Ticks and their bacteria: a dangerous combination

Ticks have a bad reputation, and this reputation is often justified. These animals are among the main vectors of pathogenic microorganisms for humans, but also for many other terrestrial vertebrates.

Olivier Duron, University of Montpellier

The list of diseases associated with tick bites and inoculated pathogens seems endless and, frankly, rather unpleasant: Lyme disease, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, spotted fevers, relapsing fevers, tick-borne encephalitis, and many more. (For more information: Ticks, fleas: Lyme disease, a real time bomb)

However, ticks do not only harbor pathogens; most of their microorganisms are in fact harmless. Our research, led by the CNRS in association with CIRAD, has recently established that certain bacteria are even necessary for the survival of ticks. Without these symbiotic bacteria, ticks suffer from premature developmental arrest, leading to slow decline. This symbiosis, which is so important for ticks, has its origins in their very specific diet.

From strict hematophagy to nutritional symbiosis

More than 900 species of ticks are known today! Some species are found in our hedgerows, some in tropical forests, and others even in Antarctica. However, they all have one thing in common: they are hematophagous, meaning they feed on blood, just like mosquitoes and fleas.

Florian Binetruy, Author provided

Unlike the latter, ticks feed exclusively on blood from the very beginning of their lives. They are strict hematophages. This highly specialized diet is not without consequences, because although blood is rich in protein, it is relatively poor in certain nutrients such as B vitamins. Ultimately, ticks should therefore suffer from nutritional deficiencies and waste away. However, this is not the case, and the reason why remained to be discovered.

While animals generally lack the ability to synthesize B vitamins, many bacteria are very good at doing so. But could they do this for ticks? Our initial studies on ticks quickly showed that they harbored pathogens, but more commonly symbiotic bacteria.

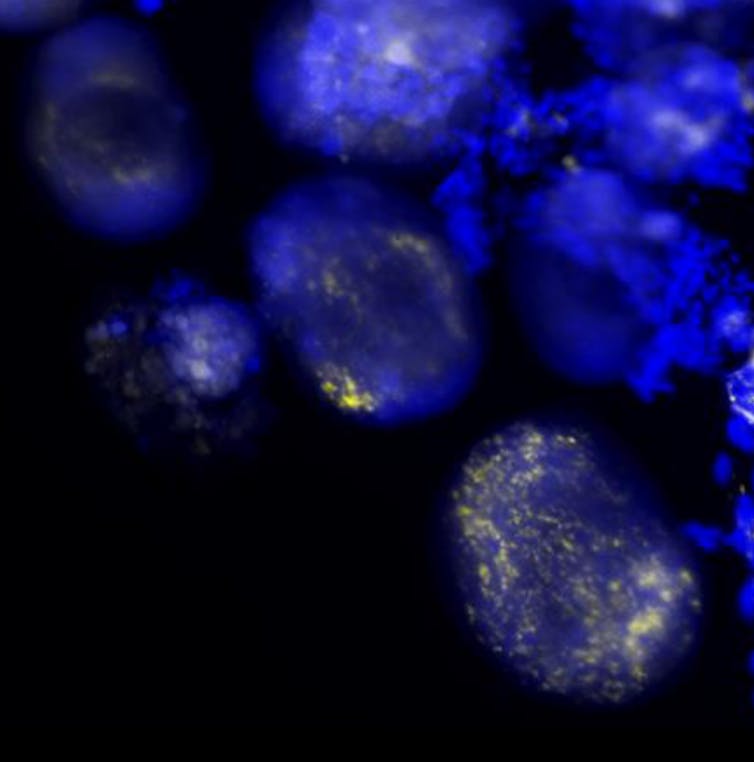

These bacteria were found in almost all of the ticks examined. The most curious fact is the location of these symbiotic bacteria in their bodies. Contrary to all expectations, these symbiotic bacteria are not part of the intestinal microbiota. Their lifestyle is much more specialized. They are obligate intracellular bacteria, unable to live in any environment other than a tick cell. The mode of transmission of these symbiotic bacteria is equally curious and allows ticks to be infected even before they hatch from their eggs.

