Omicron, Delta, Alpha… Understanding the dance of variants

Discovered on November 25 and declared "of concern" by the WHO the following day, the Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) is being closely monitored by numerous teams. Researchers from the "Infectious Diseases and Vectors: Ecology, Genetics, Evolution, and Control" unit " (University of Montpellier, CNRS, IRD), Mircea Sofonea, associate professor, and Samuel Alizon, director of research, specialists in the epidemiology and evolution of infectious diseases, review the dynamics of variants. The prevalence of Delta, the particularities of Omicron... Explanations in 10 key points by the two specialists.

Samuel Alizon, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Mircea T. Sofonea, University of Montpellier

The Conversation: Why did Delta dominate all other SARS-CoV-2 variants for months?

Samuel Alizon: The Delta variant is quite "monstrous." This can be seen, for example, in estimates of the basic reproduction number, R₀ (the average number of infections caused by one infected person in a given population). Our team estimated it to be around 3 in a March 2020 report for ancestral lineages in France. For the Alpha variant, the R₀ was between 4 and 5, which explains its rapid spread in early 2021. For Delta, estimates are between 6 and 8.

On pourrait presque parler d’un avantage « qualitatif » sur les autres variants, comme le signalent les études de terrain : si contrôler la propagation des lignées ancestrales revenait à stopper la propagation d’une grippe pandémique (R₀ < 3), avec Delta cela s’apparente plus à contrôler un virus comme la rubéole (R₀ > 5). Ce choc est particulièrement violent pour les populations peu vaccinées ou immunisées, comme on l’a vu cet été aux Antilles ou plus récemment en Europe de l’Est.

Mircea T. Sofonea: Among human respiratory viruses, only mumps, chickenpox, and measles are more contagious, with R₀ values often estimated at over 10. And the faster a virus spreads, the longer it will take for another variant that is only slightly more contagious to emerge.

This is a result of evolutionary biology illustrated by Fisher's geometric model from the 1930s. Schematically, it amounts to considering each mutation as a random movement from one point to another on a landscape whose relief represents the virus's ability to spread among the human population. Through natural selection, only movements corresponding to an upward climb are retained. Fisher's model suggests that this ascent occurs more and more slowly, because the probability of a random movement landing on a higher point decreases as it approaches the top of the landscape, the adaptive optimum.

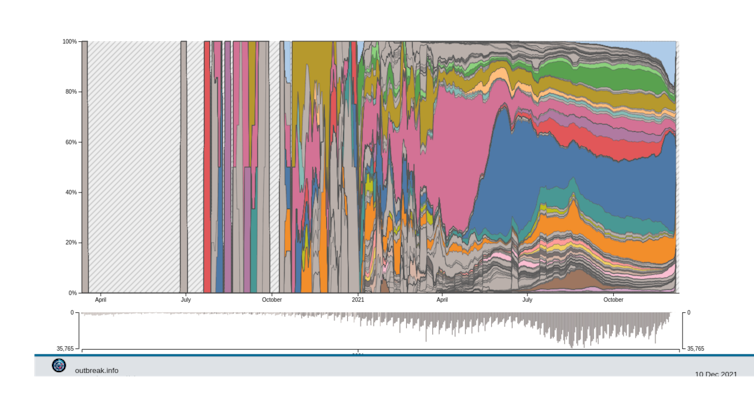

In fact, since July 2021, the number of variants has not exploded, and instead we have seen the Delta variant diversify into around a hundred sub-lineages —some of which are being monitored more closely due to the mutations of interest they carry.

Delta Variant Report. Alaa Abdel Latif, Julia L. Mullen, Manar Alkuzweny, Ginger Tsueng, Marco Cano, Emily Haag, Jerry Zhou, Mark Zeller, Emory Hufbauer, Nate Matteson, Chunlei Wu, Kristian G. Andersen, Andrew I. Su, Karthik Gangavarapu, Laura D. Hughes

T.C.: Can Delta maintain this advantage "indefinitely"?

S.A.: The more people become immune, whether through vaccination or, unfortunately, through infection itself, the more Delta's advantage diminishes. Indeed, we now know that other variants are better at evading immunity than Delta. The most common hypothesis is therefore that Delta will ultimately be replaced by strains capable of infecting immune hosts. For the moment, the Beta variant is the one for which laboratory tests detect the most immune escape.

Experiments with synthetic viral proteins make it possible to predict which mutations, or combinations of mutations, are most important to monitor.

T.C.: You previously emphasized that "we need to know how well the Delta variant has now adapted to us." What is the situation?

S.A.: With twice the contagiousness of the initial strains, the Delta variant is undoubtedly well-suited to our species in the short term. In the long term, it's less certain: it will depend on the duration of our immunity to infection and the costs associated with immune escape for the virus. We know that certain mutations allow the virus to escape the antibodies of recovered patients or vaccinated individuals, but we don't know how contagious these mutated viruses are.

