Rays and sharks hit hard by the last mass extinction 66 million years ago

The last mass extinction to affect the evolution of life occurred 66 million years ago (Ma), marking the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene periods. While this biological crisis is known to have caused dramatic extinctions globally and wiped out large groups of vertebrates such as dinosaurs, the consequences of this extinction on marine biodiversity are still the subject of intense debate. We have just published a study in the journal Science looking at the impact of this crisis on the diversity of elasmobranchs (sharks and rays), a major group of marine vertebrates that survived this mass extinction. Our work indicates that this crisis was brutal and that it affected elasmobranchs in a heterogeneous manner, both in terms of the groups affected and the geographical distribution of species.

Guillaume Guinot, University of Montpellier

Previous estimates suggest that this crisis wiped out more than 40% of genera and 55 to 76% of species. However, a growing body of evidence indicates that the magnitude of this event varied among groups, ecologies (e.g., diets, lifestyles), and geographic areas.

However, overall estimates of biodiversity loss during this period have been mainly extrapolated from data on marine invertebrate groups, which alone cannot reflect the complexity of extinction patterns during this crisis. Marine vertebrates, due to their higher position in the food chain, could therefore provide new information about this extinction and the post-extinction recovery of fauna. But these groups must have survived!

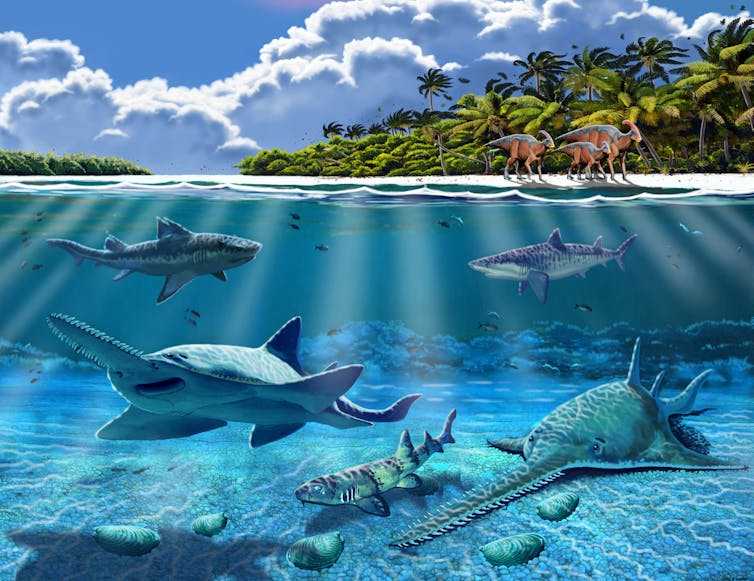

Among these marine vertebrates, elasmobranchs are an iconic group of predators that already represented an important component of marine ecosystems in the Cretaceous period and had developed a wide range of ecologies. Belonging to the class of cartilaginous fish (chondrichthyans), these organisms have a skeleton that rarely fossilizes. However, they are represented by an abundant fossil record, mainly composed of teeth that they lose and replace throughout their lives and whose morphology allows species to be identified. Thus, due to the quality of their fossil record, their presence before and after the extinction event, and their position at the top of the food chain, sharks and rays are a very good case study for analyzing the impact of this crisis on marine vertebrates.

Using fossil data, our goal was to accurately quantify the extent of the extinction, the profile of the victims and survivors, and the consequences of this crisis on the evolution of shark and ray fauna after the extinction.

Over ten years of data compilation

We first compiled all the fossil record data for all elasmobranch species over a time interval of approximately 40 million years (from -93.9 to -56 Ma), including the extinction event. This lengthy task took more than a decade and involved compiling an inventory of shark and ray species present during the Late Cretaceous–Paleocene interval, as well as their occurrences: all instances where fossils have been found for each of these species. This information is available in a disparate manner in several hundred scientific papers published from the19thcentury to the present day, and had to be compiled.

A species can therefore have several occurrences, and each occurrence corresponds to a distinct age and geographical coordinates. We were able to inventory more than 3,200 occurrences for 675 fossil species, but we had to verify the identifications and geological ages attributed to each of these occurrences in the scientific literature. Indeed, species classification (taxonomy) is a constantly evolving discipline, and it was first necessary to update the classification of each species and sometimes correct erroneous identifications. In addition, the ages of the geological formations that yielded the fossils may also be reevaluated by new studies, and this information had to be updated. This tedious but crucial expert work forms the basis of the analyses we conducted for this study.

