Why are there so few women in French research?

Gender equality in research and innovation is one of the key principles of the European project.

Julie Mendret, University of Montpellier and Martine Lumbreras, University of Lorraine

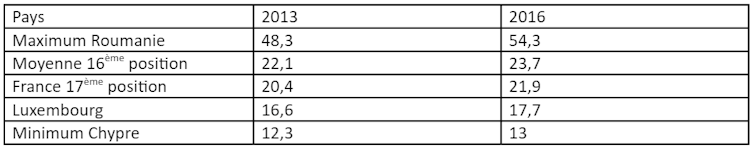

This is a crucial challenge because, although women aged 25 to 34 in the European Union are more likely to have a higher education degree than men, the proportion of men working as scientists or engineers far exceeds that of women.

In many European Union countries, female researchers are significantly underrepresented, with the Netherlands at the bottom of the table (25% in 2016) and Romania leading the way with 46%. France, with 28% of female researchers, is below the European average of 33%. Within the European Union, as in France, only 20% of researchers in companies are women, with a higher representation in Spain (31%).

She Figures 2018, Author provided

Under these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that barely one in seven patents is filed by a woman. Despite the positive upward trend in the participation of female inventors in the international patent system compared to their male counterparts, the situation is still far from balanced. The proportion of women using the patent system remains low compared to the number of scientific articles they publish each year, a phenomenon known as the "leaky pipeline." Based on current rates of progress, gender parity in the field of patents will not be achieved until 2070.

Still not enough female science students

While girls and boys perform similarly in science subjects in high school, young girls gradually drift away from science subjects as they progress through their studies. In France, in 2017, 55% of higher education students were women. In the 16 years since 2001, their numbers have increased in engineering schools (+4.9 points) and in university health programs (+6.8 points). However, they remain in the minority in the most selective programs (42.8% in preparatory classes for the grandes écoles) and, above all, in science-related fields (37%). In 2017, 10,600 of the 38,000 engineering graduates were women, representing 28%. This is an increase of 32% in 10 years, but progress remains slow.

Among female science students, the choice of specialization remains highly gendered: in 2017, 61% of women studied life sciences, compared with 28% who studied fundamental sciences. This gendered specialization in education continues in the workplace. In 2015, in the field of mathematics and software design, 14% of researchers in companies were women. In the field of medical sciences, they represent 61% of the research workforce.

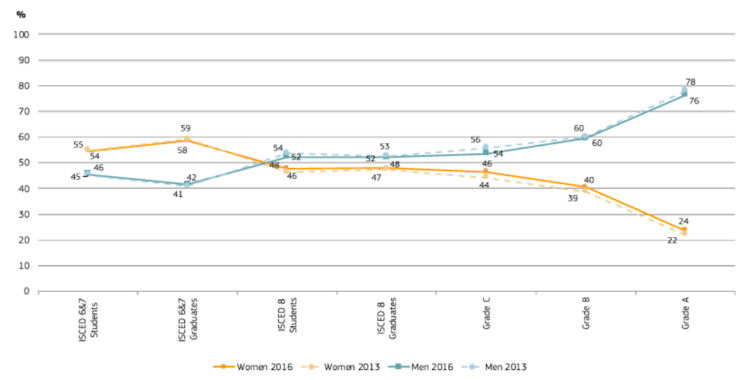

Another observation is that, after graduation, women's employment conditions are systematically less favorable (employment rate, stability, salary, etc.) than those of men. The glass ceiling is still very much present within the European Union, particularly in academia. It refers to all the obstacles women face in accessing senior positions: it is as if an invisible ceiling prevents women from climbing the ladder. Thus, during an academic career, for example, gender inequalities continue to widen.

She Figures 2018, Author provided

France is not setting an example in Europe.

The case of French academia is telling: there are not enough women in French universities (37%) and their progression to professorial positions is low (25% of female researchers in universities). However, the recruitment of Professors to become more female-oriented, but women are less likely to apply for positions. Gender parity in management bodies has improved thanks to legislative and regulatory measures that require it, in particular the ESR law of July 22, 2013, which enshrines gender parity in all governance bodies. Despite this, women remain very much in the minority in the highest positions. Barely 17% of universities were headed by women in 2019.

This trend could be linked to the weight of tradition: women must take care of their families and daily life. As a result, some give up on having greater ambitions, daunted by the amount of work required to achieve them. For example, the need to travel both within France and abroad for collaborations or participation in international conferences in order to raise their level of research can pose serious problems if the researcher does not have "flexible" childcare assistance.

Towards a new, freer generation

However, the younger generations are gradually freeing themselves from this burden. What's more, those who overcome this obstacle achieve excellent results. The pursuit of excellence in the public sector by women (who represent 39% of researchers in the public sector) is now widely recognized, with public research organizations awarding 42% of the highest distinctions to women in recent years.

The goal of the Ministry of Higher Education, Research Innovation is to achieve 40% female representation in scientific fields by the start of the 2020 academic year. To achieve this, it is relying in particular on initiatives such as those proposed by our association Femmes & Sciences, which aims to encourage young girls to pursue scientific and technical careers and to strengthen the position of women in these professions.

Among the measures implemented is a mentoring program for women scientists designed to support female doctoral students in building their careers. This program is based in particular on the formation of pairs: a mentor supports a student mentee. The pairs are formed by affinity during a speed-meeting, ensuring that the mentor and mentee do not belong to the same entity.

Discussions may focus on the mentee's career goals, questions, difficulties encountered, or any other topic she wishes to address based on her needs. Our pioneering group in Montpellier F&S launched the mentoring program in 2015, with the support of a doctoral school (15 pairs).

Since then, the program has grown in scope and is now supported by the University of Montpellier, the CNRS, and, as of this year, an agricultural engineering school. The field of discipline is expanding, as is the number of volunteers (both women and men) wishing to become mentors. This mentoring has already proven useful in difficult situations (such as harassment), where the mentor has been able to help, together with the university authorities, to ease tensions.

In France, public authorities and industry have taken note of the imbalance in the number of female scientists. The gap is gradually closing, but unfortunately very slowly, and we are still lagging behind other European countries. Testimonials in schools, industry-sponsored events (Girl's Day), competitions, and initiatives such as mentoring are aimed at closing the existing gap.![]()

Julie Mendret, Senior Lecturer, HDR, University of Montpellier and Martine Lumbreras, Professor Emeritus, University of Lorraine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.