Metropolitan voting and its divisions: the example of Montpellier

How can we interpret the map of municipalities that put Jean-Luc Mélenchon in the lead in the first round of the presidential election? The strong results achieved by the Insoumis candidate, particularly in working-class neighborhoods— for example, 93% in Seine-Saint-Denis and other regions —raise questions about how large cities reacted to the elections and illustrate a deep political divide that civic and political action can analyze.

Emmanuel Négrier, University of Montpellier; Jean-Paul Volle, University of Montpellier; Julien Audemard and Stéphane Coursière, University of Montpellier

Thus, a city like Montpellier has established itself as the leading metropolis in France in terms of votes for Jean-Luc Mélenchon. The candidate for La France Insoumise obtained 40.7% of the votes cast there. By way of comparison, in the other cities where he came out on top, Jean-Luc Mélenchon achieved 31.1% in Marseille, 33.1% in Nantes, 35.5% in Strasbourg, 36.9% in Toulouse, and 40.5% in Lille, the only other city where his score was close to that achieved in Montpellier.

The sociological identity of the city

Mélenchon's vote can be explained first and foremost by the sociological identity of the city of Montpellier, with a poverty rate of 27% according to INSEE in 2019, nearly double the national average, which resonates with the social dimension championed by the candidate.

Author provided

This observation is reinforced when examining the votes bureau by bureau. While it is true that voters in working-class neighborhoods voted less than average—there are sometimes differences of 20 points between the neighborhoods where people vote the least and the more affluent neighborhoods where people vote the most—their turnout exceeded expectations, with participation exceeding 50% in most cases.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon dominates in these neighborhoods. For example, he won 77% of the vote in the iconic Petit Bard neighborhood, with a turnout of 63%. This initial observation is reinforced by the unexpected continued support of young voters during this election. Considering Jean-Luc Mélenchon's considerable share of the 18-34 age group vote, it is logical to conclude that he is in a position of strength in the young capital of the Hérault department.

Effective mediation work

However, these variables are not specific to Montpellier and do not fully explain the increased support for him. On the one hand, neighborhoods covered by urban policy were the focus of intense mobilization efforts during this campaign. The proximity between a lived experience and a program is not automatic. To transform this into motivation, a whole process of mediation, particularly at the local level, must be developed, which has borne fruit here.

Secondly, it should be noted that Mélenchon's campaign, beyond its work in neighborhoods, relied on considerable resources: in addition to the rally at the Arena in Montpellier on February 13, 2022 (attended by approximately 8,000 people), there was a significant physical and symbolic presence in public spaces.

This hyper-presence has legitimized in Montpellier, perhaps more obviously than elsewhere, the path of "useful" voting for a left-wing electorate that is much more diverse than the label and program of La France Insoumise would suggest. With 40.7% of the vote on April 10, 2022, he almost matched the total number of left-wing votes in the 2017 presidential election. Although the mayor, Michael Delafosse, had thrown his support behind Anne Hidalgo, she only won 2.3% of the vote, which was better than her national average but still disastrous.