Once the data had been compiled, we used statistical models to estimate the ages of appearance and extinction for each of the 675 species. This laborious analytical work is essential because the fossil record contains a number of preservation and sampling biases. We must therefore first take into account the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the fossil record in order to estimate the lifespan of fossil species. These models, in which Fabien Condamine (co-author of the study) is also a specialist, can then be used to estimate the rates of speciation and extinction (number of extinctions or appearances per million years per species) for the group studied.

Sharks and rays have not been affected in the same way

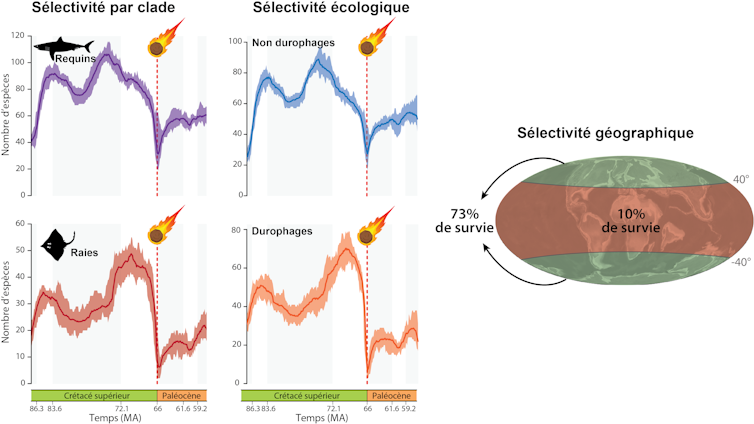

Our results show, with high resolution, that 62% of elasmobranch species disappeared during this crisis and that this extinction was "abrupt" on a geological timescale, as it was confined to a period of 800,000 years.

But were different groups of elasmobranchs affected equally by this extinction? To answer this question, we assessed extinction rates among sharks and rays, and among different groups of sharks and rays. Our results indicate that rays were more severely affected than sharks (72.6% extinction versus 58.9%). The selective nature of this crisis is also evident within rays and sharks. Certain groups of sharks still present today (orectolobiformes, lamniformes) were more severely impacted, and groups of rays (rajiformes, rhinopristiformes) even came close to complete extinction, although they now number several hundred species.

Paleodiversity studies provide only a partial view of the consequences of a crisis on the structure and functioning of ecosystems. We therefore needed to assess the impact of this crisis on the different ecological groups represented among elasmobranchs. We therefore focused on the diets of the shark and ray species most affected by extinction by studying the morphology of their teeth. We were able to separate species that are known as "durophages" (feeding on hard prey, such as bivalve mollusks represented today by oysters, clams, mussels, and other scallops) from other species (non-durophages) and analyzed the extent of this crisis on these two ecological categories. Our results indicate that shark and ray species with teeth specialized for a durophagous diet were more severely affected (73.4% extinction) than others (59.8%). This is an interesting point because it has been shown that this extinction has had a major impact on the first links in marine food webs (plankton) and organisms directly dependent on them (e.g., bivalves). Our results therefore suggest a cascade of events that caused a huge loss of diversity among hard-feeding elasmobranchs. This represents a second type of selectivity, this time ecological, against species that feed on shelled prey.

Our analyses indicate that sharks—and particularly non-durophagous species—returned to pre-crisis diversity levels more quickly (still taking several million years) than rays, which had not fully recovered even 10 million years after the extinction. Furthermore, this crisis had a major effect on the composition of the elasmobranch fauna that survived the extinction, profoundly reshaping the diversity of this group. These changes are particularly marked in rays, where we see diversification in a group called Myliobatiformes (stingrays, eagle rays, etc.), which likely took advantage of the ecological niches left vacant by the extinction to diversify.

Finally, we tested the effect of species' geographic distribution on their probability of surviving this crisis. To do this, we compiled the geographic range of all species that became extinct or survived extinction. Our results show that species with a wide geographic distribution had a higher survival rate than others. More interestingly, species living at low latitudes were more severely affected, suggesting geographic selectivity.

The causes of this crisis are debated and certainly multiple (asteroid, of course, but also volcanism, climate cooling, falling sea levels). Although our study does not offer a direct answer to this debate, it does provide clues as to the possible mechanisms that played a role in this crisis, in particular our findings on the greater extinction at low latitudes.

Today, one-third of shark and ray species are threatened with extinction, and it is important to understand how the evolutionary history of this group has been impacted by previous extinctions and how this group has survived these extinctions. Our study proposes a kind of profile of extinction victims for the last mass extinction and also gives an idea of the time needed for post-extinction recovery. A time that is measured in millions of years.

Guillaume Guinot, Paleontologist, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.