Oceans and climate: what options for tomorrow? A look at research in France

In a few days, the third United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC 3) will be held in Nice, France (Alpes-Maritimes). It will bring together leaders, decision-makers, scientists, and stakeholders from around the world with the aim of "accelerating action and mobilizing all actors to conserve and sustainably use the ocean," with the possibility of a "Nice Agreement" consisting of a political declaration negotiated at the UN and voluntary declarations—at least, that is the goal of the organizers, France and Costa Rica.

Scientific information is essential to support these decisions—what is the status of research worldwide and in France on exploiting the solutions that the ocean can offer in the face of the climate crisis?

Devi Veytia, École Normale Supérieure (ENS) – PSL; Adrien Comte, Institute for Research and Development (IRD); Frédérique Viard, University of Montpellier; Jean-Pierre Gattuso, Sorbonne University; Laurent Bopp, École normale supérieure (ENS) – PSL; Marie Bonnin, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Yunne Shin, Institute for Research and Development (IRD)

France plays a key role in advancing the goal of conserving and sustainably using the ocean, since, with the world's second-largest exclusive economic zone, it wields considerable influence over the use of ocean resources.

However, fulfilling such a necessary and ambitious mandate to accelerate and mobilize action will not be easy. The UNOC 3 discussions will take place in a context where the ocean is facing challenges unprecedented in human history, particularly due to the increasingly significant impacts of climate change.

These effects are becoming increasingly apparent in all regions of the world, from the surface to the deepest waters of the Southern Ocean around the Antarctic continent to densely populated coastal areas where climate risks are accumulating, affecting fisheries in particular.

Ocean-based options for mitigating climate change (e.g., using marine renewable energy that limits greenhouse gas emissions) and adapting to its impacts (e.g., building sea walls) are essential.

To optimize their deployment, a comprehensive and objective synthesis of scientific data is essential. Indeed, an incomplete assessment of the available evidence could lead to biased conclusions, highlighting certain options as particularly suitable while neglecting their side effects or critical gaps in knowledge.

Amid this maelstrom of challenges, what is France's contribution to research and the deployment of ocean-based options?

Based on a study of 45,000 articles published between 1934 and 2023, we show that French researchers publish a significant proportion of global scientific research on adaptation options, but that there are still many levers for action.

For example, French scientific expertise could be developed to support research on adaptation in small island developing states, which are particularly vulnerable to climate change. In addition, research on mitigation options, for example in the field of marine renewable energy, should be expanded.

What are ocean-based options?

The ocean covers 70% of the Earth's surface and has absorbed 30% of human carbon dioxide emissions. Yet, until recently, it was neglected in the fight against climate change.

Today, many ocean-based options are emerging in dialogues between scientists, policymakers, and citizens. These "ocean-based options" involve actions that:

- mitigate climate change and its effects by using ocean and coastal ecosystems to reduce atmospheric greenhouse gas emissions; examples include interventions that use the ocean for renewable energy production;

- support the adaptation of coastal communities and ecosystems to the ever-increasing impacts of climate change; fisheries management and ecosystem restoration, as well as the construction of infrastructure to protect coastlines from flooding, are among these options.

Analyzing research using AI

One of the key roles of science is to provide an impartial synthesis of scientific data to inform decisions. However, the explosion in the number of scientific publications makes it increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to carry out these assessments comprehensively.

This is where artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models come in, which are already enjoying considerable success, from chatbots to Internet search algorithms.

In ongoing research currently under evaluation, we have extended these new applications of AI to the science-policy interface, using a large language model to analyze France's contribution to the landscape of research on ocean-based options. Using this model, we have classified approximately 45,000 scientific articles dedicated to ocean-based options.

