[LUM#18] Beneath the oceans, the Earth

What if the secrets of Earth's formation lay beneath the sea? Last May, geologist Benoît Ildefonse took part in the Arc-en-Sub campaign organized by the French oceanographic fleet. Their destination was Rainbow, an underwater dome formed on the Atlantic Ridge, whose dynamics still elude researchers.

"In marine geology, we work on the oceans but without the water, because what interests us is what lies beneath." And to once again explore "what lies beneath," Benoît Ildefonse took part in the Arc-en-Sub campaign last May.He spent 26 days at sea aboard the Pourquoi pas ?, one of four ships in the French oceanographic fleet. "There were about 20 scientists on board: geophysicists, petrologists, people interested in rocks, others earthquakes, but all geologists," says the director of Géoscience Montpellier, who has lost count of the number of sea campaigns he has carried out since the very first one in 1997.

And for this mission, we set course for the Rainbow Massif, an underwater dome rising to 1,500 meters below sea level, located on the Atlantic Ridge two days' sail west of the Azores. "What we call ocean ridges are essentially volcanic mountain ranges 60,000 kilometers long, located between approximately 1,000 and 4,000 meters deep, which correspond to the boundaries of tectonic plates , " explains the geologist. These plates can collide or drift apart at speeds ranging from one centimeter per year for the slowest, such as the Atlantic Ridge, to fifteen centimeters per year for the fastest, in the eastern Pacific.

A crust factory

True factories for manufacturing the Earth's crust thanks to the magma escaping from their faults, ridges are also areas of intense hydrothermal activity. "Cold ocean water slips into the faults and, upon contact with the magma, heats up to several hundred degrees, "continues Benoît Ildefonse. When this water, which has picked up a number of chemical elements along the way, reaches supercritical conditions, it rises and emerges in the form of plumes. These plumes, when they come into contact with colder seawater with a different chemical composition, precipitate minerals such as manganese and iron sulfides."

In addition to the unique biodiversity they harbor and the precious minerals they contain, these ridges play a vital role in cooling the planet. "It is estimated that the entire volume of the ocean is recycled in this circulation more than 100 times in 80 million years. In one day, this represents more than 1 million Olympic swimming pools or 45 Salagou lakes."

Although the Rainbow site has been known for 25 years, scientists have not yet fully understood how it works, hence this latest mission. "The topography of the site corresponds more to that of a volcanically inactive area, yet we are seeing hydrothermal activity that implies the presence of pockets of magma below, but we don't know exactly where they are,"summarizes the researcher. Another factoris that scientists have discovered an older, lower-temperature site with different rocks near this high-temperature site. "This indicates geographical and temporal variability in this system, and this campaign aimed to explore this complexity."

Change of scale

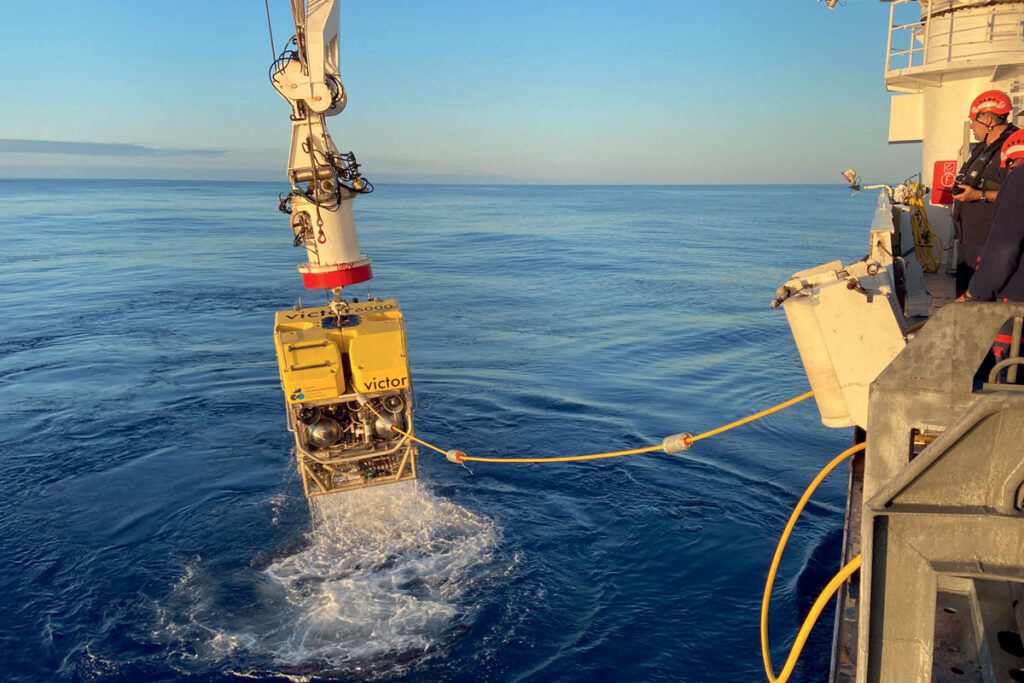

To achieve this, geologists collected more than 320 rock samples from the depths of the sea and filmed nearly 200 hours of video footage. Victor, a remotely operated submarine, and IdefX, an autonomous underwater vehicle, were also used to produce a micro-bathymetric map of the area on a scale of a few centimeters, as well as systematic photographic coverage of the seabed. "This detailed mapping has revealed some extraordinary things. The analysis of the data and samples will now enable us to place all this in a comprehensive integrated framework combining magmatism, hydrothermalism, and tectonics," says Benoît Ildefonse.

Since returning from their mission, the scientists have been analyzing the samples in their own specialized fields: chemical composition and variability, mineralogical changes linked to reactions with hydrothermal fluids, etc. The Montpellier geologist is interested in their deformation, measuring the orientation of crystals using an electron microscope and 30-micron-thick slides. "These microstructures provide information about the temperature at which these rocks were deformed," explains Benoît Ildefonse, before concluding: "In geology, we very often work on a very small scale to understand dynamics that operate on a very large scale."

At sea with the FOF

" The French Oceanographic Fleet (FOF) is a tool I know well," explains Benoît Ildefonse, director of Géoscience Montpellier. " In the French scientific landscape, it is what we call a very large research infrastructure, like the Soleil synchrotron or certain telescopes." In 2000, he boarded the Atalante for the first time, one of the FOF's four ocean-going vessels operating under the direction ofIfremer, the CNRS, theIRD, and the network of French marine universities, to which the University of Montpellier belongs. For the past four years, Benoît Ildefonse has chaired the FOF's National Offshore Fleet Commission and, in this capacity, participates in the selection and evaluation of the various campaigns carried out. " I love being at sea. I like the routine that sets in, working in shifts, especially the 4/8 (4 a.m.-8 a.m./4 p.m.-8 p.m.) because you get to see the sunrises and sunsets. Sea campaigns are always extraordinary human adventures."

Find UM podcasts now available on your favorite platform (Spotify, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, etc.).