What role does culture play in municipal elections?

Once again this year, it seemed as though nothing was going to happen. Debates between political and apolitical municipal candidates once again appeared to avoid any reference to culture, continuing the trend seen in previous elections, including the last presidential elections.

Emmanuel Négrier, University of Montpellier

At the time, the National Federation of Local Authorities for Culture (FNCC) criticized a "soft" consensus on culture, which was rarely criticized but rarely the subject of innovative projects. To understand why we may be changing our position, we need to examine the particular moment we are facing. Let's review the reasons for not talking about culture during a campaign, then those for bringing it up in the 2020 campaign.

The notable absence

There are three reasons why most politicians have little to say about culture during election campaigns. The first is that it is not a divisive issue for the population, unlike traffic congestion, urban planning, or the commercial desertification of city centers. It is not divisive because it relates to a positive vision of politics, which is often credited to the outgoing elected official. We are a long way from the 1970s and 1980s, when the new urban middle class expressed its frustration by demanding a cultural policy that did not really exist at the time. Apart from a few rare examples, the opposition has little interest in focusing the debate on what is positively identified with city life.

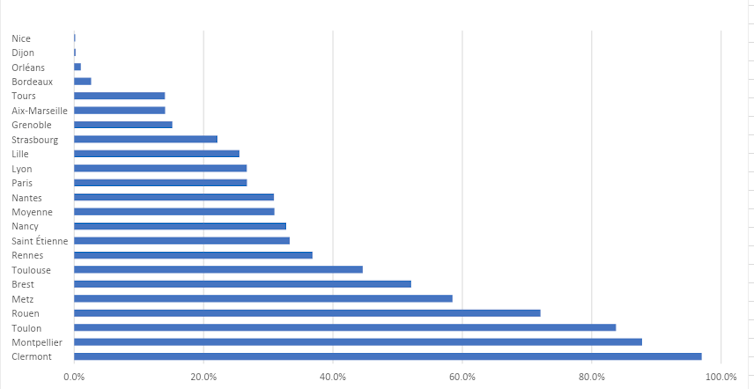

The second reason is that it is extremely difficult to envisage any scope for planning other cultural initiatives. Admittedly, there is the possibility of transferring responsibility for cultural management from the municipal level to the inter-municipal level. The following diagram shows that, except in a few cases, city centers continue to exercise most of the responsibilities in this area.

Author's analysis based on data from DEPS/Ministry of Culture, Author provided

Cultural metropolises are as bold in words as they are timid in deeds. One reason for this is that the undeniable success of cities' cultural facilities and events goes hand in hand with a growing deficit in organizations. This is a very old economic law, known as Baumol's law: contrary to the theory of economies of scale (the bigger it is, the less it costs relatively), in the performing arts, the more the activity grows, the more it costs, even when, as a "victim of its own success," the same concert is repeated twice. However, in most local authorities today, the focus is more on saving than on investing in sectors that, more than others, depend on public subsidies.

The third reason is the impression shared by many elected officials (except perhaps those in the field of culture) that public cultural policy has largely fulfilled its promise: to complete the catalog of facilities and labels, the list of which has been broadly proposed by the Department of Culture since the 1970s. Already in the 1990s, Bernard Latarjet noted that France had an effective, if not complete, cultural network. Culture would therefore no longer be a subject of debate, since the fight for it had finally secured its rightful place. It was time to move on to other things.

Breaking away from the weak consensus

However, two factors challenging this "soft consensus" have emerged during the term of office that is coming to an end. On the public policy side, recent years have seen a real discourse of revitalization of cultural policies, supported in particular by recent laws (Law No. 2015-991 of August 7, 2015 on the new territorial organization of the Republic; Law No. 2016-925 of July 7, 2016 on freedom of creation, architecture, and heritage), recognizing, for example, the concept of cultural rights.

