Marine Le Pen: the campaign of paradoxes

Everything seemed new in Marine Le Pen's third presidential campaign. In ten years, she has seen her vote share in the first round increase from 6,421,426 in 2012 to 7,678,491 (then 10,638,475 in the second round) in 2017, and finally to 8,136,369 on April 10 this year.

Emmanuel Négrier, University of Montpellier and Julien Audemard

This increase is all the more significant given that it continued despite the presence of a strong challenger from the far right, Éric Zemmour (2,485,935 votes in the first round).

Have these changes boosted Marine Le Pen's candidacy beyond her usual populist stance? In any case, they face limitations and paradoxes that we propose to explain.

A programmatic refocusing

The trauma of the debate between the two rounds of voting in 2017, where the candidate's lack of preparation for the confrontation between programs was glaringly obvious, convinced the National Rally of one thing: a campaign whose goal is to appear not only worthy of representation but also capable of governing requires in-depth work on the program. If the strategy is to win over a growing share of a right-wing electorate in need of leadership, then the program must be adapted to the structure of this electorate, which is notoriously older and more conservative, and for which spectacular measures (such as Frexit, for example) are undesirable adventures.

While Gilles Ivaldi counts a greater number of "social" measures, Marine Le Pen's program is no "more left-wing" than in 2017—quite the contrary.

Overall, the program still leans to the right, with measures such as increased inheritance tax exemptions, the abandonment of retirement at age 60 for all, and, after some hesitation, the rejection of a return to the solidarity tax on wealth (ISF). Not to mention, of course, what remains symbolically the social and economic pillar of Le Pen's program: overt and systematic discrimination between French citizens and foreigners in terms of social, health, and educational benefits.

A significant development in communication

However, there has been a clear shift in communication strategy, largely due to a change in Marine Le Pen's inner circle, with most of the 2017 campaign having been led by Florian Philippot. In 2022, she has surrounded herself with advisors mainly from the world of expertise, including the think tank Les Horaces, which somewhat mimics Les Gracques, a social-liberal think tank founded during the 2007 presidential campaign and which then fueled Emmanuel Macron's campaign in 2017. Well described by journalist Géraldine Woessner, Les Horaces, formed as a think tank in 2015, remained on the sidelines of the 2017 campaign.

While their numbers and importance within the French elite should not be exaggerated, valuable reinforcements have arrived in the form of members of ministerial cabinets, graduates of the École Nationale d'Administration (ENA), and representatives from the medical, social, and economic sectors, such as Jean-Philippe Tanguy (ESSEC, Sciences Po Paris), Nicolas Dupont-Aignan's former colleague, who at the age of 35 became deputy director of Marine Le Pen's campaign. The technicization of Marine Le Pen's entourage has therefore been carried out at the risk of appearing more "classically" right-wing than disruptive.

To accompany this refocusing, the style of the campaign was also significantly modified. The removal of harsh and potentially anxiety-inducing measures was accompanied by efforts to soften her image (the aunt saddened by her niece's betrayal, the staging of her relationship with cats, the care taken in welcoming people and the polite dialogue during her visits to various campaign locations). The reduced emphasis on rallies in favor of "micro-collective" visits also reinforced the idea of a low-key campaign, potentially aimed at softening her image.

But the major factor in refocusing Marine Le Pen's campaign came from outside and against her will. This was the key role played by Éric Zemmour, which was all the more useful in the first round as it validated the RN candidate's efforts to appear more "democratically" acceptable, in contrast to the polemicist's excesses.

The three roles of Éric Zemmour

Éric Zemmour fulfilled three roles in Le Pen's campaign. The first was to amplify the presence of far-right themes, such as identity and migration issues, which are generally attributed to him. Voiced loudly (by Zemmour) and transformed into a public action program (by Le Pen), these themes opened the Overton window of opinions worthy of debate in the public sphere in just a few months.

