Chemical pollution and the cocktail effect: a path toward toxicological testing without animal experimentation

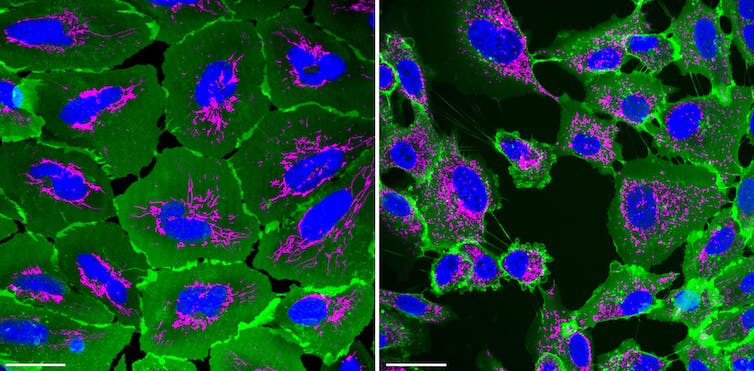

Here is an image showing mitochondria in pink: these are the lungs and "powerhouses" that enable cells (in green, with their nuclei in blue) to breathe, live, and perform their functions.

Abdel Aouacheria, University of Montpellier

In healthy cells on the left, mitochondria are relatively long and interconnected, resembling a road network seen from above; whereas in stressed and damaged cells on the right, their network is fragmented into a constellation of solitary mitochondria, which produce less energy and will eventually precipitate the cells into suicide.

Mitochondria are therefore a good barometer of the health of our cells, with the architecture of their networks even varying in tissue from sick individuals. Thanks to real-timeconfocal imaging, using high-content imaging robots in particular, we can reveal in less than a second the contours of a living cell, its nucleus, and unique "organelles" (the elements of a cell that perform specific functions, such as mitochondria), in order to study the effects of different pollutants on cells and their health.

Rapid imaging of mitochondria as an "early warning system" for environmental health

Air, water, and food contamination, soil pollution, noise pollution: measuring the impact of environmental risks on the health of organisms and ecosystems is no easy task.

The images generated by imaging platforms are processed by computers to provide valuable information about the effects of the many pollutants that surround us.

This is a step forward in deciphering the "exposome," a concept introduced by British scientist Christopher Paul Wild in 2005 and defined as the totality of exposures to which an individual is subjected throughout their life (from conception to death).

Indeed, external pollution (air, water, soil) and internal pollution (home, office, car) not only have negative effects on our health (triggering chronic diseases) and that of ecosystems (which are experiencing an unprecedented decline in biodiversity and agricultural yields), but also entail enormous socioeconomic costs.

One in six deaths each year is attributed to it, which is three times more than AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria combined. We are also constantly exposed to a "chemosphere" (a mixture of substances) whose risks are poorly understood: epidemiologists and toxicologists have only been able to assess the toxicity of a tiny fraction of the 350,000 chemicals registered since the 1960s in the main national and regional chemical inventories (for production and commercial use).

The health and environmental impact of these compounds, which may jeopardize the integrity of the Earth system, remains poorly characterized when studied separately. What's more, their potential "cocktail effects" (the effects resulting from exposure to several substances at the same time, which are sometimes more harmful than "single" exposure) are almost never tested due to a lack of ad hoc technologies.

How can we translate the reality of these multiple exposures at the cellular level of an organism?

A new generation of toxicology tests without animal experimentation

This is where mitochondria come into play. Fragmentation of mitochondria and the mitochondrial network is an early indicator of their loss of functionality and therefore a marker of environmental danger.

The principle of the method consists of staining (with vital dyes) the mitochondria and other components of cells cultured in vitro. These cells are primary human cells, or cell lines, from various tissue sources (e.g., skin, lung, kidney, intestine) that are exposed to toxic substances found in our environment, such as pesticides or fine particles. There is no need to sacrifice an animal for each experiment.

Using software, a set of parameters is calculated from confocal microscopy images: the size of mitochondria, their circularity, and their degree of connectivity are among the hundred or so possible descriptors that can be used to highlight the harmful effects of toxic substances, either alone or in combination (cocktail effect).

The objective is to link initiating molecular events, such as exposure to these chemicals, with harmfulness or toxicity at different biological scales, from cells and tissues to organs and individuals. While mitochondria connect toxicities and alterations expressed at the microscopic level (cells) with adverse effects and pathologies observed at the tissue level, uncertainty remains regarding the extrapolation of toxicological data obtained in vitro to possible effects on organisms and ecosystems.

Ultimately, this system could also make it possible to identify ingredients capable of protecting or restoring the "mitochondriomes" (all of the mitochondria) of cells exposed to pollutants.

Abdel Aouacheria, Biologist, Research Fellow at the CNRS, specialist in cell life and death, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.