Mnemons: when memory depends on prion proteins

Just as we are able to memorize information, single-celled organisms can retain memories of past stress. This allows these simple cells to respond better to the same stress in the future—and thus, for example, ensure the survival of the colony.

Fabrice Caudron, University of Montpellier

But how are these memories formed at the molecular level? Can these mechanisms teach us more about the very foundations of memory in humans? Could they even help us better understand the mechanisms of certain diseases?

To find out more, we looked at a memorization process found in baker's yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Here are the results of our work, just published in the journal Current Biology.

Sex and memory in baker's yeast

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a fairly simple organism: consisting of a single cell with a nucleus (like human cells and unlike bacteria), it reproduces vegetatively, meaning that its cell forms a bud on the surface that will become the future daughter cell.

However, S. cerevisiae can also reproduce sexually. In order to identify a potential sexual partner, yeasts secrete and detect specific chemicals: sex pheromones. When two yeasts of opposite sexes are in close proximity, they stop vegetative reproduction and grow a cytoplasmic projection (cytoplasm being the "body" of the cell, the part that surrounds the nucleus), called a "shmoo," toward their counterpart.

Since yeast cells cannot move, they elongate toward each other until they meet and fuse into a new individual in which their genomes are mixed. This increases their genetic diversity.

But this commitment to sexual reproduction is a costly, if not risky, decision. For example, imagine that two cells of the same sex court a single cell of the opposite sex. One of these two cells will not be able to fuse with its prospective partner and will therefore have produced a shmoo for nothing... Fortunately, yeasts can "choose" not to respond to the pheromone—a refusal that they will then remember for a long time.

Once a yeast cell stops responding to pheromones, it remains that way for the rest of its life. It will then only reproduce vegetatively. However, its future daughter cells will be born "naive": they do not inherit their mother's memory and are capable of responding to any sex pheromones present in their environment.

How does the memory of a single-celled organism work?

The key to S. cerevisiae memory is the Whi3 protein. By changing its conformation (the way it folds in three dimensions), Whi3 becomes inactive, allowing the cell to ignore the pheromone.

We observed that this Whi3 protein behaves somewhat like a prion —a protein that is pathogenic due to its abnormal 3D folding, and often contagious. Prion-like proteins were identified in the 1980s by American neurologist Stanley Prusiner, particularly in the wake of the mad cow disease crisis: he demonstrated that by changing its three-dimensional conformation, the prion protein becomes pathogenic and contagious, causing not only disease in cattle, but also Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans.

Returning to yeast, the change in Whi3 conformation is self-replicating, meaning that it is transmitted from an abnormal protein to a normal protein (which it "contaminates") through simple contact, forming aggregates. This self-replicating phenomenon for encoding memory is interesting because it implies that the new conformation of its Whi3 protein can be recorded over time by being transmitted and remain stable.

However, a significant problem remains: how can the parent cell ensure that its "memory" does not invade its daughter cell?

Understanding this form of physical memory

It is important to note that yeast harbors many types of prion proteins, most of which, once formed, are transmitted to the daughter cell. However, this is not the case with Whi3, which makes it unique.