Following a mode of transmission known as transovarian, mother ticks transmit these symbiotic bacteria via their own ovaries to their future offspring. This process results in perfect transmission, with all tick eggs carrying symbiotic bacteria. The symbiotic association is thus maintained in a stable manner from one generation of ticks to the next. Without interruption in this chain of transmission, the association can be maintained for a long time. The oldest known example is over 14 million years old, continues today, and involves ticks commonly found in dogs' ears. By comparison, 14 million years ago, the human lineage did not yet exist...

Supply of B vitamins by bacteria

It is these symbiotic bacteria that enable ticks to be strict hematophagous organisms. Sequencing of their genomes has revealed the presence of genes that enable the biosynthesis, i.e., the formation and production, of several types of B vitamins such as biotin, folic acid, and riboflavin. These biosynthesis pathways are intact and functional in all tick symbiotic bacteria examined to date.

Marie Buysse, Author provided

These B vitamins are vital for ticks, and anyone could find an original way to kill a tick: simply deprive it of these symbiotic bacteria. Adding a simple antibiotic such as rifampicin to the blood that ticks feed on will quickly eradicate the symbiotic bacteria and, in the medium term, cause a vitamin B deficiency. The ticks then stop developing, are unable to moult, and exhibit physical abnormalities. These symptoms are those of acute nutritional deficiency.

None of these symptoms appear if ticks deprived of symbiotic bacteria receive artificial supplementation of B vitamins. By becoming strictly hematophagous, ticks have thus become dependent on B vitamins and the bacteria capable of synthesizing them. Far from being insignificant, this process has enabled ticks to diversify and spread throughout most terrestrial ecosystems. Without this symbiotic association, none of the ticks we know today would exist. And the same would undoubtedly be true for the diseases associated with them.

The origin of symbiosis revealed by genomes

However, the story does not end there. Examining the genome of symbiotic bacteria also provides a better understanding of how this symbiosis came about and allows us to trace it back to its origins. Most symbiotic bacteria in ticks belong to bacterial genera that are well known to doctors and veterinarians: these genera, Francisella and Coxiella, contain species that are particularly virulent to humans and other vertebrates.

These pathogenic bacteria are responsible for infectious diseases that can sometimes be fatal, such as tularemia and Q fever. Tick symbiotic bacteria originate precisely from these bacterial genera, but during evolution, while some strains of Francisella and Coxiella evolved to form a symbiotic relationship with ticks, others evolved to become virulent to vertebrates, including humans.

Today, these two major types of lineage, symbiotic versus pathogenic, have diverged significantly, while retaining several common features. The first feature is their ability to colonize and multiply in the cells of their hosts—ticks in one case, humans and other vertebrates in the other.

The second point is the need for them to synthesize B vitamins, although the purpose of this production differs greatly. For symbiotic bacteria, this synthesis of B vitamins is key to their mutualistic interactions with ticks. For pathogenic bacteria, this synthesis is absolutely necessary for their multiplication and, ultimately, their virulence towards human cells or other vertebrates. The same mechanism—the synthesis of B vitamins—has therefore led to radically different evolutions between symbiotic and pathogenic lineages.

What does this discovery allow us to understand?

This symbiotic relationship illustrates the close interconnections that can develop within living organisms. The interdependence between a tick and its symbionts is such that they form a single biological entity, where one cannot live without the other.

This process is a powerful evolutionary driver behind ecological innovations: by enabling the emergence of the highly specialized diet of strict hematophagy, symbiosis allowed the ancestor of ticks to occupy new ecological niches.

![]() This ancestor then diversified into multiple species as we know them today. In terms of the research we conduct in our laboratories, this discovery also shows us that studying ticks solely through the prism of their pathogens is reductive. It invites us to explore new avenues of research to better understand how the diversity of the living world is generated and structured.

This ancestor then diversified into multiple species as we know them today. In terms of the research we conduct in our laboratories, this discovery also shows us that studying ticks solely through the prism of their pathogens is reductive. It invites us to explore new avenues of research to better understand how the diversity of the living world is generated and structured.

Olivier Duron, CNRS Research Fellow, University of Montpellier

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.