Tardigrades can withstand (almost) anything, thanks to genes from extinct species

Tardigrades are small but tough: X-rays, extreme temperatures, enormous pressure—they demonstrate incredible resistance. A new study shows that as they evolved, they acquired genes from other species that gave them these "superpowers."

Simon Galas, University of Montpellier and Myriam Richaud, University of Montpellier

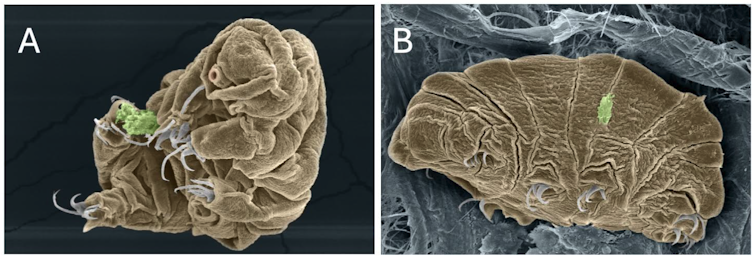

Imagine a tiny organism found everywhere on our planet around us, carrying with it a lost genetic memory. Tardigrades are invertebrates measuring between 0.2 and 1.2 millimeters in length that resemble miniature bears with four pairs of legs, muscles, neurons, and microbiota. They can be found everywhere on our planet, from the ocean floor to the summit of the Himalayas.

Tardigrades are also known as water bears because they always live in environments where water is present, such as oceans, glaciers, rivers, or house gutters, but also in mosses and lichens on trees or rocks. There are already nearly 1,500 known species, and they are the survival champions of our planet and the undisputed kings of a very select club called extremophiles, organisms capable of surviving in the most extreme environments.

