The impact of pellets and drops: same fight

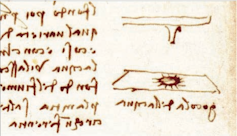

The impact of a drop on a surface has always fascinated mankind. As early as 1501, Leonardo da Vinci recorded delicate figures of splashes in his Leicester Codex, and inthe 19th century, Worthington published the first comprehensive study on the shapes adopted by drops of liquid falling vertically onto a horizontal plate.

Christian Ligoure, University of Montpellier

CC BY

The development of ultra-fast cameras capable of recording 10,000 images per second, has led to considerable progress in the spatio-temporal description of a wide variety of impact phenomena that are invisible to the naked eye due to their extremely short duration (typically one hundredth of a second). The number of scientific publications in this field has exploded in recent years, driven by the variety of natural and industrial situations in which this phenomenon occurs. Paradoxically, the study of the impact of gel beads or, more generally, small soft objects or drops of viscoelastic and deformable fluids has attracted much less research.

We recently decided to revisit the impact of different millimeter-sized objects on a solid surface and showed that this phenomenon obeys a very simple unified behavior regardless of the nature of the impacting object.

By covering the impact surface with a very thin layer of liquid nitrogen (very cold) that vaporizes on contact with the object at the moment of impact, forming a small cushion of nitrogen vapor, energy losses due to solid or viscous friction, which are highly dependent on the object/impact surface combination, can be eliminated. This is known as the inverse Leidenfrost effect. This makes it possible to film the expansion and then the retraction of the deformed object under ideal conditions of minimal dissipation, at different impact speeds.

When falling freely from a height of 1 m, the small, incompressible, millimetric spherical object acquires kinetic energy proportional to its mass and the square of its impact velocity, crashing at a typical speed of around 4 m/s. At the moment of impact, the stopped object deforms violently: it flattens and forms a pancake whose diameter increases to a maximum value that can reach six times the initial diameter. Then it retracts to reform the initial ball or drop, which bounces. The sequence lasts about one hundredth of a second. The impact is elastic and the ball's energy must be conserved: its kinetic energy decreases and is gradually transformed into elastic deformation energy, which is stored in the expanding pancake until it reaches its maximum size, at which point the conversion is complete. The process is then reversed during retraction.

Elastic energy

But what is the nature of this elastic deformation energy? For simple liquids, for which there are no intermolecular bonds, it is surface energy, which is proportional to the area of the object.

The coefficient of proportionality is called surface tension and has the dimension of energy per unit area: at the surface of a dense medium, the molecules that make up the material are not strictly in the same state as those inside, since they interact with fewer neighbors.

This new local state results in a small increase in the energy of each molecule on the surface. The surface of a medium is therefore associated with an energy per unit area, or surface tension, which originates from the cohesive force between identical molecules. This force is responsible, for example, for the spherical shape of a drop at rest (which corresponds to the minimum area for a given volume), or for allowing small insects such as water striders to walk on water.

What about solids?

For solids, there is also elastic energy of volume deformation; this comes from the deformation of the bonds in the molecular network that makes up the solid and is characterized by an elastic modulus of deformation, which has the dimension of energy per unit volume (or pressure).

By construction, the ratio between the surface tension of a material and its elastic modulus has the dimension of a length called the elastocapillary length, which is characteristic of a material (it is infinite for a simple liquid).

For objects much smaller than their elastic capillary length, surface energy controls the deformation of the object; conversely, for objects much larger than this capillary length, volumetric elastic energy prevails.

Pour des objets de taille comparable à la longueur élastocapillaire ; les deux modes de déformation élastique sont à prendre en compte. Pour la plupart des solides usuels (solides cristallins, métaux., verres) le module élastique est très élevé et varie tandis que la tension superficielle varie peu de sorte que la tension superficielle ne joue un rôle seulement significatif dans la déformation que pour des objets de taille colloïdale (<1 micromètre) ou même nanométrique.

For gels, which consist of a cross-linked network of polymer chains suspended in water, the volumetric elasticity is of a different nature (known as rubber elasticity), with elastic moduli that can be very low, between 1 and 10,000J/m3; this makes it possible to formulate ultra-soft solids. If the bonds in the network are transient, we are dealing with a viscoelastic fluid that will behave like a solid for times shorter than its relaxation time and like a liquid beyond that time. For these objects, the elastocapillary length can vary between 1 mm and 10 cm, exactly in the range where the impact of drops or balls can be observed, and both elastic energies play a role!

The impact dynamics of these objects—gel beads, viscoelastic droplets, and simple liquid droplets—are described in the absence of dissipation by very simple scaling laws based on impact velocity, which are identical regardless of the nature of the object.

It is as if the deforming tablecloth behaves like a simple spring that is being pulled, and whose stiffness constant is simply expressed in terms of physical quantities that characterize the mechanical properties of the object: its size, surface tension, elastic modulus of deformation, and density.

A new characteristic velocity of generalized elastic deformation associated with the impact of each object naturally appears in this description, combining the propagation velocity of transverse sound waves in the medium (the solid component) and the Rayleigh velocity associated with the vibration of a spherical liquid drop (the liquid component). The impact situations of a simple liquid drop or a "hard" elastic ball then appear simply as the limits of a unified behavior.![]()

Christian Ligoure, Professor, Soft Matter Physicist, University of Montpellier

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.