[LUM#13] Spike, the spy working for screening

What if the solution to the ever-growing queues outside testing centers could be summed up in one word: SPIKE? Five letters that sound like a code name for a specific protein in the virus that could form the basis of a new, faster, and more effective test for detecting SARS-CoV-2. and more effective.

PCR or serological test? Nasopharyngeal, blood, or saliva sample? Since the beginning of the epidemic, testing has become part of our lives, bringing with it a host of questions: waiting times, reliability, discomfort, etc. "The tests used today are not optimal. We are working on new solutions that would not only increase testing capacity but also improve their sensitivity and specificity," explains Christophe Hirtz, a researcher at the Laboratory of Biochemistry and Clinical Proteomics*.

Spike, a specific protein

Unlike PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) tests, which seek to detect the presence of the virus genome, blood or saliva tests known as "Elisa" tests can detect specific proteins found in large quantities on the virus envelope. "One of these, which we call the Spike protein, is of particular interest to us because it has a sequence specific to the virus and is crucial for its entry into the cell. If we find this sequence, we know we are dealing with SARS-CoV-2. There is no mistaking it," the researcher continues.

To detect this spike protein, Christophe Hirtz and his team use mass spectrometry. This analytical tool allows molecules to be located and identified by their mass and their chemical structure to be characterized. "Mass spectrometry will enable us to characterize the protein, but also to understand the antigenicity of the virus, in other words how our immune system will recognize the virus and trigger the right antibodies."

Identifying Spike using antibodies

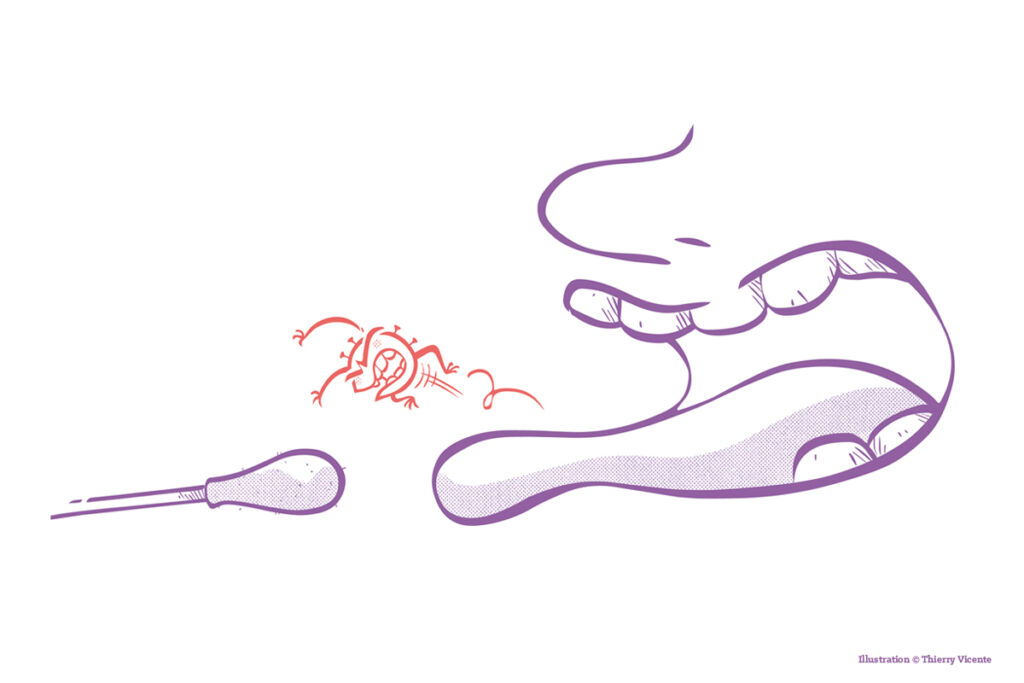

When a virus enters our body, our immune system identifies a characteristic protein, in this case Spike, and triggers the production of specific antibodies capable of capturing this protein. "An antibody and a protein work a bit like a key and a lock. If we identify the antibody capable of capturing the Spike protein, we can use it to detect the presence of the virus and thus establish an even more reliable and rapid diagnosis."

Although seemingly simple, this task is nonetheless challenging because many "decorative" elements present on the spike protein, such as sugars, can influence how the antibody targets it, forcing researchers to expand their characterization work. "Our molecular analysis must be extremely detailed and take into account the different environments of the spike protein in different samples taken from different types of patients, whether in intensive care or not, asymptomatic or not," the researcher continues.

To collect these samples, the Clinical Proteomics Platform was able to count on the collaboration of the CHU's biological resource center, which has been storing patient samples since the beginning of the epidemic, as well as the virology library atthe Pasteur Institute in Lille, a partner in the study. "We are increasing the number of sources and samples in order to obtain applicable results; otherwise, we remain in the realm of basic science," says Christophe Hirtz. "Our goal is really to develop an optimized diagnostic test."

Understanding the diversity of symptoms

A diagnostic test and perhaps even more, as analyzing the spike protein in different environments could also provide a better understanding of the diversity of symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2. "We are going to compare samples from patients who have reported an extremely virulent form of COVID-19 with others who have developed a milder form and see if there are any small differences in this spike protein that could explain the diversity of cases we are observing."

Scheduled to last 18 months, this project led by Sylvain Lehmann, head of the LBPC, should quickly yield initial results, enabling researchers to establish the profile of the antibody capable of targeting the Spike protein. From there, there are two possibilities: "either the antibody already exists on the market, as there are a multitude of synthetic antibodies available, and the test will be relatively simple to develop, or it does not exist and will need to be produced. " For this final phase, researchers at the Clinical Proteomics Platform have secured the collaboration of Montpellier-based company IdVet, another partner in the project, "but it will not be the same price or the same time frame. It takes about six months to produce a purified antibody," concludes the researcher.

Find UM podcasts now available on your favorite platform (Spotify, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, etc.).

*LBPC (UM, Inserm, Montpellier University Hospital)