[LUM#8] The hidden life of our genes

While genetics is the study of genes, epigenetics focuses on how these genes are expressed. It is a promising field that opens up new horizons for medical research.

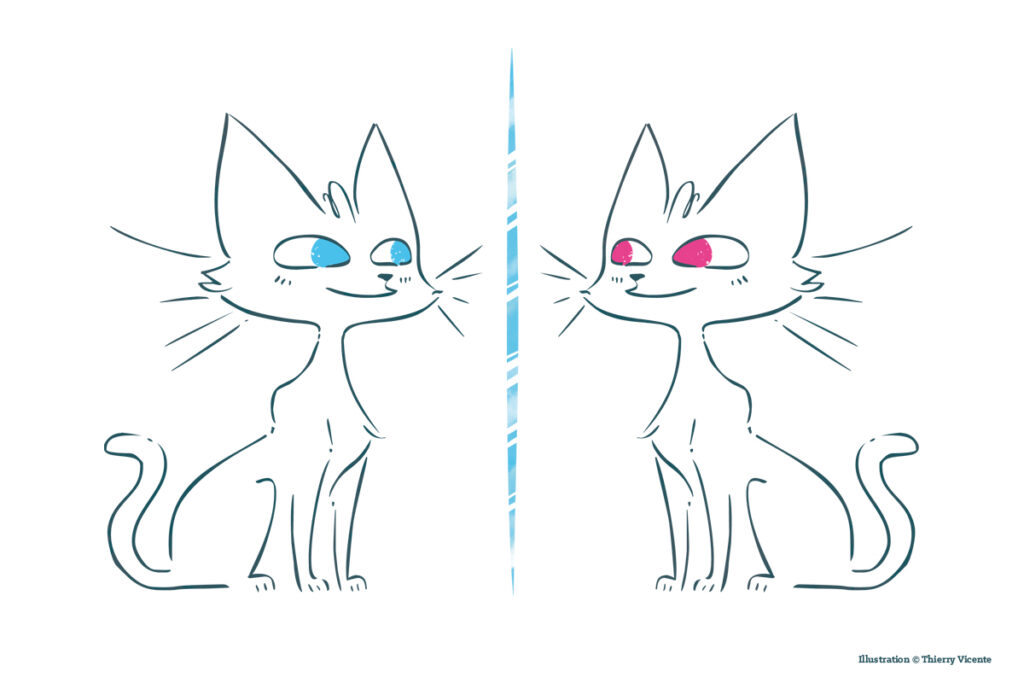

In 2001, a kitten unlike any other made headlines around the world. Its name: Carbon Copy. What made it so special? This furry ball was a clone. It had exactly the same genetic makeup as the cat it came from. However, one characteristic was not immediately obvious: although the two felines had exactly the same DNA, they did not have the same coat. How can two clones, carrying the same genes, be so different? "Heredity is not limited to our genes alone, because DNA does not carry all the information," replies Giacomo Cavalli. This is the key to this surprising difference in fur: epigenetics.

Epigenetics is the study of changes in gene activity that are not linked to modifications in the DNA sequence. "Gene function depends not only on the primary sequence but also on a number of modifications to the chromosome," explains the researcher from the Institute of Human Genetics (IGH). These modifications correspond to biochemical marks affixed by specialized enzymes to DNA or to proteins called histones, which are responsible for compacting DNA so that it can be stored in the cell nucleus. The same genome can therefore be expressed differently depending on epigenetic modifications (see box).

Identical but different

While these modifications play a major role in embryonic development, they also occur throughout life, particularly under the influence of the environment: what we eat, what we drink, and the products we are exposed to cause epigenetic modifications that affect our biology... and perhaps also that of our descendants. "Epigenetics is a mechanism of inheritance that adds to genetic inheritance," explains Frédéric Bantignies of the IGH.

The two researchers discovered a new mechanism of epigenetic inheritance in Drosophila. By modifying the structure of chromosomes at the level of the genes that produce eye pigments, they obtained flies with identical DNA but varying eye colors. They then observed the offspring of these Drosophila flies and noticed that this change in eye color was passed on to their offspring.

Are the epigenetic changes we carry also passed on to our children and grandchildren? This is what some observational studies of populations suggest, such as the "Dutch mothers" study, a group of pregnant women exposed to famine during World War II. Malnourished, these women gave birth to low-weight babies. Once the famine was over, these children grew up with a normal diet, yet when they had children of their own, they gave birth to low-weight babies. "The effects of undernourishment on these women were passed on to their grandchildren, even though they did not affect the DNA sequence, so these are epigenetic changes," explains Giacomo Cavalli.

Therapeutic hope

Are we, in this case, shaped by the behaviors of our grandparents and the epigenetic modifications induced by their environment? "In reality, it seems that very few of these epigenetic modifications are passed down through generations, and we don't yet know how," replies Frédéric Bantignies. "This is a whole area of heredity mechanisms that remains unknown," adds Giacomo Cavalli.

This also opens up new perspectives for a whole area of medical research."Epigenetic modifications play a role in the development of certain diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and cancer,"explain the researchers. Unlike phenomena that affect the genome, these epigenetic variations can be "erased" by chemical treatments, offering hope for new therapies."There are already epigenetic drugs being tested to treat certain cancers,"the researchers say. Epigenetic drugs may one day make it possible to treat diseases that we are currently powerless to cure.

At the heart of our cells

Each cell in our body contains our entire genetic makeup in its nucleus: 46 chromosomes containing approximately 25,000 genes. A gene is a segment of DNA that contains the information necessary for the synthesis of the molecules that make up the organism. But for this synthesis to take place, the gene must be readable. This is where epigenetic modifications come in: by affixing biochemical marks to the DNA, they can alter the readability of the gene, and thus alter its expression. This explains why the cells in our body—which all have the same genome—are not identical. A skin cell differs from a neuron, which in turn has different functions from a heart cell, even though they all share the same DNA.

Find UM podcasts now available on your favorite platform (Spotify, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, etc.).