Are consumers willing to eat products made from food waste?

New entrepreneurial ventures are emerging to turn edible waste into snack foods and prepared meals. A study of 941 French consumers questions the acceptability of this food upcycling.

Marie-Christine Lichtlé, University of Montpellier; Anne Mione, University of Montpellier; Béatrice Siadou-Martin, University of Montpellier and Jean-Marc Ferrandi, Nantes University

Companies offeringfoodupcycling, overcycling, or recovery are on the rise. Hubcycled produces flour from soy milk and flavoring from strawberry seeds, the Ouro biscuit factory recycles spent grain into appetizer crackers, and In Extremis recycles unsold bread from bakeries into appetizer crackers.

Foodupcycling is defined as food in which at least one of the ingredients is either a by-product or residue from the manufacture of another product (spent grain for beer), an unsold product (bread), or an ingredient that was previously considered waste and/or wasted in the supply chain.

Due to the costs associated with collecting this waste or unsold goods and processing them, the retail price of these upcycled products is higher than that of traditional offerings. But what about consumer acceptance of these products? Are consumers willing to make this financial sacrifice in order to switch to sustainable food products? Can this niche model become a sustainable business model? These are the questions we answer in a survey of 941 consumers.

Food upcycling

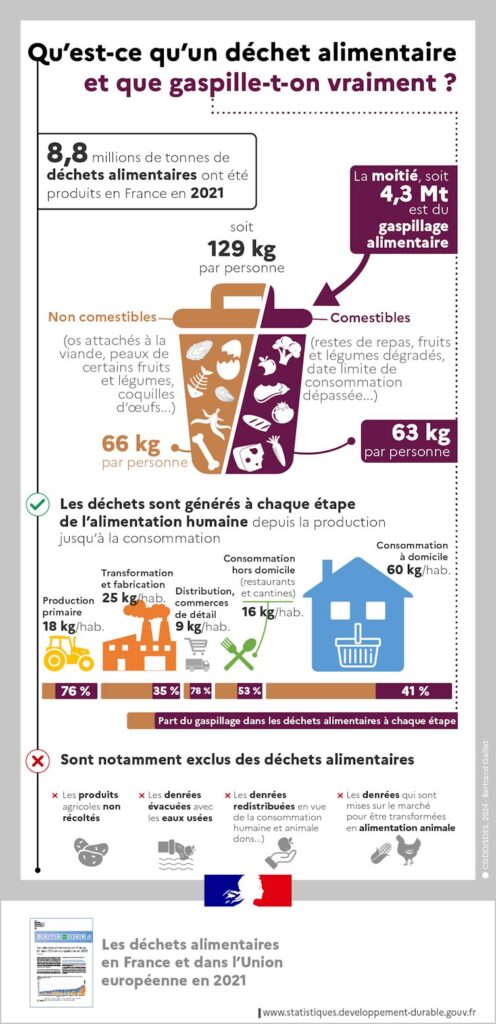

In 2021, 8.8 million tons of food waste were produced in France. Of this waste, 4.3 million tons are edible—unconsumed food still in its packaging, leftovers, etc. To encourage companies to transition their production models towards greater environmental sustainability, in 2020 the government passed the Anti-Waste Law for a Circular Economy (Agec). The agri-food industry faces significant challenges: ensuring food security, offering sustainable products, and limiting food waste at all levels, whether in production, distribution, or consumption.

Acceptability ofupcycling

Our objective is to measure the acceptability of upcycled products and identify the attributes that are likely to increase this acceptability—whether they relate to the company, the quality of the product, or the manufacturing process.

Every Monday, useful information for your career and everything related to company life (strategy, HR marketing, finance, etc.).

To measure consumer acceptance of these upcycled products, our research is based on an experiment conducted with 941 consumers. After reviewing an offer of snack crackers—price, weight, product appearance, labeling—consumers were surveyed four times. The data collected allows us to assess consumer behavior, as reflected in their attitude toward the product and their willingness to pay, initially based on a minimal presentation of the offer.

Information is also provided and communicated on three different potential benefits: the company's virtuous approach, the taste quality, and the procedural quality of the cookies.

Willingness to pay

Our research has three main findings. The first concerns willingness to pay. On average, consumers indicate a willingness to pay €1.96. This price is well above the market reference price (the market leader offers the product at €0.90). However, it remains below the actual cost of this offer or of high-quality offers (some organic brands are sold for more than €3).

Secondly, adding an argument, regardless of its nature, improves the value created. Consumers are then willing to pay an average of €2.15 instead of €1.96 (a gain of around 10%). However, adding one or two additional arguments does not improve willingness to pay.

This new product is not accepted in the same way by all consumers, which justifies the implementation of a differentiated approach. Psychological distance influences the perception and representation of the upcycled product. It is defined by construct level theory as a subjective experience associated with the degree of proximity or distance that an individual feels towards an object, in this case the cookie. We show that psychological distance explains attitudes toward the product and willingness to pay. In other words, consumers who are less distant from the cookie have a higher willingness to pay than those who are distant and have the most favorable attitude. Conversely, those who are most distant from the cookie have the lowest willingness to pay and the most unfavorable attitude.

Communicating uniqueness

This research therefore suggests ways to improve the sustainability of this business model. In terms of communication, it is important for companies operating in this market to add a benefit that is consistent with the upcycled nature of their products and to communicate this benefit. The aim of this communication is to strengthen the credibility of companies in this market. It must be based on concrete arguments in order to reduce the psychological distance.

There is no point in multiplying the benefits, as these communication efforts do not necessarily improve willingness to pay and attitudes. This result is consistent with the limited effects shown by the multi-labeling of food products. Studies show that having multiple labels or certifications does not improve willingness to pay for food products such as honey.

Companies must clearly target consumers who are sensitive to food waste and position themselves in this niche market before they can hope to reach all consumers. This segmentation makes it possible to offer differentiated educational approaches tailored to different audiences in order to reduce their psychological distance from cookies and convince them to buy this product with a higher willingness to pay.

Marie Eppe, founder of In Extremis, contributed to this article.

Marie-Christine Lichtlé, University Professor, Co-Director of the MARÉSON Chair, University of Montpellier; Anne Mione, Professor of Strategic Marketing, Quality Management, and Strategy, University of Montpellier; Béatrice Siadou-Martin, University Professor in Management Sciences, Co-Director of the MARESON Chair, University of Montpellier and Jean-Marc Ferrandi, Professor of Marketing and Innovation at Oniris, University of Nantes, Co-founder of the MARÉSON Chair, Nantes University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.