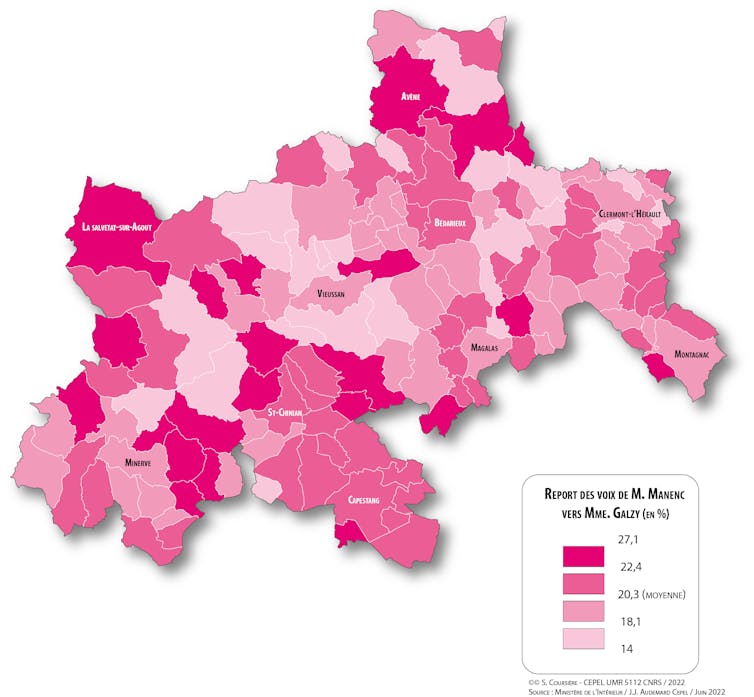

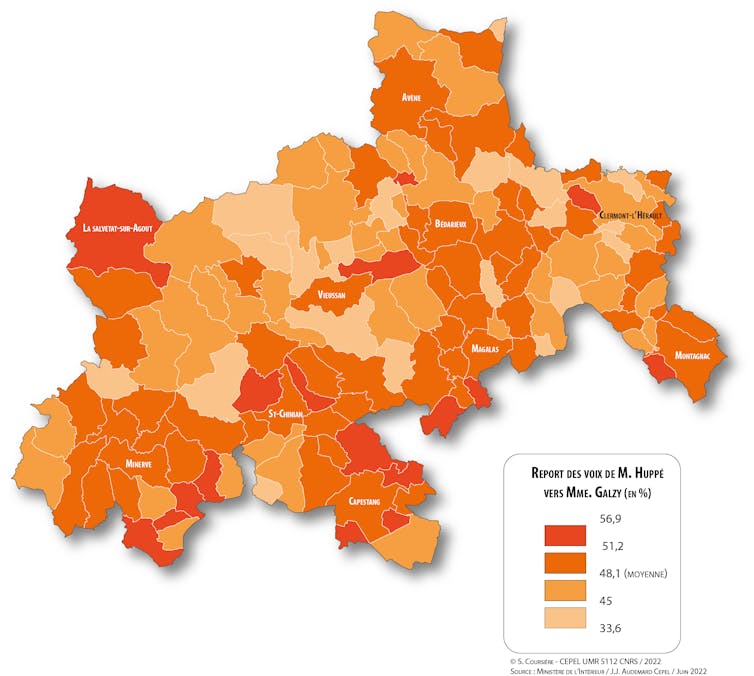

To answer this question, we estimated the transfer of votes between the two rounds of elections in the fifth district of Hérault. This estimate is based on an ecological inference model, which allows individual statistical relationships to be calculated from aggregated data.

The various delays were estimated at the level of polling stations within the district. The figures presented in the maps and text below correspond to the averages of these values, shown for clarity at the level of municipalities or the district as a whole.

When a left-wing municipality swings to the right

Our decision to focus on the fifth district of Hérault is justified by a number of criteria. Historically the most left-wing district in the department, it was represented from 2002 to 2017 by the president of the departmental council, Kléber Mesquida, whose hegemonic position could be threatened by the election of the FI candidate under the Nupes banner, Pierre Polard.

Unsurprisingly, the dissident left-wing candidate (RDG), Aurélien Manenc, achieved the highest score among the other dissident candidates in the department in the first round (15.7%), just behind the outgoing deputy from the presidential majority, Philippe Huppé (17.1%). Pierre Polard managed to make it through to the second round with 24.3% of the vote, behind the RN candidate, Stéphanie Galzy (28.1%). In the second round, with no increase in voter turnout (50.6% in the first round, 50.5% in the second), a rather unusual situation for a predominantly rural constituency, the RN candidate won with 54.2% of the vote.

E. Négrier, J. Audemard, Provided by the author

E. Négrier, J. Audemard, Provided by the author

E. Négrier, J. Audemard, Provided by the author

Our three maps show the geographical distribution, at the municipal level within the district, of the estimated transfer of votes from A. Manenc's supporters to P. Polard and S. Galzy, as well as those from P. Huppé's supporters to S. Galzy.

Two factors to understand deferrals

The victory of the RN candidate can thus be interpreted as the result of two factors.

Firstly, the imperfect transfer of votes from the dissident candidate to the NUPES representative, estimated at an average of 42.5% within the constituency. Secondly, the significant transfer of votes she received from the Renaissance electorate (48.1%), which is particularly right-wing in a constituency where the LR candidate obtained only 2.8% of the votes in the first round and where the Reconquête! candidate did not exceed 5% (4.3%).

But it is also interesting to note that the estimated transfers from the RDG candidate to the RN candidate are not insignificant either (20.3% on average). It is difficult not to interpret these results as the consequence, in addition to the socio-territorial specificities of the constituency, of the hesitation of the president of the departmental council to call for a vote in favor of the NUPES candidate. In this context, the RN candidate, now elected, has in fact benefited from institutional recognition, at least by default.

Another result suggested by our model's estimates, which we will only cite here in terms of figures, concerns the differential volatility of the NUPES and RN electorates in this constituency.

While the RN candidate appears to retain an average of nearly 80% of her electorate from one round of elections to the next, the Nupes candidate only retains 62.7% of his first-round electorate, with nearly a third (27.8%) abstaining in the second round. While this gap is undoubtedly due, once again, to local context – 75% of Pierre Polard's electorate maintains its vote in the second round in Capestang, the municipality where he is mayor, as well as in the surrounding municipalities – it can be analyzed as further evidence of the RN vote's deep roots in the constituency.

While they must be understood in light of the specific sociopolitical characteristics of the former Languedoc-Roussillon region, the results presented here are undoubtedly indicative of a broader phenomenon of accelerated legitimization of the RN within the French political landscape, through both the consolidation of its voter base and its de facto recognition as a mainstream option by other players in the electoral arena.![]()

Emmanuel Négrier, CNRS Research Director in Political Science at CEPEL, University of Montpellier, University of Montpellier and Julien Audemard, Associate Research Scientist

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.