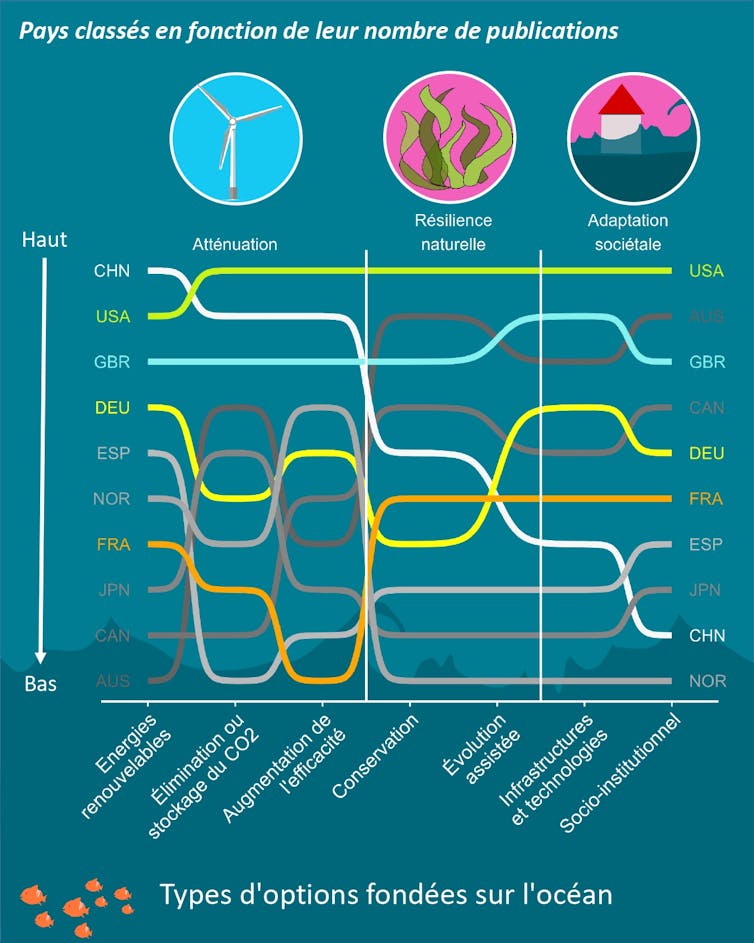

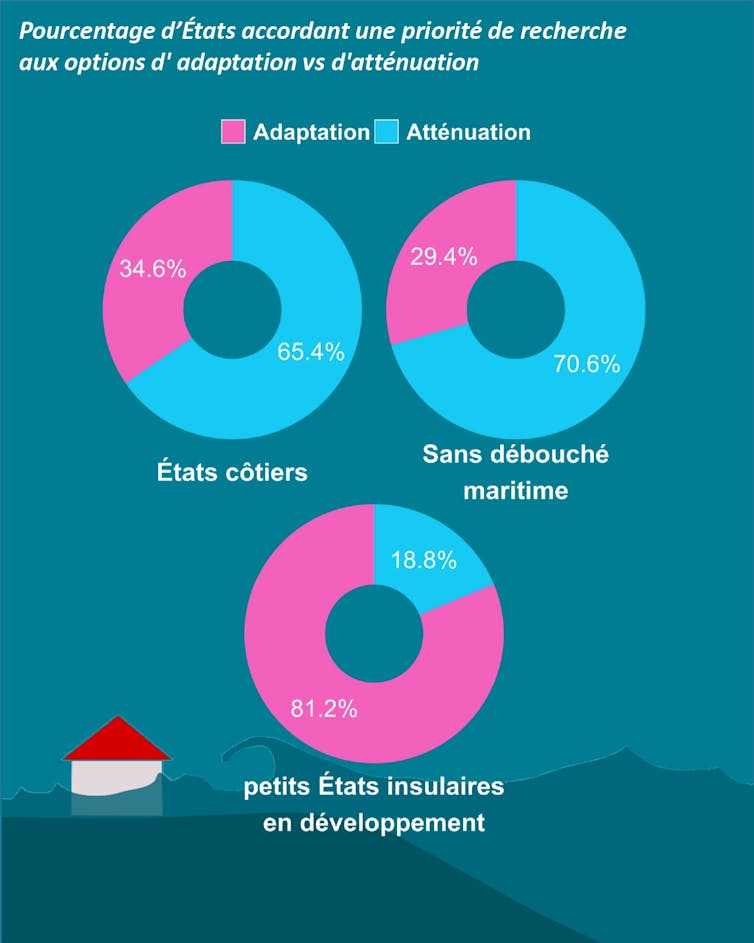

Globally, we see that research is unevenly distributed, with 80% of articles focusing on mitigation options. Researchers affiliated with France play an important role here, as they are among the leading contributors to research on adaptation options.

This priority for adaptation research is also evident in the work of researchers affiliated with institutions in small island developing states, which are at high risk from coastal hazards exacerbated by climate change, including extreme weather events and sea level rise.

Research on social networks and in the media

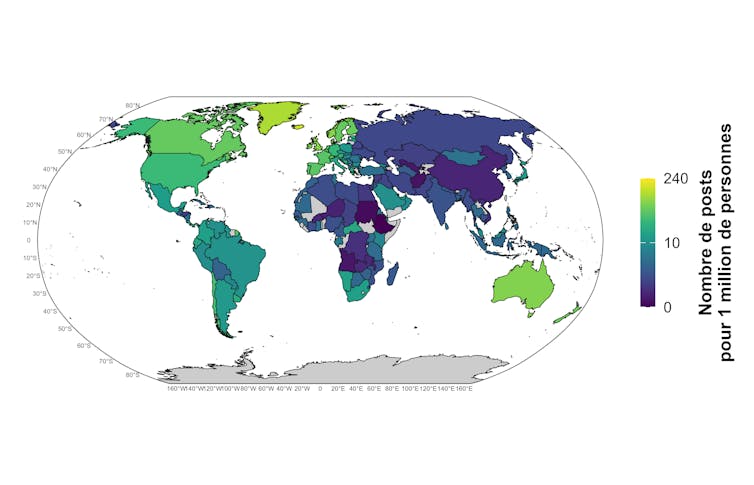

The impact of French research extends far beyond its borders, generating interest via social media and traditional media across Europe, North America, and Australia.

