When marine biology meets robotics

To study marine fauna in the Indian Ocean, the BUBOT project is putting big data to work for biology. The project involves robotizing underwater observations and then developing the algorithms needed to study the thousands of hours of video footage collected. This project is supported by I-SITE MUSE as part of its 2018 research support program.

Why use robots when diving is part of the charm of discovering underwater life? For marine biologists, robotization holds great promise for unprecedented observations, as it allows marine habitats to be explored for hours on end at depths of over 20 meters. Through new observation tools, the BUBOT (Better Understanding Biodiversity changes thanks to new Observation Tools) project is opening a new window on marine biodiversity in the Indian Ocean.

Low-cost robot

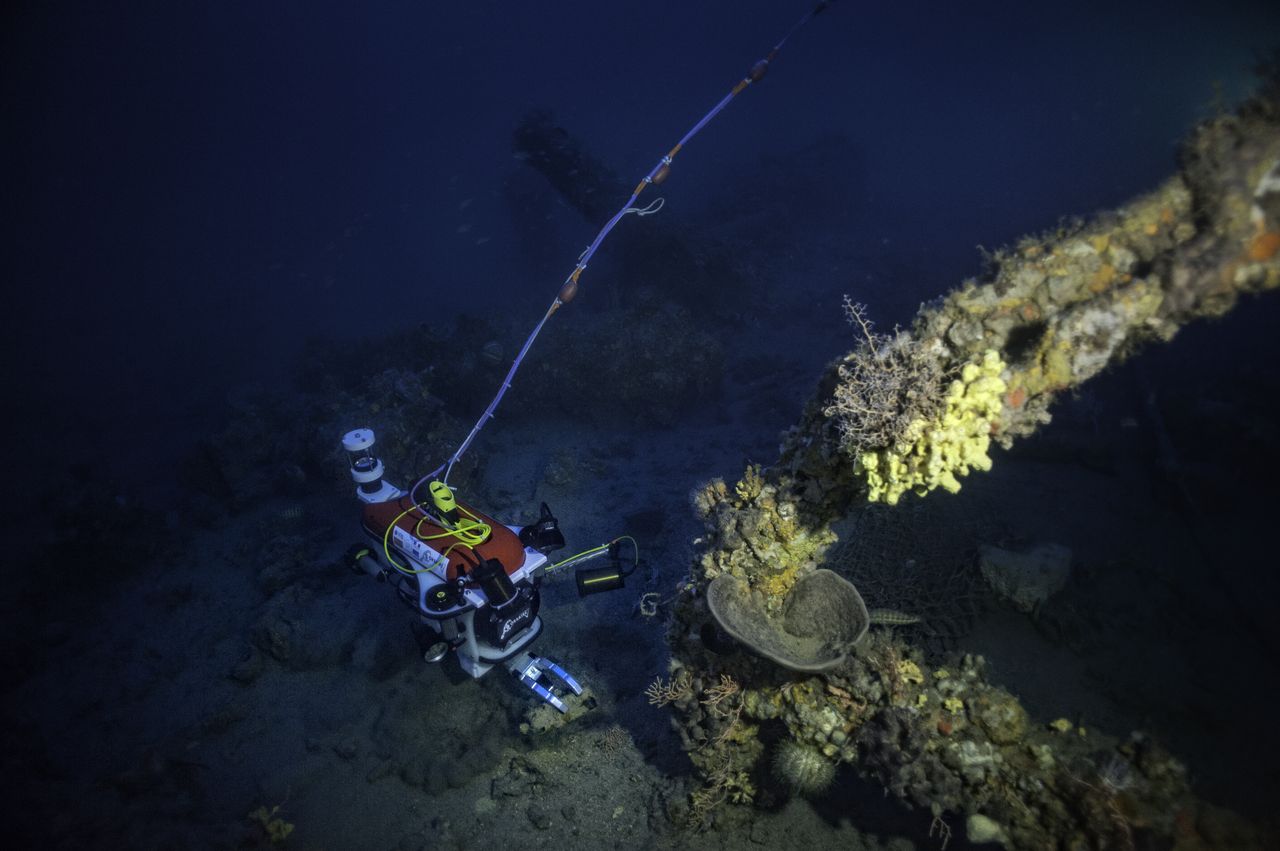

The first step is to create a robot that will automate observations at depths of ten to one hundred meters, enabling the study of coral reef biodiversity across this vertical gradient. "Biologists gave us precise specifications for creating the ad hocrobot," explains Karen Godary-Déjean of LIRMM (Laboratory of Computer Science, Robotics, and Microelectronics of Montpellier). Specifically, the robot must be able to perform a transect autonomously, avoiding turtles, nets, and other drifting objects. Equipped with sensors, the device will therefore have to navigate around obstacles, slow down, and turn around. Another constraint is the price, because although the underwater technology exists, the cutting-edge versions available are prohibitively expensive, costing hundreds of thousands of euros.

"Video surveillance of the sea"

Robots are not the ultimate solution. Cameras placed on the seabed are a complementary tool for observing the seabed over a long period of time. "It's like video surveillance of the sea," says Camille Magneville, a PhD student at the Marbec (Marine Biodiversity, Exploitation and Conservation) laboratory, as she describes the system she installed at two sites in Mayotte, one in a protected area and the other in a fishing zone. With twelve cameras, she collected nearly 500 hours of video in four days, which will provide a better understanding of the diversity and ecological roles of fish at each site.

However, big data is only useful for research if it can be used to exploit the masses of data produced by automated systems. BUBOT therefore includes a section on artificial intelligence: teaching machines to recognize fish species in order to automatically analyze all the images recorded by cameras, whether they are mounted on a robot or fixed. "Thanks to all the videos collected in Mayotte, we hope to be able to recognize more than 100 species within two years (which should represent more than 95% of the individuals visible in the videos)," explains Sébastien Villéger, a functional ecology researcher at MARBEC. To train the deep learning algorithms, the project is receiving help from students, mainly from the University of Montpellier, who are putting their taxonomy skills into practice to annotate the fish in the videos. "Our goal is to have a wide variety of postures, conditions (light, apparent color), and backgrounds for each species, so that the algorithm is ultimately effective in all situations," the researcher points out.

In addition to identifying species, assessing the size of each individual is also a crucial aspect of studying underwater ecosystems. This measurement is not currently possible with the GoPro cameras mounted on the robot. The next step, therefore, is to equip the robot with a video system featuring stereo cameras.

Talkative fishermen

Transdisciplinarity being a must, BUBOT also draws on the humanities to understand the environment through the knowledge of the first observers, the fishermen. A geographer and an anthropologist complete the team. In Mayotte, they conducted nearly thirty interviews and reported on the scarcity of fish in certain areas, the displacement of fishing grounds, and other useful information for choosing study sites. And artisanal fishermen are talkative. "The interviews last a little over three hours on average, and the fishermen are happy to share information about their fishing grounds," says Esmeralda Longépée of UMR Espace-Dev.

Due to Covid, BUBOT has fallen slightly behind schedule. Another unexpected change to the program is that, of the three areas initially covered by the project, the fieldwork in Mozambique has had to be canceled, as the country has recently been classified as a dangerous zone. It will be replaced by the Comoros. As for the first site, the Scattered Islands, the initial underwater expeditions have proved promising, with a wealth of biodiversity. However, given the difficult diving conditions on a steep drop-off, the team is eager to send its robot there.