[LUM#13] Plastic pandemic, a step backwards

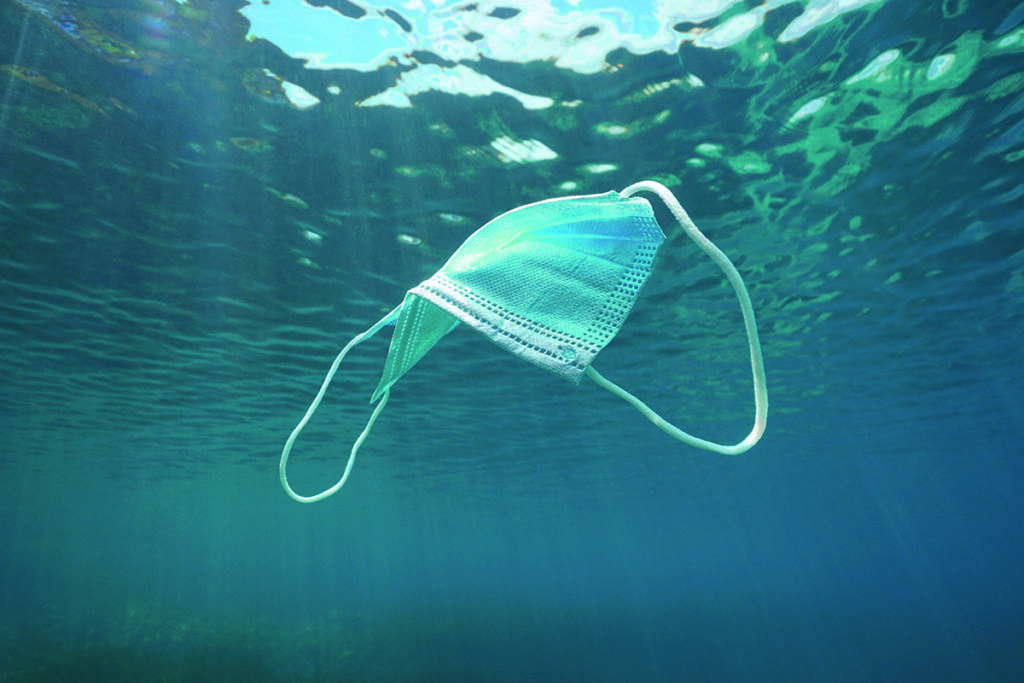

The timid wave of "deplasticization" that began a few years ago has been overwhelmed by another wave: the Covid-19 pandemic. Plastic is making a strong comeback in the midst of the health crisis, causing an alarming rebound in the flow of all kinds of synthetic polymer waste.

It is one of the unfortunate side effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: the big comeback of plastic. Everywhere. In fast-food restaurants and cafeterias, where reusable cups and glasses have been replaced by disposable ones. In stores, where plastic bags are making a strong comeback at the checkout. In shops, where protective screens are popping up everywhere. In drive-throughs and their over-packaged groceries. In the thousands of bottles of hand sanitizer that are all the rage. And above all, on our faces, covered with those famous disposable masks made of polypropylene microfiber, the plastic resin par excellence.

Detoxification

Why has the health crisis brought the tentative move away from plastic that had been underway to a halt? "Fear is the main driver behind this sudden craze for all-plastic products, " explains Nathalie Gontard, a researcher at the Agropolymers Engineering and Emerging Technologies Laboratory*. Fear? Fear of being infected with coronavirus. "Because it is disposable, plastic appears safer to people, establishing itself as the hygienic material that saves lives by preventing contamination due to reuse."

However, this reputation is undeserved. "The virus can survive for several hours to several days on all surfaces," explains Valérie Guillard*. "A coronavirus can even survive much longer on plastic than on glass or metal. It also remains longer on a disposable polypropylene microfiber gown than on a cotton gown or paper surface," adds the polymer specialist.

Even disposable masks may not be as essential as we think: "Masks made from natural fibers such as cotton, flannel, silk, or hemp have filtering capabilities that are just as effective as surgical masks made from synthetic fibers. They trap at least 80% of particles with an average size of 60 nanometers thanks to a combination of physical filtration and electrostatic effects," explains Nathalie Gontard. According to experts, the performance of a mask, regardless of the type of fibers used, provided they are sufficiently dense, is mainly related to how well it fits the contours of the face.

Economic issues

Plastic isn't so fantastic. And yet this illusion of health safety represents an incredible opportunity for manufacturers in the sector, who have rushed to fill the gap without hesitation. "The economic stakes are such that some manufacturers are not hesitating to ride the wave of anxiety linked to the health crisis to defy the bans and revive their businesses, " laments Nathalie Gontard. On April 8, theEuPC, the lobby group for European plastics converters, asked the European Commission to postpone the European directive adopted in 2019 that bans the marketing of several single-use plastic products. "Fortunately, this request was rejected."

And yet the plastic boom is already clearly visible. This is evidenced by the increase in waste to be processed, which has been particularly noticeable in Spain since the start of the epidemic. This poses a real risk not only to the environment but also to health, as the researchers explain: "Plastic persists in our environment for up to several centuries in the form of micro- and then nanoparticles: plastic microfibers break down, fragment, multiply, spread throughout our environment, become loaded with pollutants, and ultimately contaminate our food chain and threaten the proper functioning of the organs of all living beings."

The cure worse than the disease

The microfibers in our masks are therefore likely to end up on our plates or those of our grandchildren. "These disposable synthetic polymer masks should carry a warning label saying 'seriously harmful to the health of our grandchildren, '" says Nathalie Gontard. "Washing a natural fiber mask remains the most effective form of recycling for eliminating the virus, as well as being the most economical and least harmful to the environment," adds Valérie Guillard.

And when it comes to COVID-19, the rampant use of plastic masks could well indirectly fuel the epidemic... How? "Numerous studies point to the fact that the transmission of the virus could be linked to fine particle pollution in the air, which comes in part from the degradation of plastic films and fibers, and therefore polypropylene masks," explains the specialist, who denounces a remedy that is likely to become worse than the disease.

For both researchers, it is urgent to "de-plasticize" our lifestyles. "Plastic should only be used in areas where it is essential. Wherever there are plastic-free alternatives, we must adopt them. This would allow us to limit our use of plastic to the bare minimum, " advises Valérie Guillard. Adopting alternatives, but also simply limiting our consumption. "There are many items—often made of plastic—that we could easily do without," adds Nathalie Gontard. " For many of us, lockdown has been an opportunity to reflect on our lifestyles and values. We can hope that this questioning will leave a lasting impression on everyone..." This will calm our enthusiasm for plastic objects and prevent them from leaving indelible marks on the environment.

See also:

Find UM podcasts now available on your favorite platform (Spotify, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, etc.).

* IATE (UM, INRAE, CIRAD, Institut Agro-Montpellier SupAgro)