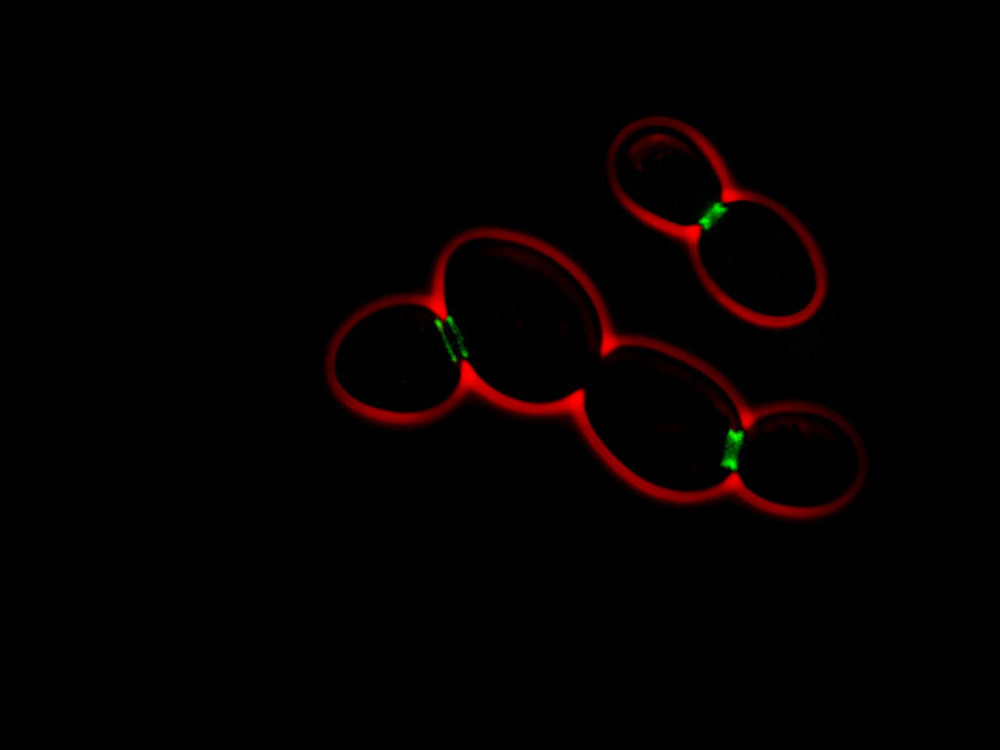

Using yeast genetics and microscopy, we compared the best-understood yeast prion, named Sup35 (the translation termination factor), with Whi3.

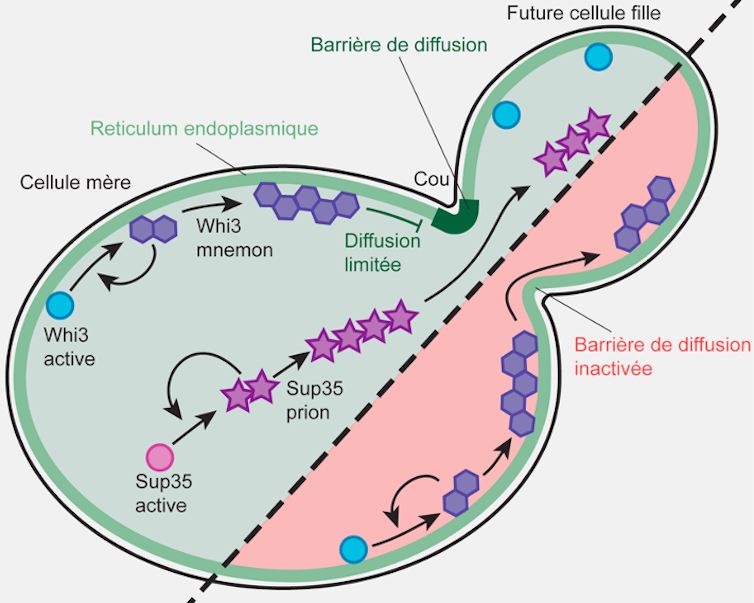

We have already discovered that Whi3 binds to the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (a huge network of sacs where the cell assembles its proteins). But we have also discovered that barriers are set up within this reticulum between the mother cell and the elements of its future daughter cell, thereby allowing the retention of Whi3 from the parent cell.

Genetic removal of diffusion barriers causes Whi3 to transform into a "true" prion, which can spread to daughter cells. The confinement of Whi3 and the memory encoded by this protein are lost. However, the spread of the Sup35 prion, which does not bind specifically to the endoplasmic reticulum, is not affected by the diffusion barrier.

Fabrice Caudron, Provided by the author

A step toward better understanding cellular memory

This study highlights that the association of prion-like proteins with membranes, together with the compartmentalization of these membranes by diffusion barriers, constitutes a powerful mechanism for the formation of long-term epigenetic cellular memories (i.e., memories not linked to information encoded in DNA). These "memories" can be confined to a subcompartment of the cell, in this case the dividing mother cell.

The Whi3 protein, although very similar to prions, is therefore considered a "mnemon": a particular type of prion kept under control that encodes memory. But ultimately... what does this have to do with neural memory, the kind that operates in our brains?

It turns out that a protein important for neuronal memory, for example during the memorization of sexual disappointments in Drosophila flies, depends on the prion-like behavior of the CPEB protein in the synapse, the connection between two neurons.

We hypothesize that in Drosophila, CPEB is also a mnemon, confined to the synapse activated during memory formation. This confinement would prevent the CPEB protein from diffusing into neighboring synapses of the same neuron (which could activate them erratically and compromise memory).

In Homo sapiens, the CPEB3 protein has the same characteristics as CPEB in Drosophila: it can behave like a prion, or more likely, a mnemon. These similarities imply that the basis of memory, at the cellular level, has a long history in evolution...

These findings and hypotheses raise the question of whether neurodegenerative diseases associated with prions and protein aggregates are sometimes caused by defects in cellular confinement. We know, for example, that these barriers are less effective in the stem cells of aged mice. Could we then try to restore them in order to limit the spread of prion-like proteins?

A theory that is still theoretical, but which opens up many possibilities...![]()

Caudron Fabrice, Team Leader, Cell Biology, Yeast Genetics, Asymmetric Cell Division, Cell Memory, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.