The catalog of cultural policies has been enriched with new objects and totems. These are often based on a desire to break down barriers between culture, territory, education, environment, etc., and no longer just between culture, economy, and society. This is particularly true of cultural projects in rural or peri-urban areas, which generally do not have the means for professional specialization, and where the purpose of cultural action is combined—often successfully—with objectives of economic development or residential attractiveness. This is also true in the case of joint actions between health policies and artistic intervention, which are studied in more detail by Chloé Langeard, Françoise Liot, and Sarah Montero.

This de-sectorization can be interpreted as a sign of the weakening of culture (its value in itself) in the spectrum of public policy. But it may also hold promise for renewal around new uses and values of art in society.

On the political spectrum, the novelty of these elections lies in particular in the possibility of victory for far-right candidates, skillfully molded into the local populist mold. The second is the emergence of citizen lists calling for a municipalist overhaul of the local agenda. The first of these two forces is virtually silent on this issue today. The Front National lists, with their euphemistic tactics, only mention the beautification of streets and the care taken to preserve heritage in order to fuel their cultural difference, which has become relative in the invocation of the program (in action, it is quite another matter).

At the other end of the spectrum, however, new criticisms of this epic municipal cultural policy are beginning to emerge. Questions are being raised about grandiose, expensive, and time-limited events, such as those organized by the Royal de Luxe company in Nantes and Toulouse.

In the speeches of the Green Party, in the statements of municipalist and participatory lists—such as "Nous Sommes" in Montpellier, for example—we see the emergence of criticism of an elitist metropolitan influence, which has allegedly been detrimental to a culture of proximity, service, and social or popular access:

"We want a city that promotes amateur artistic and cultural practices, the work of artists, collective projects led by residents and associations [...] We reject a two-tiered, elitist culture. We reject the overfunding of an inaccessible, capitalist culture."

A new era for culture

What can be said about these criticisms? First, they are paradoxical: any survey of attendance at so-called "radiating" facilities (regional municipal libraries, national opera houses and orchestras, national drama centers, etc.) shows how dominant the surrounding audience is. The discourse of influence—which would be logical given the multi-level funding structure of these institutions—is countered by a fairly high degree of localization of audiences. This is a general phenomenon. For example, major festivals (lasting more than four days, with more than 70,000 spectators and more than 50 concerts), which are the epitome of influence, have long shown a gap between their internationalized line-up and their regionalized audiences. Regional artists account for less than a third of the line-up, while regional and local audiences account for nearly two-thirds of the audience.

But above all, despite their vagueness, these criticisms are a sign of a new era for culture. While cultural policies have not yet reached their final destination, they have nevertheless completed a phase of their existence marked by a "neo-Keynesian" approach to supply: facilities were made available in areas where there was no demand. This discrepancy, the result of productive investment, was gradually absorbed by demand that responded to the call of supply. This is how, for example, a circus audience was formed in Toulouse, an opera audience in Lyon, a dance audience in Montpellier, and more generally, the rise of cultural and artistic scenes specific to a city or metropolis, as shown by Charles Ambrosino and Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux.

This phase had multiple effects, including the creation of professional cultural environments in cities, counties, and regions. But today, demand is tending to break free from the gentle constraints of supply. Where are the artistic developments happening today? Notably in cooperatives, fab labs, and cultural third places whose vocations are artistic, economic, civic, and political.

The causes championed are social, urban, environmental, and cultural. What is their place in the public cultural policy agenda? Marginal, often negotiated at the crossroads of cultural, economic, social, and neighborhood budgets. Between this cultural emergence and the major institutions of artistic excellence and certification, the inequality is striking and exchanges are weak. It is precisely here that a renewed debate on municipal cultural policies will take place. Should we maintain unequal and separate treatment of excellence and emergence? What bridges can be built between the two? How can we connect the aspiration for greater proximity to cultural action with the positive otherness without which cultural policy becomes stale?

This – still tentative – emancipation of demand from the dictates of supply is good news. In a field as vague as culture, public action cannot be satisfied with a stable and unique perimeter or paradigm. It must constantly reinvent its boundaries and the multiple meanings given to it, in a democracy, by citizens of equal dignity.![]()

Emmanuel Négrier, CNRS Research Director in Political Science at CEPEL, University of Montpellier, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.