Oceans: fish, an invisible carbon sink threatened by fishing and climate change

The oceans play a major role in carbon storage, particularly through the biomass they contain. The life cycle of fish thus contributes to permanently trappingCO2 in the deep sea, but industrial fishing has weakened this essential mechanism, which is also threatened by climate change. Restoring marine populations in the high seas could strengthen this natural carbon sink while limiting conflicts with food security.

Gaël Mariani, World Maritime University; Anaëlle Durfort, University of Montpellier; David Mouillot, University of Montpellier and Jérôme Guiet, University of California, Los Angeles

When we talk about natural carbon sinks, those natural systems that trap more carbon than they emit, we tend to think of forests and soils rather than oceans. However, oceans are the second largest natural carbon sink.

The impact of human activities (and fishing in particular) on ocean carbon storage had previously been little studied, even though marine macrofauna (especially fish) accounts for about one-third of the organic carbon stored by the oceans. Our research, recently published in the journals Nature Communications and One Earth, aimed to remedy this situation.

Our findings show that fishing has already reduced carbon sequestration by fish by nearly half since 1950. By the end of the century, this decline is expected to reach 56% due to the combined effects of fishing and climate change. This calls for more sustainable ocean management that takes into account the impact of fishing on carbon sequestration.

Why should we be interested in carbon sequestration in the oceans?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states explicitly in its reportsthat in order to achieve climate goals, we must first drastically and immediately reduce our greenhouse gas emissions (each year, human activities emit around 40 billion tons of CO₂ equivalent), then develop nature-based climate solutions.

These include all measures to restore, protect, and better manage ecosystems that trap carbon, such as forests. These measures could capture 10 billion tons of CO₂ equivalent per year and must be implemented in addition to emissions reduction policies.

However, the carbon stored by these ecosystems is increasingly threatened by climate change. For example, forest fires in Canada emitted 2.5 billion tons of CO₂ equivalent in 2023: the forest is no longer a carbon sink, but has become a source of emissions.

Faced with this situation, the scientific community is now turning to the oceans in search of new solutions that would enable more carbon to be sequestered there.

But for this to be possible, we must first understand how life in the oceans interacts with the carbon cycle and the influence of climate change on the one hand, and fishing on the other.

What role do fish play in this process?

The vast majority of the 38 trillion tons of carbon stored by the ocean is stored through physical phenomena. But ocean biomass also contributes to this, accounting for approximately 1.3 trillion tons of organic carbon. Fish represent approximately 30% of this carbon stock.

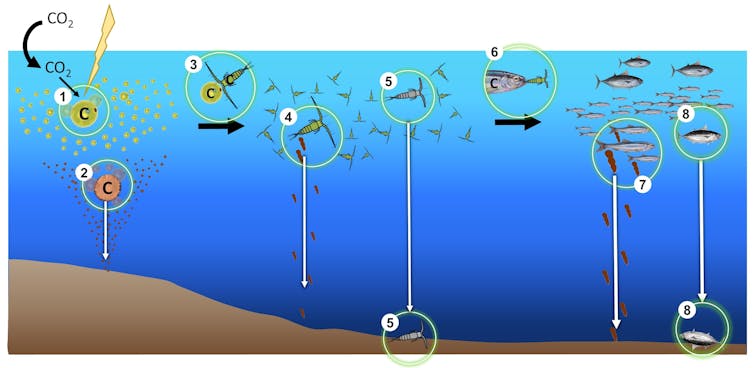

This is made possible by their contribution to what is known as the biological carbon pump, i.e., the series of biological processes that transport carbon from surface waters to the seabed. It is a major component of the carbon cycle.

This biological pump begins with phytoplankton, which is capable of transformingCO2 into carbon-based organic matter. When it dies, some of this carbon sinks to the depths of the ocean where it will be sequestered permanently, while the rest will be ingested by predators. Once again, it is when this carbon sinks to the depths (fecal pellets, carcasses of dead predators, etc.) that it will be permanently sequestered.

Fish play a key role in this process: their carcasses and fecal pellets, which are denser, sink much faster than those of plankton. The faster carbon sinks to the depths—and away from the atmosphere—the longer it will take to return to the atmosphere, meaning that carbon will be stored more sustainably.

Our study, which focused specifically on commercially important fish species (i.e., those targeted by fishing), estimates that these species were capable of sequestering 0.23 billion tons of carbon per year in 1950 (equivalent to 0.85 tons ofCO2 per year).

A vicious cycle caused by climate change

But since 1950, things have changed. First, due to climate change: because of the scarcity of food resources (less phytoplankton) and changes in environmental conditions (temperature, oxygen, etc.), the more severe the climate change, the more the biomass of commercially important species—and by extension, their ability to sequester carbon—will decline.

- In a scenario where the average temperature increase is limited to 1.5°C (the Paris Agreement scenario), biomass would decline by around 9% by the end of the century, representing a reduction in carbon sequestration of around 4%.

