The species jump: when an animal virus causes the emergence of a human disease

As we all know, the world population is currently being shaken by a new virus responsible for a pandemic: SARS-CoV-2. Capable of efficient transmission, this virus has rapidly overwhelmed healthcare systems unprepared for such a threat. Due to its sudden appearance, this new virus is described as "emerging."

This article was written by students in the Master's 1 program in Microorganism-Host-Environment Interactions at the University of Montpellier (class of 2019-2020), supervised by Jean-Christophe Avarre, Research Institute for Development (IRD), and Anne-Sophie Gosselin-Grenet, University of Montpellier.![]()

In virology, an emerging virus is an agent that has been newly observed in a given population. Of animal origin, this virus has triggered an epidemic in humans, as is the case with other viruses (influenza viruses and Ebola viruses, for example). This phenomenon, which allows an animal virus to infect humans and multiply in them, is linked to a mechanism called "species jump."

What is a virus? How does it work?

Viruses are microscopic biological entities that are widespread in the environment and play an essential role in the evolution and regulation of the populations of organisms they infect.

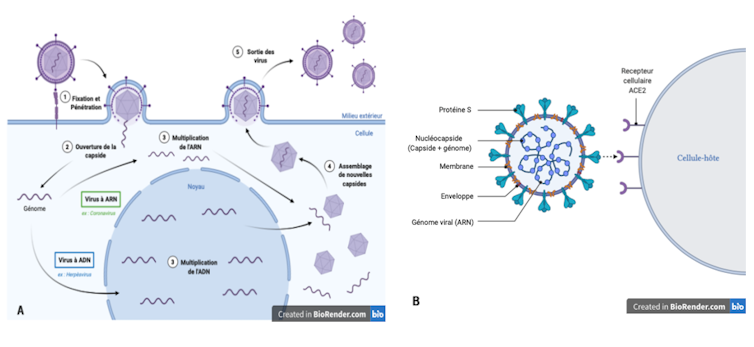

A virus consists of a genome (its genetic information), a protein shell called a capsid, which protects this genome, and sometimes an envelope. A virus is not capable of multiplying on its own; it must infect a cell in order to hijack the raw materials and machinery it needs to manufacture its own components.

Author provided

Tropism and species specificity: major viral characteristics

Infection begins when a virus encounters a cell. This encounter is initiated by proteins on the surface of the virus that recognize a specific cellular molecule, called a receptor, exposed on the surface of the cell. This recognition, which depends on the quantity and type of receptors present on the cell, determines the cell's sensitivity to a virus. It is essential for the virus to attach itself to the cell and then penetrate it. The virus's replication will then depend on the cell's permissiveness, i.e., its ability to allow the production of new viral particles.

The two parameters, sensitivity and permissiveness, thus define the cellular tropism of the virus, in other words its ability to penetrate and multiply preferentially in a particular type of cell.

The cells of an organism have their own sensitivity and permissiveness to a virus, which also differ from one species to another. The cellular tropism of the virus therefore also contributes to the virus's host range, i.e., the specificity of the species it is capable of infecting and in which it can multiply. Thus, some viruses have a broad host range, while others are only capable of infecting a single host species.

Species specificity therefore implies a species barrier that prevents viruses (and pathogens in general) from passing from one species to another and thus prevents the inter-species transmission of associated viral diseases. This barrier is multifactorial, involving physical, chemical, molecular, metabolic, and immunological factors.

Crossing a species barrier leading to viral emergence

Viral emergence can manifest itself in different ways: it can be emergence in a new territory, linked to a change in the distribution area of the virus or its host, or emergence of a disease in a new host species, linked to a structural change in the virus that allows it to infect that species.

Many viral outbreaks originate from the transmission of viruses from animals to humans: these are known as zoonotic diseases or zoonoses, as was the case with AIDS, which resulted from the transmission of a virus from monkeys to humans, or SARS in 2003, which resulted from the transmission of a coronavirus from bats to humans. This inter-species transmission, or species jump, implies that the virus is capable of crossing the species barrier.