As access to information and dissemination platforms increases the reach and influence of public opinion in policy-making, it becomes crucial not only to communicate, but also to involve other actors in order to translate science into regulatory provisions and, ultimately, into concrete actions.

What obstacles stand in the way of turning ideas into action?

This evolution, from idea to action, is a classic progression in the life cycle of an intervention. First, a problem or potential impact is identified, which motivates scientific research to study its causes and develop solutions to address it. Once this stage is complete, the intervention can be incorporated into legislation, thereby encouraging stakeholders to take action. But is this process applicable to ocean-based options, or are there additional obstacles to consider?

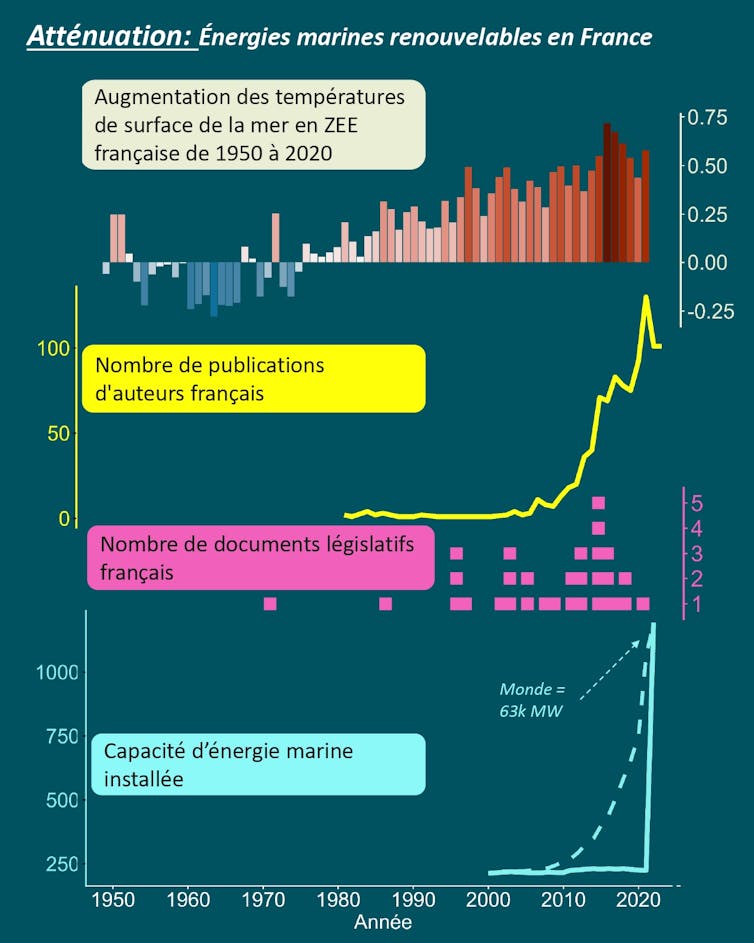

We studied this situation in France for two technological options that are ready to be deployed and have already been implemented: marine renewable energies, proposed to mitigate climate change, and infrastructure built and societal adaptation technologies to cope with rising sea levels.

With regard to marine renewable energy—a measure considered effective in mitigating climate change and whose risks are well documented and moderate—deployment in France appears slow compared to the rest of the world (dotted line in the figure below).

On the other hand, the levers for action in favor of societal adaptation infrastructure seem to be more mobilized in the face of growing pressure from coastal climate risks.

Thus, we see that as sea levels rise and, consequently, the need for coastal protection increases, research, legislation, and action (represented by the number of French municipalities exposed to coastal risks that have a natural risk prevention plan (PPRN)) are also on the rise, particularly since 2010.

In summary, when it comes to marine renewable energy, France lags behind the rest of the world in terms of turning ideas into action. This could be explained by the priority given to other mitigation measures (e.g., nuclear energy). However, we should not limit ourselves to one or a few options in order to increase our overall mitigation potential. France has the opportunity to invest more in research and mitigation actions.

France has a very good track record in researching and implementing climate change adaptation options. Furthermore, we have identified a global need for research into these types of options in developing countries exposed to coastal risks—which could open up new opportunities for French research institutions in terms of supporting research and strengthening their capacities in these areas.

As we approach UNOC 3—a critical moment for decision-making—one thing is clear: there is no single solution, but choices must be made. It is therefore essential to find ways to quickly evaluate and synthesize scientific evidence to inform our actions today, as well as to propose new avenues of research ahead of tomorrow's innovative actions.

Devi Veytia, Ph.D., École normale supérieure (ENS) – PSL; Adrien Comte, Research Fellow, Institute for Research and Development (IRD); Frédérique Viard, Director of Research in Marine Biology, University of Montpellier; Jean-Pierre Gattuso, Research Professor, CNRS, Iddri, Sorbonne University; Laurent Bopp, Research Professor, CNRS, École normale supérieure (ENS) – PSL; Marie Bonnin, Research Director in marine environmental law, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Yunne Shin, Researcher in marine ecology, Research Institute for Development (IRD)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.