- In a business-as-usual scenario where temperatures rise by 4.3°C, this decline would reach approximately 24% for biomass and nearly 14% for carbon sequestration.

We are therefore dealing with what is known as a positive feedback loop—in other words, a vicious circle: the more significant climate change is, the less carbon fish will sequester, which will exacerbate climate change itself. It's a vicious circle.

Carbon sequestration already halved by fishing

The impact of climate change in a scenario of 1.5°C warming (which we are on track to exceed) therefore remains low, but the effects of fishing are already visible.

Today, commercial fish species already trap only 0.12 billion tons ofCO2 per year (compared to 0.23 billion tons of carbon per year in 1950), a decrease of nearly half.

This is especially true given that the effects of fishing vary depending on the sequestration pathway considered. Since 1950, fishing has reduced carbon sequestration via fecal pellets by approximately 47%. For the pathway involving carcasses, this reduction is approximately 63%.

This is linked to the fact that fishing targets the largest organisms, i.e., those that have the fewest predators—and are therefore the most likely to die of old age and have their carcasses sink into the abyss.

This decline also means less food reaching the deep sea, as carcasses are a particularly nutritious resource for the organisms that live there.

However, we know very little about these deep-sea ecosystems, with millions of species still to be discovered. So far, we have only observed 0.001% of the total surface area of these ecosystems. We may therefore be starving a multitude of deep-sea organisms that we know very little about.

To protect the climate, restore fish populations?

Our study shows that if fish populations were restored to their historic 1950 levels, this would enable an additional 0.4 billion tons ofCO2 to be sequestered each year, a potential comparable to that of mangroves. With one advantage: this carbon would be sequestered for around 600 years, which is longer than in mangroves, where only 9% of the carbon trapped remains after 100 years.

However, despite this significant potential, climate solutions based on the restoration of marine macrofauna, if implemented alone, would have only a minor impact on the climate, given the 40 billion tons of CO₂ emitted each year.

This is especially true given that this field of research is still in its infancy and several uncertainties remain. For example, our studies do not take into account trophic relationships (i.e., those related to the food chain) between predators and their prey, which also contribute to carbon sequestration. However, if the biomass of predators increases, the biomass of prey will automatically decrease. Thus, if carbon sequestration by predators increases, that of prey decreases, which can neutralize the impact of measures aimed at restoring fish populations to sequester carbon.

Therefore, our results should not be seen as sufficient evidence to consider such measures as a viable solution. Nevertheless, they illustrate the importance of studying the impact of fishing on carbon sequestration and the need to protect the ocean in order to limit the risks of depleting this carbon sink, while taking into account the services provided by the ocean to our societies (food security, jobs, etc.).

Conflicts between fishing and carbon sequestration, especially on the high seas

Marine organisms play a direct role in carbon sequestration, while also benefiting the fishing industry. This industry is a major sourceof employment and economic income for coastal communities, contributing directly to maintaining and achieving food security in certain regions.

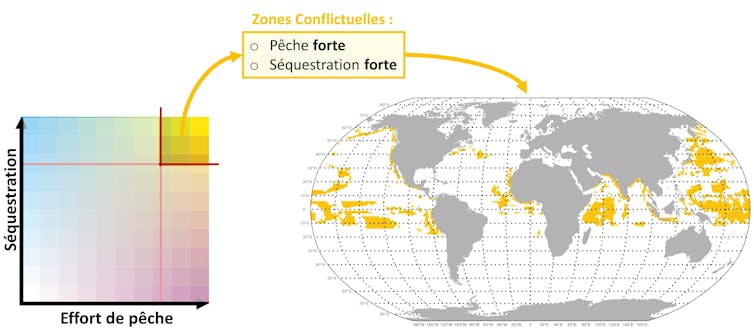

Conflicts between carbon sequestration and the socioeconomic benefits of fishing may therefore theoretically arise. If fishing increases, fish populations and their capacity to sequester carbon will decline, and vice versa.

However, we have shown that only 11% of the ocean surface is potentially exposed to such conflicts. These are areas where both fishing effort and carbon sequestration are high.

Furthermore, the majority (around 60%) of these potentially conflict-prone areas are located on the high seas, where catches make a negligible contribution to global food security. Furthermore, deep-sea fishing is known for its low profitability and massive government subsidies (amounting to $1.5 billion, or more than €1.2 billion, in 2018).

These government subsidies are strongly criticized because they threaten the sustainability of small-scale coastal fisheries, promote fuel consumption, and increase inequalities between low- and high-income countries.

Our findings therefore provide further justification for protecting the high seas. In addition to avoiding multiple negative socioeconomic effects, this would also protect biodiversity and, at the same time, preserve the oceans' capacity to sequester organic carbon.

Gaël Mariani, Doctor of Marine Ecology, World Maritime University; Anaëlle Durfort, PhD student in marine ecology, University of Montpellier; David Mouillot, Professor of Ecology, MARBEC Laboratory, University of Montpellier and Jérôme Guiet, Researcher in marine ecosystem modeling, University of California, Los Angeles

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.