According to Joseph P. Overton (1960-2003), widening the window of opinion is a process that involves shifting ideas initially considered "unthinkable" to "radical," then "reasonable," then "popular," and finally leading to the adoption of public policies. Among these ideas in 2022 is, of course, the theory of the "Great Replacement," which has been played up by certain representatives of the Republican right, led by Valérie Pécresse.

Éric Zemmour's second role was to act as a tribune with an unapologetic radicalism, which in turn served as a "lightning rod" for the RN candidate. The best example here is the reference to the dream of a French Putin who, through his excesses, has protected Marine Le Pen from overly insistent references to her equally clear links with the Russian president and his entourage, particularly in the banking sector. During the debate on April 20, Emmanuel Macron's mention of these links did not fail to destabilize her.

Zemmour's third function is electoral. While the far right has, over the years, performed quite well in the first round of a majority election, it suffers in the second round from a lack of reserves and rallies. This time around, Zemmour's capital (with penetration into affluent segments that are reluctant to vote for Le Pen) appears to be available for a more open second round, if the two can be added together.

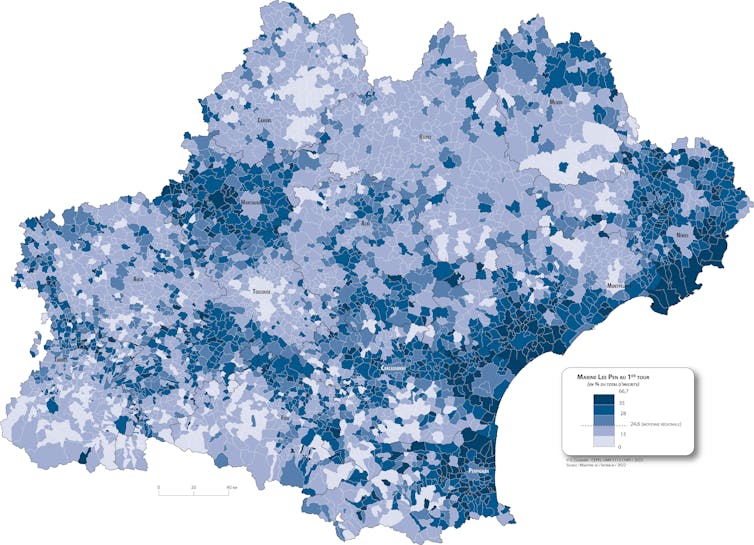

Stéphane Coursière/CEPEL, Provided by the author

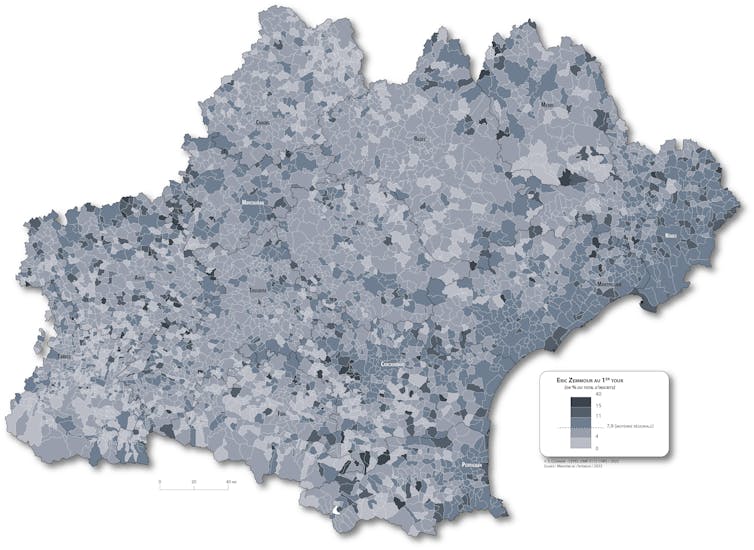

Stéphane Coursière/CEPEL, Provided by the author

The map of the first round shows how much the two electorates differ on an interregional scale. However, focusing solely on Occitanie, we can also see that Zemmour's electorate is strong in the very areas where Le Pen's vote is high: Aude, Gard, Pyrénées Orientales, and Hérault. This observation can be extended to the entire coastline. Marine Le Pen achieved 26.6% against Éric Zemmour's 14% in the Alpes-Maritimes, while the figures were 26.2% and 10.8% in the Bouches-du-Rhône, and 30.6% and 13.3% in the Var. But this map of possible transfers perhaps points to one of the paradoxes of Marine Le Pen's 2022 campaign, which must now be highlighted.

