Resurgence of the Covid epidemic: why the Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 variants are spreading in France

Forgotten by the media for several weeks, the Covid epidemic is back in the news with the BA.4 and BA.5 variants taking hold in France, after their breakthrough in Portugal in particular.

Samuel Alizon, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Mircea T. Sofonea, University of Montpellier

Specialists in epidemiology and the evolution of infectious diseases within the "Infectious Diseases and Vectors: Ecology, Genetics, Evolution, and Control" unit (University of Montpellier, CNRS, IRD), Mircea Sofonea, associate professor, and Samuel Alizon, research director, analyze the situation in France. What can be said about these variants? Will they lead to a new wave this summer?

The Conversation: The Omicron variant, which has become the dominant strain worldwide, continues to spread and evolve. But its new variants are now designated BA.1, BA.2, then BA.4 and BA.5... How can we keep track of them all?

Samuel Alizon: Indeed, it's easy to get lost in this proliferation of nomenclatures! Greek letters were introduced by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2021 with the Alpha variant. This is probably the worst classification system, as it was developed without taking evolutionary biology into account. The Pango and Nextclade classifications are much more appropriate. In fact, the WHO seems to have stopped updating its classification system and now groups all BA-type variants under the generic term Omicron.

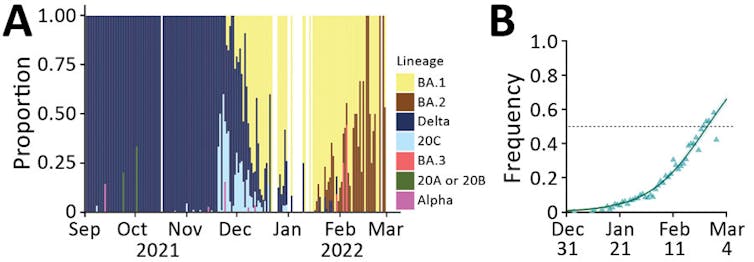

Sofonea et al. (2022, Emerging Infectious Diseases)

We modeled the circulation of variant lineages in France in a recent study (see above), and the first Omicron wave caused by the BA.1 lineage emerged at the end of 2021. This was quickly supplanted by the BA.2 lineage, which caused a second wave of hospitalizations in April 2022. Now the BA.4 and BA.5 lineages are taking over.

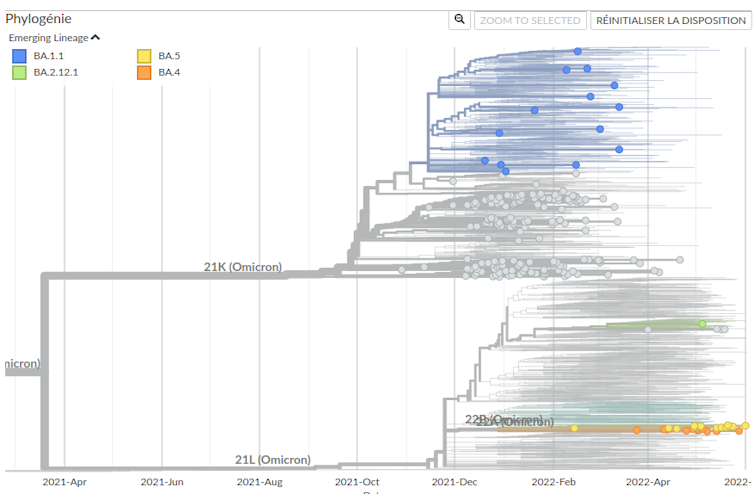

Mircea T. Sofonea: These lineages were identified in May, but they likely emerged in December 2021 in South Africa, potentially from BA.2, the dominant lineage in France since March 2022.

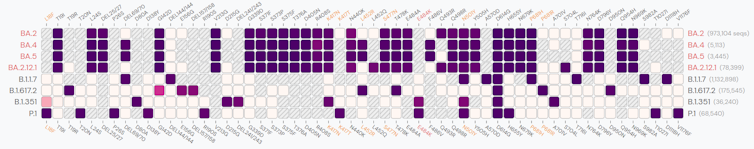

While the BA.2 variant was as different from BA.1 as the Delta variant was from the Alpha variant, the evolutionary divergence between BA.4 and BA.5 is more limited.

However, even though the number of new mutations is limited, some are cause for concern. For example, the 452R mutation in the spike protein is known to confer greater affinity with the human ACE2 receptor, which the virus uses to enter our cells. The 486V mutation, also in the spike protein, gives the virus a fairly high capacity for immune evasion.

Nevertheless, caution should be exercised when applying analogical reasoning to isolated mutations. This is because the effect of these mutations is neither absolute nor cumulative; it depends on the entire genotype, with potential synergistic and antagonistic phenomena, including for distant positions on the genome (known as epistasis).

TC: Are these mutations innovations of these variants, or are BA.4 and BA.5 "drawing" from all the possibilities that have been tested by their predecessors—Delta, Gamma, Beta, Alpha?

MTS: Remember that Omicron is not a descendant of previous variants, but a distant cousin, and that viruses do not mutate voluntarily or in a controlled manner. The mutations detected in the genome of a new lineage appeared by chance.

The 452R mutation was not present in the BA.1 or BA.2 lineages, but it was found in the Delta variant. It is also one of the three mutations sought in the screening tests currently carried out on all positive PCR tests in France.

The 486V mutation is not associated with any of the strains circulating within our species, but experiments known as deep mutational scanning, which involve generating proteins with mutations, had identified it as potentially involved in immune evasion.

