Planning for better care: the example of myocardial infarction

According to the World Health Organization, 17 million people die each year from heart attacks and strokes.

Jérôme Azé, University of Montpellier; Jessica Pinaire, University of Montpellier; Paul Landais, University of Montpellier and Sandra Bringay, University of Montpellier

The institution emphasizes that deaths from cardiovascular disease account for approximately 31% of all deaths worldwide, making it the leading cause of mortality. The burden of these diseases is expected to increase to 11.06% by 2030, bringing the number of cases to around 36.2 million. Cardiovascular diseases are a major public health issue, placing a heavy burden on the sector's resources.

In this context, combating modifiable risk factors (smoking, sedentary lifestyle, overweight or obesity, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol or triglyceride levels, etc.) is obviously essential. But there is also another important avenue to explore: improving health planning, i.e., all measures that improve the efficiency of the healthcare system.

Demonstration using the characterization of patient flows hospitalized for myocardial infarction in France.

See also:

Cardiovascular risk factors, a revolutionary discovery that is not so old

Inequalities with serious consequences

Health planning aims to ensure the efficiency of the healthcare system, but also to reduce inequalities and geographical disparities in access to care.

These inequalities begin with regional disparities in healthcare provision, with the most significant disparities relating to the distribution of specialist doctors. For example, the Île-de-France and PACA regions have high concentrations of doctors, whereas these are much lower in northern and central France. Healthcare provision is particularly limited and very unevenly distributed in rural areas. In addition, 20 to 30% of hospital doctor positions are vacant, and 30% of general practitioners are over 60 years old and cannot find replacements.

These inequalities can havesignificant consequences on health: because of them, one-third of French people who live far from health services forego care. The greater the distance to travel to receive treatment, the greater the decline in the frequency of consultations, as well as the refusal to undergo certain tests. Difficulties are also encountered in cases of emergency hospitalization (childbirth, myocardial infarction, stroke, trauma, etc.).

Tracing care pathways to improve planning

Inequalities also affect mortality risk. For example, France is the European country with the highest differences in the risk of death before age 65 between people in manual and non-manual occupations.

An effective way to help improve this planning is to gain a better understanding of the patient's care history: what care they have received, how many times, etc. Considered as indicators of patients' real needs, these "care pathways" also provide information on treatment times and costs. We sought to better understand these trajectories in the context of hospitalization for heart conditions.

The originality of our approach lies in having studied the national medical-economic databases generated by the Medical Information System Program (PMSI). The PMSI is managed by the Technical Agency for Information on Hospitalization. This public institution, which reports to the Ministry of Health, is a center of expertise in the four "fields" of hospital activity: medicine, surgery, obstetrics, and dentistry; follow-up care or rehabilitation; psychiatry; and home hospitalization.

In France, each hospitalization results in the production of a summary of the stay. This document describes the patient's main and associated diagnoses, certain characteristics of the stay (admission/discharge method, duration, etc.), as well as the procedures performed. This medical and administrative data is recorded in the PMSI databases. These databases are not intended for use in medical applications, but are valuable for healthcare planning.

Making information visible

In this era of digitization of healthcare systems, many researchers are interested in data mining methods. These methods have already proven their effectiveness in the healthcare sector, whether in identifying underdiagnosed patients, reducing healthcare system costs, or detecting insurance fraud.

One challenge associated with using this data is successfully designing tools that can both process such a large amount of data and extract relevant information from it.

In the case that concerns us, myocardial infarction, we extracted spatio-temporal patterns characterizing care trajectories in order to better describe and understand patient flows. Specifically, using an artificial intelligence technique, we identified sets of individuals in the data who had experienced similar medical events over time.

The originality of the method lies in matching patients based on the similarity of the pathologies recorded in the PMSI databases. For example, if one patient is admitted for an acute transmural myocardial infarction of the inferior wall, and another is admitted for an acute transmural myocardial infarction of the anterior wall, they will be considered to have experienced a "similar" medical event, as both diagnoses belong to the same subgroup of the disease "acute myocardial infarction."

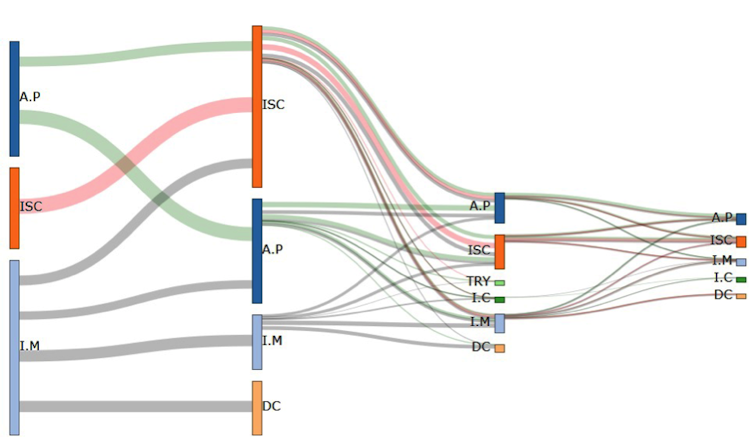

The patterns identified were then integrated into a visualization tool. This makes it possible to reconstruct the various possible developments of a disease. Here is an example of the flow of patients over the age of 65 hospitalized for cardiovascular disorders.

DR, Author provided

We were thus able to identify three streams, whose initial events are angina pectoris, ischemic heart disease, and myocardial infarction, respectively. These streams then split into several branches, whose subsequent events are those already mentioned, plus death. From the third hospitalization onwards, two new events appear: cardiac arrhythmia and heart failure. We also note that patient flows decrease over time (some of the patients having died since the initial flow).

This type of visualization allows three key stages in patient flow patterns to be identified: myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and ischemic heart disease.

The majority of patients show signs of recurrent coronary insufficiency in the form of angina pectoris. Many of them also suffer another heart attack and/or develop ischemic heart disease. Others are affected by conditions such as aneurysm, ischemia, rhythm or conduction disorders, or heart failure. In addition, data indicate that 21% of men and 32% of women hospitalized die, most often during their first hospitalization.

These results are consistent with some of the possible developments of myocardial infarction.

A powerful forecasting tool

In addition, we grouped these care pathways to identify trends in the time between hospital stays and changes in rates. Combining these time and rate profiles provides a basis for developing new strategies for organizing care.

At the institutional level, these trajectories are valuable for planning beds and staffing. At the national level, this method allows for a territorial analysis. Indeed, previous studies have highlighted a North-South gradient not only for hospitalizations or readmissions, but also for mortality related to myocardial infarction. Exploring patient flows by incorporating the parameter of the patient's region of origin would make it possible to compare care and disease progression while taking this context into account.

Finally, the results obtained from these flow analyses can now be integrated into a decision support tool for clinicians. This will enable them to tailor their recommendations and warn their patients about potential risks by comparing their profile with that of patients who have undergone similar treatment pathways.![]()

Jérôme Azé, University Professor, University of Montpellier; Jessica Pinaire, Research Engineer, University of Montpellier; Paul Landais, University of Montpellier and Sandra Bringay, University Professor, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.