M.T.S.: It is important to bear in mind that the concept of adaptation, particularly in the case of an emerging viral disease, is relative: the adaptive landscape mentioned earlier is actually driven by movements comparable to ocean swells. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2 illustrates well the image of the "arms race" we are engaged in with it: for the moment, despite ourselves, we have selected more contagious and virulent phenotypes (Alpha and Delta variants). Now, attention is turning to variants that are likely to bypass our second protective filter, which is immunity (post-vaccination and post-infection).

T.C.: Where could a new variant come from?

M.T.S.: A variant appears randomly, just like any other mutant. Each of the nearly 30,000 bases (letters) in the SARS-CoV-2 genome mutates on average every 300,000 division cycles, and an infection can produce several billion viral particles. Ultimately, the vast majority of infected individuals can transmit viruses that are different from those that infected them. It is estimated that, on average, along a chain of transmission, two mutations randomly attach themselves to the SARS-CoV-2 genome each month.

A particular mutant is considered a variant if it exhibits notable changes in one or more characteristics of interest (contagiousness, virulence, immune escape, symptomatology, or resistance to antivirals). The emergence of a variant often corresponds to a mutation surge, with evolutionary rates 2 to 4 times higher.

Ultimately, every infection that is not prevented is an opportunity for the virus to mutate and potentially generate a variant. Fortunately, these events remain very rare, as the majority of mutations are deleterious.

It is the population in which the virus circulates that determines which mutations will be advantageous in that particular context (we say that selection pressures differ): if this population is not immune at all, the most contagious strains are favored; if it is immune, then the strains capable of evading this immunity spread more widely.

S.A.: To this, we can add the case of chronic infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. In this case, the level of "intra-patient" selection is added to the level of population selection. However, it has been shown that during an infection lasting several months, the immune system selects SARS-CoV-2 viruses with mutations that have been found in variants.

In theory, this outcome is not automatic and, for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) for example, it is believed that intra-patient adaptation occurs at the expense of spread within the population. In any case, this result means that the co-circulation of HIV and SARS-CoV-2 in unvaccinated populations such as those in sub-Saharan Africa is a major health issue, as already reported during the evolution of the Gamma variant.

T.C.: What can we say more specifically about the origin of Omicron?

S.A.: The new Omicron variant was identified in South Africa, but it did not necessarily originate there. The country detected it thanks to the quality of its epidemiological and genomic monitoring. In this regard, the international community's reaction of rejection towards this country is problematic, as it risks discouraging surveillance efforts.

While the exact origin of this variant is currently unknown, it most likely comes from a region of Africa where monitoring of the epidemic is limited. In fact, there are virtually no recent SARS-CoV-2 virus sequences similar to that of Omicron: genome analyses indicate that its common ancestor with other variants dates back to mid-2020! This means that it may have originated from strains that have been circulating for over a year without being sampled (which is highly possible given the low level of investment in monitoring the epidemic in many African countries).

It is also possible that the virus passed through an animal reservoir, as some of its mutations are intriguing. We know that SARS-CoV-2 can infect mammals and, in some cases, such as on mink farms, there have been instances of it returning to the human population. However, for Omicron, there is still very little data available to explore this hypothesis.

T.C.: The term "evolutionary leap" has been used for certain variants. What does that mean?

S.A.: This touches on an old debate in evolutionary biology between proponents of "gradualism," which can be traced back to Charles Darwin, and those of "punctuated equilibrium" (leaps), popularized by Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould. The truth lies somewhere between the two, and the current pandemic offers a good example of this.

We know that SARS-CoV-2 naturally accumulates genetic mutations at a fairly steady rate, which is what allows us to track it in phylodynamic studies. But the evolution of variants also results in widespread changes in the genome, or "selective sweeps" where a beneficial mutation (and associated sequences) becomes fixed: first with the D614G mutation (at the very beginning of the pandemic, the614th amino acid of the Spike protein was usually aspartic acid— "D" in the specialized nomenclature; here it is replaced by a glycine, "G," editor's note), then with the Alpha variant (the Beta and Gamma variants remained in the minority worldwide), and then the Delta variant.

So depending on the scale you look at (month or year) and the criteria you use (neutral mutations or so-called phenotypic mutations affecting biological properties such as contagiousness), you will see either continuity or jumps.

T.C.: And how should we interpret Omicron, which has 53 mutations, including around 30 on the spike protein alone?

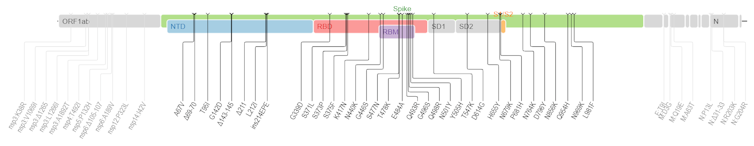

S.A.: At the moment, we know very little about Omicron, but its mutation profile is indeed intriguing. As analyzed by South African viral evolution expert Darren Martin and his colleagues, these mutations can be classified into three groups:

- On the one hand, there are all the mutations and deletions surrounding the N501Y mutation in the Spike protein (Δ69-70, K417N, N501Y, H655Y, P681H). The latter has already been described as profoundly altering the adaptive landscape of the virus, i.e., the range of its possibilities.