SA: Regarding the differences between variants, two genetic mechanisms are involved: mutations and recombination. The latter allows entire portions of the genome to be mixed when two viruses from different lineages "co-infect" the same host.

At the biological level, several hypotheses coexist to explain the emergence of variants: increased circulation in a population, the involvement of an animal reservoir, or chronic infections in immunocompromised individuals. Indeed, the latter are unable to eliminate the virus, which therefore causes longer and more lethal infections. A preprint (to be treated with caution, as it has not yet been peer-reviewed) by a team in New York describes the intra-patient evolution of a BA.1 virus with the accumulation of key mutations and, most importantly, its transmission to at least five other people.

In the case of BA.4 or BA.5, as their differences from BA.2 are fairly limited, they may simply be mutations that have become established as the virus has circulated.

TC: Why are BA.4 and BA.5 spreading in France now?

SA: It is easy to estimate the growth advantage of one lineage over another in a population. According to our team, BA.5 has a growth advantage of around 9% over BA.2 in France.

However, it is difficult to know where this advantage comes from. Is BA.5 spreading more because it is more contagious? Or is it because it is better at evading immunity? A preprint by a Japanese team and a publication by a Chinese team highlight the role of immune escape, particularly via the 486V mutation.

Regardless of the origin of this advantage, it may contribute to an epidemic rebound in France.

MTS: A second mechanism is also at work in France: SARS-CoV-2 immunity—which is essentially hybrid, i.e., both post-vaccination and post-infection—declines over time since the last immunogenic event (whether infection or vaccination).

While the protection conferred by an Omicron infection or athird dose of vaccine remains significant after five months against severe disease, it is greatly reduced against infection in general. The population's susceptibility to the virus (i.e., the counterpart to herd immunity) therefore rebuilds over time, ultimately opening up the possibility of a resurgence of the epidemic.

In summary, BA.4 and BA.5 are spreading as our immunity wanes, and are doing so more rapidly than BA.2 because they have the dual advantage of contagiousness and immune escape. BA.4 and BA.5 are therefore causing an earlier wave than BA.2 would have done.

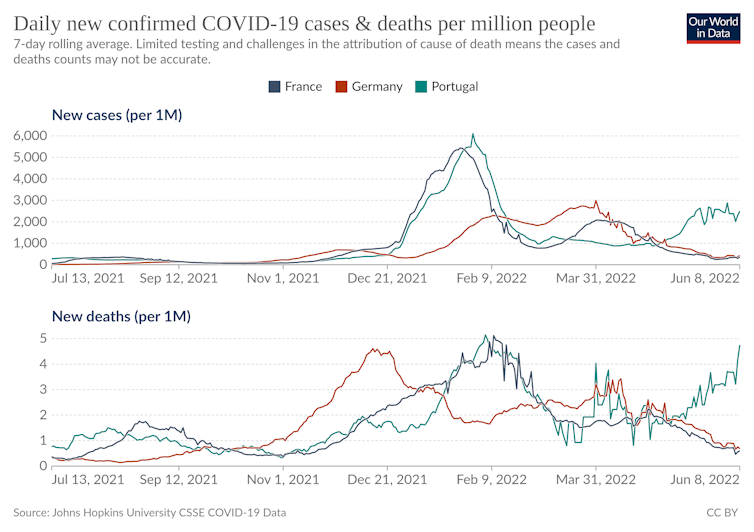

TC: The situation in Portugal may have been cause for concern. But can we learn anything from the trends observed in other countries?

MTS: I am cautious about comparisons between countries: they are becoming increasingly difficult, because current circulation depends not only on the health measures in place, but also on epidemiological and immunological history, which varies increasingly from country to country.

In France, it is still difficult to quantitatively compare the easing of measures contributing to the recovery with the summer context that limits it, with longer and warmer days encouraging social interactions in open spaces.

SA: Portugal is one of the European countries where the BA.4/BA.5 wave is most advanced and is accompanied by an increase in hospitalizations. It is difficult to know why it started so early there, but, as with all outbreaks, random events such as "superspreading" probably played a major role.

Globally, in South Africa, the BA.4/BA.5 wave appears to be on the decline. In the United States, however, BA.2 was initially replaced by the BA.2.12 lineage, but this now appears to be being replaced by BA.5.

TC: Can we anticipate the consequences of these replacements between variants on future epidemic peaks?

SA: In 2021, in France, a new variant replaced the old ones because it was more contagious. Since December 2021, immune escape has been leading the way.

This makes scenario modeling difficult. The models developed by our team, as well as those developed bythe Pasteur Institute and the Pierre Louis Institute of Epidemiology and Public Health, already took into account vaccination coverage in the population and the percentage of people who had been naturally infected.

On the other hand, including the time elapsed since the last vaccination or natural infection is a challenge because, after two years of pandemic, two vaccination campaigns, and a huge BA.1 wave, everyone now has different immunity!

MTS: We have developed tools to take into account this heterogeneity of immunity in populations. Given our constraints, we are currently focusing on the long term, but in theory it should be possible to use this framework to explore short-term prospective scenarios.

At this point, it is difficult to say exactly how widespread the new wave of the epidemic will be. This wave, in genetic or virological terms, is already well underway, and BA.5 will likely become the dominant strain by June 20. While we can count on the summer to reduce the incidence compared to winter, it will not, on its own, prevent a wave of infection. For the record, one of the peaks in circulation in France remains August 2020, and the fourth wave, which began in September 2021, was even higher than the previous one.e wave (from Delta) peaked in July 2021.![]()

Samuel Alizon, Director of Research the CNRS, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Mircea T. Sofonea, Senior Lecturer in Epidemiology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases, MIVEGEC Laboratory, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.