Author provided

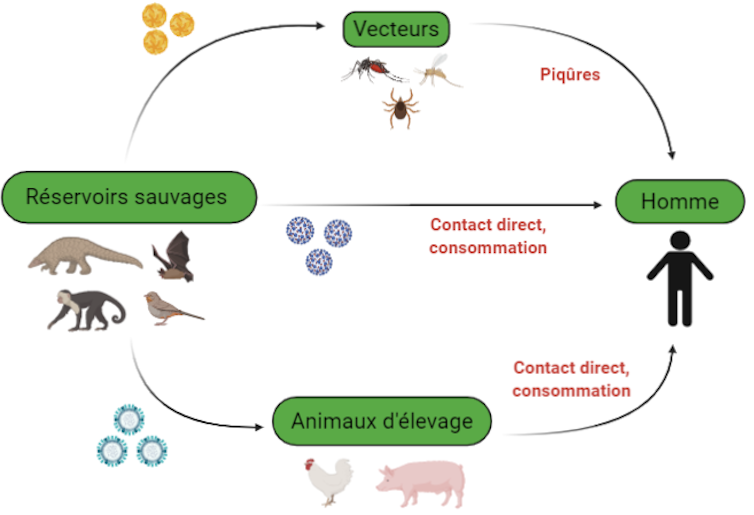

This species jump requires close contact between an animal species infected with a virus, known as a reservoir, and humans. The virus is generally non-pathogenic to the reservoir, and they have coexisted for a long time. Viral replication is thus maintained in the reservoir, and numerous viral particles can be produced without harming it.

The virus is transmitted from the reservoir to humans either directly, particularly through the ingestion of contaminated raw food or through bites, or indirectly through vectors. These vectors are often arthropods, such as mosquitoes, which carry viruses between different hosts during their blood meals.

Since the virus and the new host species have only recently begun coexisting, species jumping may be responsible for the emergence of viral diseases, as is currently the case with COVID-19.

How can the leap of species occur?

For a species jump to be successful, the virus must complete four steps: come into contact with the new host species (in this case, humans), infect its cells and multiply within them, evade the host's defenses, and spread within the population of this new host.

Contact is facilitated by increased promiscuity between humans and animals, resulting in particular from the expansion of cities, the destruction of ecosystems (deforestation), and the illegal trade in wildlife.

Proximity is not everything, however, and the virus must undergo certain changes in order to survive inside its new host. The virus must be able to attach itself to receptors on the surface of its new host's cells in order to penetrate them and multiply by hijacking the cell's machinery. This ability to adapt is partly due to their very high mutation rate. The mechanism of viral genetic material multiplication makes many errors that are not repaired by the "proofreading" systems common to living beings. These mutations can lead to structural changes in the virus's surface proteins, allowing it to attach to new types of cells and thus modifying its cellular tropism. These mutations can also enable the virus to multiply in the cells of the new host species.

The virus, exposed to the host's defenses (its immune system), will also have to develop escape strategies. To do this, some viruses directly attack the host's defense cells, such as HIV, while others "hide" by infecting cells that are inaccessible to the immune system, or even scramble the danger signals between the cells of the host organism.

Finally, in order to spread among the population of the new host, the virus must be transmitted between individualsvia respiratory droplets, blood, sexual contact, or even simple direct contact between individuals. The strategy and effectiveness of the mode of transmission will then determine the virus's ability to spread and persist in the new species. Various factors related to the infected host can also influence the effectiveness of transmission. For example, once established in the new host, the virus can take advantage of its movements to spread. Through the movement of human populations linked to globalization, trade, and travel, the virus can then infect individuals in another region and thus expand its range. If the spread remains localized, it is referred to as an epidemic, but if it spreads globally, it is referred to as a pandemic. In cases where transmission is not possible between different individuals of the species, this is referred to as transmission leading to an epidemiological dead end.

Through its considerable impact on the environment—deforestation, poaching, and intensive farming—coupled with ever-increasing globalization, humans have become a major contributor to the emergence of viral diseases, unwittingly facilitating species jumps that would normally be accidental.

Jean-Christophe Avarre, Researcher in viral ecology, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Anne-Sophie Gosselin-Grenet, Senior Lecturer in Virology, UMR Diversity, Genomes and Microorganism-Insect Interactions (DGIMI), University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.