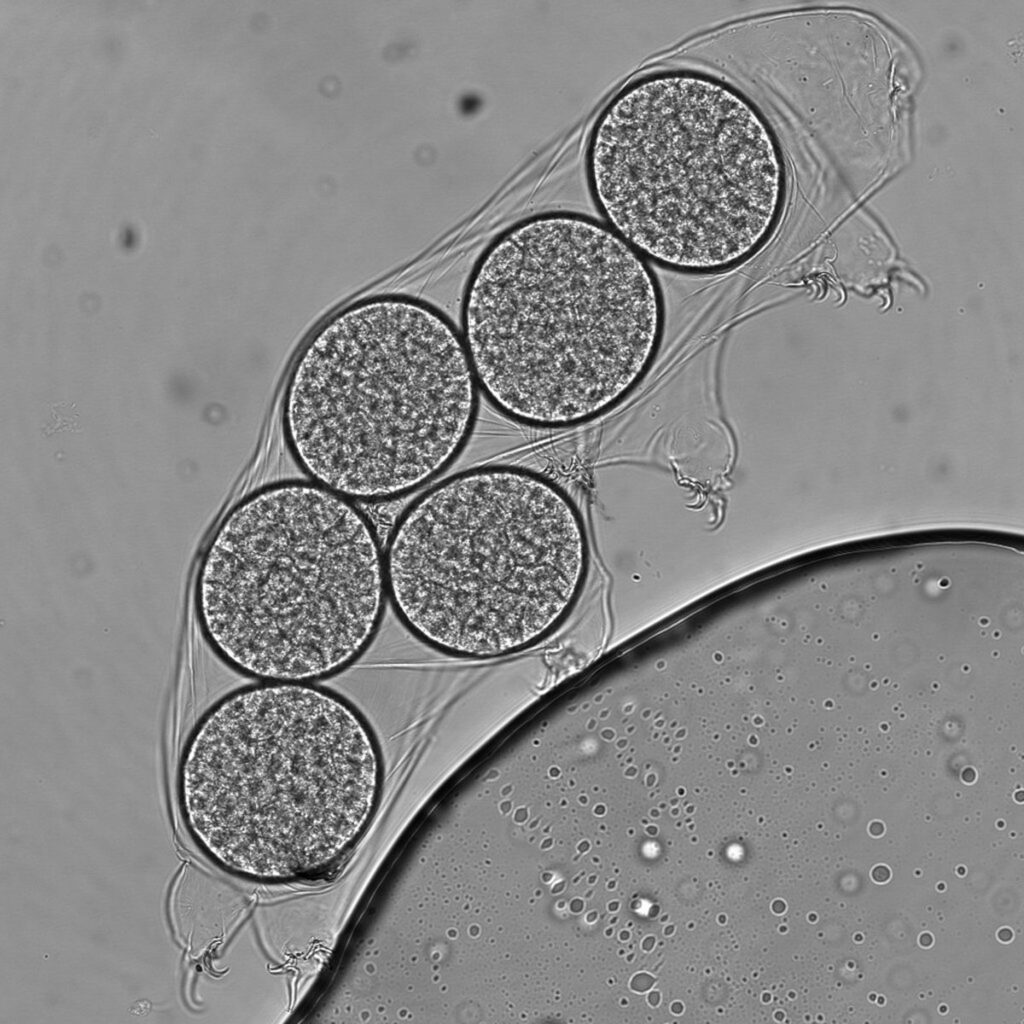

In fact, tardigrades are capable of withstanding the lowest temperature ever measured in the universe (-272°C) or a temperature close to that measured on the planet Mercury (+151°C). They can even survive temperatures close to absolute zero (-273.16°C), which does not exist in the universe but only in physics laboratories. In a recent physics experiment, one of three tardigrades of the species Ramazzotius variornatus, pictured below, was successfully revived after exposure to a temperature close to absolute zero.

Tardigrades can also survive a ten-day stay in the vacuum of space, directly exposed to cosmic rays, and have become a working model for astrobiology research. In terms of radiation, we know that they can survive doses of X-rays 1,000 times higher than the lethal dose for humans. Their resistance to enormous pressures has also been tested for several hours and, surprisingly, they survive being crushed by a weight equivalent to a 60,000-story building.

Cryptobiosis: life on hold

Tardigrades were first discovered in the18thcentury. After studying with the Jesuits in Reggio (Calabria, Italy), biologist and philosopher Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729-1799) published his first study on these tiny animals in 1776 in his book "Opuscules de physique animale et végétale" (Essays on Animal and Plant Physics). He gave them the name tardigrade and observed their ability to dehydrate completely and then "resurrect after death" in the presence of water, describing the phenomenon of cryptobiosis for the first time.

Cryptobiosis is a "state of suspended animation" during which no signs of life are detectable. In this state, tardigrades collected in Antarctica were successfully revived after thirty years. Other data has shown that tardigrades in cryptobiosis are in a "state of suspended life" but also "outside of time." In fact, the time spent in this state of cryptobiosis is not counted toward their normal lifespan (the average lifespan of a tardigrade species in controlled breeding is approximately 60 days). In short, whether it enters cryptobiosis or not, a tardigrade will not see its normal active life expectancy changed. Anglo-Saxons refer to this phenomenon as "Sleeping Beauty," indicating that an organism stops aging as long as it remains in this state.

Our CNRS laboratory in Montpellier was the first to successfully observe what happens inside a species of tardigrade (Hypsibius exemplaris) when it enters cryptobiosis. In this state, this species miniaturizes, losing 38% of its volume, and builds a kind of visible barrier around each of the cells that make up its body. This structure gradually disappears during the animal's reanimation.

Survival strategies that differ depending on the species

But the most surprising finding comes from a recent study conducted by our laboratory on a species related to the first (Ramazzottius varieornatus), also bred in our laboratories. When it enters cryptobiosis, this species miniaturizes by only 32%. Even more surprising, it is impossible to observe the presence of the specific cryptobiosis barrier that surrounded the cells of the previous species. These experiments indicate that different species of tardigrades are capable of withstanding stresses that are fatal to other living species, but that they do so in different ways and using tools that are not common to all of them.

Starting in 2016, this set of genetic tools enabling them to withstand extreme environments began to be identified during the first sequencing of their genomes. These tools are already attracting the interest of scientists for future revolutionary biomedical applications, such as the preservation of drugs and vaccines in a dehydrated form, or the protection of cells against lethal radiation, which would be useful for future space missions.

Geneticists believe that tardigrades acquired these genes to enable them to withstand dehydration, but they also suggest that these same genetic tools enable them to withstand all types of deadly environments. By studying their genetic makeup, scientists were surprised to find that nearly 40% of tardigrade genes are unknown in other species currently living on our planet.

But where do these genes called "unique tardigrade genes" come from?