- Secondly, still in the Spike protein, there is a second set of mutations at positions that have already mutated in other variants, for example at position 484 (N440S, S477I, or E484A). These are expected to have an effect on the phenotype of infections, such as their contagiousness, virulence, or ability to evade the immune response.

- Finally, there is a set of 14 mutations that are very rare in circulating lineages and virtually absent from other known sarbecoviruses (a subgenus of betacoronaviruses that includes coronaviruses linked to severe acute respiratory syndrome, including SARS-CoV-2, editor's note). Furthermore, individually, these mutations appear to be counter-selected. Their presence is therefore currently a mystery, as the variant seems well adapted to our species. One possibility is that there is a collective effect of these mutations or an interaction with other mutations (such as N501Y) according to a phenomenon of epistasis, common in population genetics: even if two mutations A and B are deleterious in isolation, their joint presence may be advantageous.

It should be noted that two sub-lineages of Omicron have already been identified. They are designated BA.1 and BA.2, and do not both have the same key mutations.

Mullen J, Tsueng G, et al., and tCfVS/https://covdb.stanford.edu/page/mutation-viewer/#omicron/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

T.C.: What other signs would be cause for concern, apart from these mutations?

M.T.S.: The most striking point is that Omicron is associated with a very strong resurgence of the epidemic in South Africa, just after the Delta variant wave. On this point, it should be noted that it is very difficult to understand national contexts. For example, our team is working hard to understand the epidemic in France. Therefore, to assess the severity of the epidemic situation in a country, it is best to rely on that country's epidemiologists and health agencies... And in the case of South Africa, these specialists are concerned.

Several experiments involving exposing the virus to antibodies from vaccinated or recovered individuals are currently underway. None have been published yet, so it is difficult to draw conclusions, especially since the preliminary results vary considerably between studies—and even within certain studies.

It should be borne in mind that these experiments indicate a general trend and do not capture the diversity of the immune response. Ultimately, statistical analyses of epidemiological studies will be the most useful. In this regard, an initial field study suggests that the virus is capable of causing more reinfections than other strains. In other words, Omicron's rapid growth could be explained more by its ability to circumvent immune responses than by its R₀.

T.C.: How widespread is Omicron really on a global scale?

S.A.: Omicron has already been detected in dozens of countries, including France. This distribution is reminiscent of what is known as a "source-sink" dynamic in ecological science: we would have a region of the world where this virus is predominant and a phenomenon of dispersion underway.

In several countries that are monitoring their epidemics closely, notably the United Kingdom and Denmark, we are already seeing a very rapid increase in tests consistent with this variant. Indeed, as it has a deletion at positions 69-70 of the Spike protein, one of the screening tests that has three targets in the genome returns positive results with two of the three targets present.

M.T.S.: In France, screening data, which involves searching for specific mutations, provides an almost real-time picture of the spread of a group of genotypes. The advantage is that this technique is less expensive and faster than full genome sequencing. However, only the latter can identify the variant with certainty.

T.C.: Do we have any idea how many variants (of interest or concern) may have emerged without being detected?

S.A.: All eyes are obviously on the new Omicron variant right now, but it's hard to say how many mutants of interest exist globally. It's quite likely that several have emerged without subsequently breaking through. Even with a selective advantage, the early stages of a variant's spread are governed by chance.

M.T.S.: In a simplified model, the probability of an epidemic dying out is 1/R₀. As a first approximation, with an R₀ of 3, in 33% of cases the chains of transmission die out spontaneously. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 may have been introduced into France on several occasions, and the quest to identify an index case is questionable.

This is also why it is possible that there have been several outbreaks of variants whose chains of transmission have died out on their own. Indeed, super-spreader events (due to gatherings without protective measures, etc.) play a key role in the spread of this virus, with the majority of transmissions occurring in a minority of cases.

T.C.: What are the other variants currently being monitored most closely?

S.A.: In France, we are closely monitoring the B.1.640 lineage, which was first detected in March 2021, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo. It is not listed as a variant of interest by the WHO, but it appears to be spreading quite rapidly. Our team has also identified the circulation of Delta variants carrying at least two mutations associated with immune escape in the spike protein (T95I and E484Q). For the moment, their circulation remains limited.

In any case, the emergence of the Omicron variant reminds us of the need for a long-term vision to emerge from this pandemic. Apart from the scientific advisory board, few are concerned about this, as it contradicts the immediacy of politics and the media. While it is just one player among many, scientific research has an important role to play, from developing treatments to anticipating viral evolution.

Unfortunately, it is a long-term process, which makes it unattractive to politicians... and it suffers from a lack of scientific knowledge that is widespread throughout almost all sectors of French society. With the recent elimination of biology and physics-chemistry classes for the majority of high school students, belief in miracle solutions is likely to worsen.![]()

Samuel Alizon, Director of Research the CNRS, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Mircea T. Sofonea, Senior Lecturer in Epidemiology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases, MIVEGEC Laboratory, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.