Two electoral boundaries

A first limitation of Marine Le Pen's campaign strategy is illustrated by the spatial distribution of votes in her favor: a comparison between the maps from 2017 and 2022 shows that the RN electorate has remained largely stable. While there has been some expansion of electoral support for Marine Le Pen, this is by no means widespread enough to suggest that voting for the far right has become commonplace. The map of the RN vote on Sunday, April 10, reveals gaps precisely where the party's efforts to shed its negative image could have had an effect. This is particularly true in urban centers, where the RN candidate's deficit is all the more significant given that voter turnout was relatively consistent across the country. In municipalities with more than 100,000 inhabitants, Marine Le Pen obtained an average of only 12.3% of the votes cast, compared to 29.5% for Emmanuel Macron and 31.3% for Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

This is also the case in the western part of the country, which has traditionally been more resistant to voting for the RN—the dividing line between Le Havre and Perpignan persists, despite the RN's gains across much of mainland France, both today and in the 1980s.

Added to this first limitation is a sociological one. The moderation of the party's discourse has not translated into an increase in RN votes among the upper classes, and the party's support remains largely popular. This tribunician paradox is all the more damaging to Marine Le Pen in her quest for power, as the vote in her favor faces the obstacle of the Mélenchon vote, which also performs very well among segments of the working class (lower civil servants, voters of immigrant origin, who are mostly hostile to the far right ).

These two limitations mean that the RN's electorate is undoubtedly still too specific to hope for victory in the second round of the presidential election, despite the candidate's intensified campaign, particularly in the west.

A political limit

Finally, Marine Le Pen's campaign strategy faces a third limitation, this time of a political nature. This limitation, which was clearly visible during the period between the two rounds of voting, can be broken down into three elements.

The first highlights the limitations of expertise. The debate on April 20, 2022, demonstrated this. Often embarrassed and defensive on the most technical points of her program, she failed to destabilize the incumbent candidate on his record.

By treating Marine Le Pen (almost) like an ordinary rival, he validated his change in strategy—his attempt to soften her image—in order to better dominate her in the realm of governance. At the same time, this period between the two rounds highlighted the difficulties faced by the candidate and her entourage in dealing with recurring criticism of the RN's traditional ideological base and its conservative and anti-immigration positions.

A second factor adds to this difficulty: despite her rising poll numbers, Marine Le Pen still suffers from a lack of support, including from the right and, at times, even within her own camp. This deficit can largely be explained by a third factor, which is the persistence of the Le Pen brand, still considered infamous by many.

On Sunday, April 24, a majority of voters will have to choose between two negative emotions: fear of a Le Pen presidency, the incumbent president's trump card, and resentment toward Emmanuel Macron, which the RN candidate intends to capitalize on. For Marine Le Pen, this dangerous choice raises two major questions: her ability to maintain the popular vote beyond the presidential election, which she seems to have secured, while consolidating her territorial expansion and the normalization on which she relies.

From this perspective, bringing together Le Pen and Zemmour's electorates will undoubtedly be key to achieving lasting leadership. In the longer term, the challenge for the RN will be to overcome the divide between the two popular blocs represented by Le Pen and Mélenchon voters. Between respectability on the right and popular legitimacy, all the contradictions of a campaign are laid bare.![]()

Emmanuel Négrier, CNRS Research Director in Political Science at CEPEL, University of Montpellier, University of Montpellier and Julien Audemard, Associate Research Scientist

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.