Another reality in the Hérault region

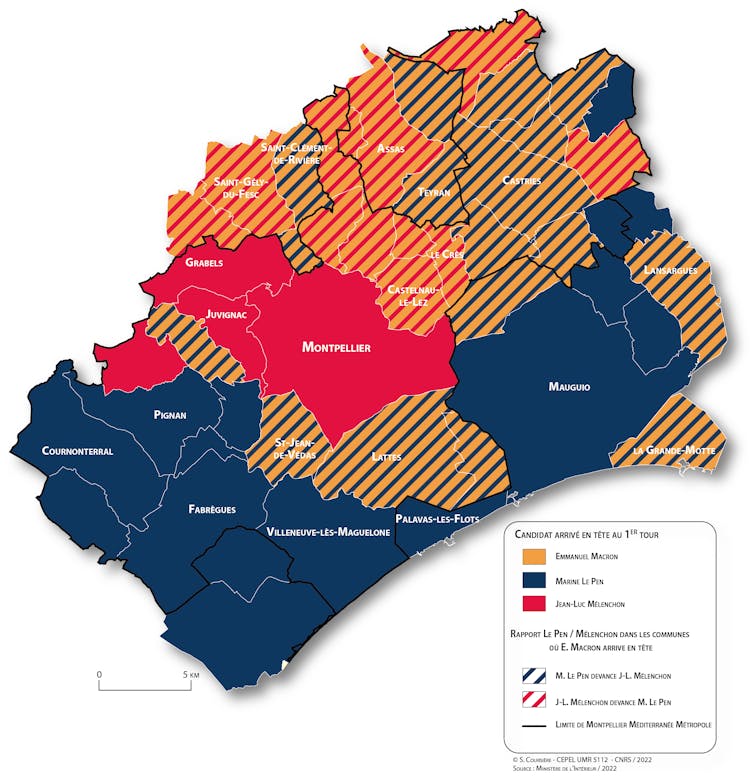

But the map shows us another reality, beyond the boundaries of the city of Montpellier. Still in the Hérault department, Jean-Luc Mélenchon also came out on top in three nearby towns: Grabels, whose mayor René Revol is a long-time supporter of the candidate, and where he achieved nearly 30% of the vote; Juvignac, a town that has long been typical of a national vote, where a new population of young tenants has recently settled; Murviel-lès-Montpellier, more remote, governed by an environmentalist left, and marked by significant struggles in this regard in the past and more recently.

Sociologically speaking, we are not here in the heart of LFI's urban, young, and working-class target audience.

Three factors are at play in the Mélenchon phenomenon: the widespread tactical voting of the left in his favor; the existence of objective conditions that make the path more obvious than elsewhere; and the mobilization of grassroots activists.

These factors also explain why Mélenchon's vote appears fairly consistent across social classes. This is the main difference with Le Pen's vote. His penetration into the upper classes, which can be seen in his success in certain affluent neighborhoods of Montpellier, is matched by his strong impact in working-class neighborhoods and even in municipalities far from the capital, as can be seen on the map to the north. Three territories, three sociologies that explain the electoral success of Jean-Luc Mélenchon's LFI.

A clear electoral geography

Three territories, this time for three candidates, is also what the map of the leading candidates in the municipalities of the Montpellier urban area shows. Alongside the Mélenchon vote, the Macron and Le Pen votes paint a clear electoral picture, to say the least.

The President of the Republic thus came out on top in almost all of the municipalities in the immediate suburbs of Montpellier and further north. Marine Le Pen's strongholds are mainly in the south and east of the city, in the municipalities along the Mediterranean coast. These municipalities are mainly home to an elderly electorate of small property owners, where right-wing voting, and in particular voting for the National Rally, is deeply rooted. The correlation between Marine Le Pen's scores in the first round of the 2017 and 2022 presidential elections at the municipal level in the Montpellier urban area is very high (R=0.90), revealing the great stability of the far-right candidate's strongholds.

In contrast, within the municipalities of the inner suburbs, there is a mix of wealthy, long-established homeowners and a younger electorate living in recently built collective housing to meet the demographic expansion of the metropolis.

An internal divide within these municipalities

The profile of these electorates corresponds well with what we know about the sociology of Macron voters. Analysis of the map also reveals an internal divide within these municipalities. While the towns located north of Montpellier, in its immediate suburbs, placed Jean-Luc Mélenchon in second place, Marine Le Pen overtook him as we moved further away from the regional capital.

These areas overlap with the influx of first-time buyers who can no longer afford to live in the capital or its inner suburbs.

Behind this divide, we can also see the influence of local political trends. Emmanuel Macron achieved high scores in municipalities that have long been governed by the right, such as Castelnau-le-Lez—a town where the former mayor, LR senator Jean-Pierre Grand, spoke out in his favor.

La Grande-Motte, a town where Mayor Stéphan Rossignol is president of the LR federation of Hérault and a supporter of Valérie Pécresse, is the only town on the Montpellier coast where the outgoing president is ahead of Marine Le Pen. Like Jean-Luc Mélenchon on the left, Emmanuel Macron is undoubtedly benefiting from the "useful" vote on the right: the correlation between his scores and those of François Fillon in the first round of the last presidential election seems to confirm this idea (R=0.55).

Although he remains weak in Montpellier, Emmanuel Macron is nevertheless benefiting from the reconfiguration of the right-wing vote to make gains among voters in Montpellier's affluent suburbs. Of the three leading candidates, he is the one whose scores are improving in the largest number of towns in the Montpellier urban area.

Our dual social and political focus therefore allows us to invalidate two complacent theories about urban voting: that left-wing and right-wing populism are equally popular among the same electorate, and that peripheral voting is geographically homogeneous.

If we see that Mélenchon's vote does not occupy the same strongholds as Le Pen's vote, it is because they are sociologically and politically distinct.

The other lesson, valid in Montpellier as in other cities, is the huge gap between national policy and regional policy, which is essentially governed by parties in disarray.![]()

Emmanuel Négrier, CNRS Research Director in Political Science at CEPEL, University of Montpellier, University of Montpellier; Jean-Paul Volle, Professor Emeritus, University of Montpellier; Julien Audemard, Associate Research Scientist, and Stéphane Coursière, Research Engineer, Cartographer, CEPEL, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.