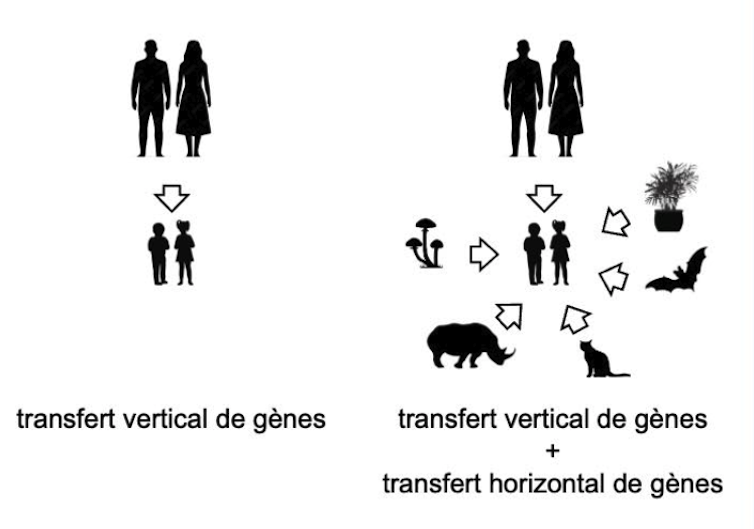

One explanation involves the mechanism of horizontal gene transfer (HGT). As outlined below, a living organism typically inherits genes from its parents vertically.

Acquire the genes of one's neighbors

In the case of horizontal gene transfer, the organism has an additional option, which is the ability to acquire genes from its neighbors and retain them if they prove beneficial to the survival of its species. This has already been observed in a species of aphid in which green individuals are eaten by ladybugs while red ones are parasitized by wasps. One aphid had the "bright idea" of acquiring a fungus gene through horizontal gene transfer and adopting a yellow color that protects it very effectively against both predators.

More recently, a new species of tardigrade identified in China was found to have acquired a gene from a species of bacteria that protects it against lethal doses of X-rays. In both of these examples, the organism responsible for this genetic gift has been identified because it is still alive, but in the case of the unique genes of tardigrades, this is not possible.

It would appear that tardigrades, which have inhabited our planet for around 600 million years, have had time to acquire numerous genes through horizontal transfer from species that are now extinct, building up a veritable library. This is all the more conceivable given that tardigrades have survived the five major extinctions of living species that our planet has experienced throughout its history. The most recent of these wiped out the dinosaurs. A small number of these unique tardigrade genes have already been identified and given bizarre names such as Dsup, TDR1, CAHS, SAHS, MAHS, TDPs, LEA, Doda1, and Trid1.

When placed in human cells or other laboratory organisms (fruit flies, bacteria, yeast, plants, etc.), these genes were able to dramatically increase their resistance to normally lethal treatments such as X-rays, ultraviolet rays, and powerful oxidants. Better still, proteins derived from some of these genes were able to protect drugs from dehydration, allowing them to be stored at room temperature and revealing enormous potential for the distribution of vaccines without the need for expensive freezers. The future use of these unique tardigrade genes in the biomedical field is already the subject of numerous patent applications heralding revolutionary new biomedical technologies that could soon emerge, ranging from protecting astronauts' skin from cosmic rays to the possibility of preserving drugs, tissues, or organs awaiting use.

A "DNA fragrance"

But where does this DNA that can be incorporated by tardigrades come from? The answer lies all around us. We are constantly surrounded by a "DNA scent" released by all the living organisms around us. This DNA is called environmental DNA(eDNA). A soil sample can be sequenced to determine which living species inhabit a given location, even without seeing them. This is a very effective technique for assessing the biodiversity of a terrestrial or marine environment. Recently, scientists have succeeded in identifying the DNA signature of Asian elephants and giraffes from samples taken from a spider web nearly 195 meters away in Perth Zoo in Australia.

Scientists have devised a possible scenario to explain how these pieces of eDNA can be found in tardigrade species as well as in certain worms and other invertebrates. These organisms all share the ability to survive dehydration for varying lengths of time.

When they are in cryptobiosis following dehydration, we observe the gradual appearance of breaks in their chromosomes.

Tardigrades will be able to repair this damage once they are rehydrated. Water is potentially capable of transporting DNA fragments to the cell nucleus where the chromosomes are located. Their presence among the fragmented chromosomes of tardigrades suggests that they may be integrated at the same time as the repair mechanisms are at work.

With their ability to capture new genes present in their environment, tardigrades have accumulated genes with exceptional properties from species that have long since disappeared from our planet. These unique tardigrade genes may hold the secrets to future biomedical revolutions by offering new possibilities for the protection and transport of fragile drugs and tissues, new protections for future missions already planned by space agencies, and even in dermocosmetics to combat the effects of aging.

Simon Galas, Professor of Genetics and Molecular Biology of Aging, IBMM CNRS UMR 5247 – Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Montpellier and Myriam Richaud, Doctor of Genetics and Molecular Biology of Aging, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.