Is stimulating the brain to improve performance really effective?

Fatigue, in the common sense, is a feeling of physical or cognitive weakness, and manifests itself as difficulty in continuing an effort. The physical limits of human performance have been the subject of study for a considerable time.

Stéphane Perrey, University of Montpellier

Starting in the 1890s, two works by Dr. Fernand Lagrange and Dr. Angelo Mosso marked the beginning of the study of muscle fatigue during exercise in humans. Most research during the20th century focused on the locomotor muscles, lungs, and heart, all considered to be major organic determinants in the etiology of fatigue and therefore exercise performance.

The role of the brain in fatigue

For many years, much of the literature ignored the importance of the brain in regulating physical performance. However, at the beginning ofthe 20th century, muscle fatigue was suggested to be a physiological process associated with a sensation involving the brain as a decision-making organ, a kind of regulator that protects the body from any catastrophic disorder caused by exercise that depletes its physiological reserves. We can see that this "catastrophe" approach, proposed more than a century ago, is in line with the most contemporary approaches to muscle fatigue (the "flush" model or psychophysiological model) debated through the central governor model.

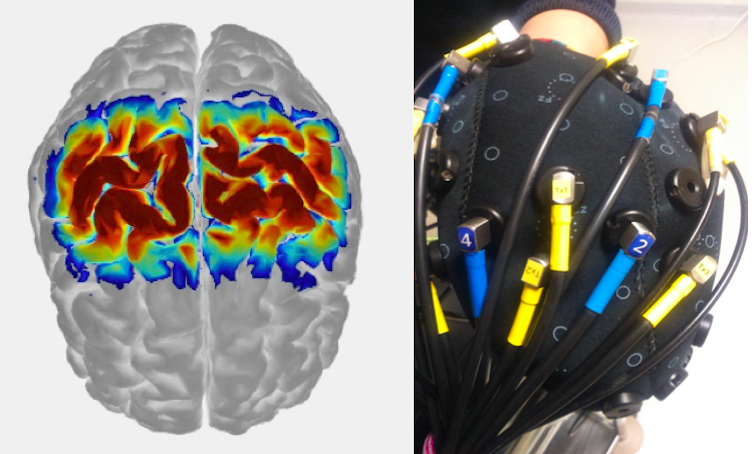

With the introduction and development of new non-invasive devices (neuroimaging and brain stimulation equipment), knowledge about brain behavior during exercise has advanced. A first step was taken with studies using neuroimaging methods that identify different areas of the brain that are active during muscle exercise.

Author provided

In addition, over the past decade, a non-invasive technique of brain stimulation using low-level electrical current (1-2 mA) applied via electrodes has been the focus of intense research in the quest to modify the functioning of our brains. Reading scientific publications, one might be tempted to believe that applying transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) to different areas of the brain can enhance physical performance. But is this really the case?

Author provided

Significant lack of evidence of the effects of brain stimulation on performance

The number of experimental studies on the effect of tDCS on physical performance is growing rapidly, but there are significant methodological limitations to consider. To date, the number of studies remains limited, and the physiological mechanisms by which tDCS could improve physical performance are still partly unknown. The potential improvement in physical performance identified in a few studies appears to result from greater transient activation of cortical neurons after a short sequence of 10 to 20 minutes of tDCS.

However, few studies have measured brain activity after and during (online effects) a sequence of tDCS coupled with exercise. Second, the spread of the electric field induced in the brain by tDCS is very diffuse. Thirdly, the vast majority of studies are based on very small samples, which could increase the likelihood of false positive results, as is often the case in neuroscience. Finally, the absence of a blind procedure may have led to a number of unwanted confounding psychological effects, which may have played a significant role in the excessive variability of the results observed.

Stimulating the brain to boost performance: moving toward neurodoping?

Some authors have already argued that tDCS can be considered a new form of doping, although skepticism about the validity and reproducibility of tDCS effects has also been expressed. tDCS can potentially improve athletic performance in two ways: either by modulating brain activation just before a sporting event, or by reorganizing cerebral cortex activity after multiple applications (hypothesis of greater neural efficiency). As discussed in the previous section, recent meta-analyses take a very cautious stance on the acute effects of tDCS on performance, and no studies have yet been conducted on the effects of chronic tDCS administration on physical performance.

Despite recent experimental research into the potential of tDCS to improve physical performance, its application has rapidly evolved outside of laboratories. Several tDCS devices are now available to the public, and many athletes and teams, both professional and amateur, claim to have adopted tDCS as part of their training programs.

In the field of sports doping, brain stimulation was already being experimented with by Soviet athletes in the 1970s. Although still in its experimental stages, tDCS appears to satisfy only one criterion defined by the World Anti-Doping Agency, namely the potential to improve athletic performance. It remains to be determined whether this represents a violation of the spirit of sport and whether tDCS poses a real or potential risk to the health of athletes. Although no serious adverse side effects have been reported in healthy participants, there are many uncertainties regarding the prolonged use of tDCS. Determining whether or not an athlete has used a tDCS protocol before a competition is impossible and could open up an unprecedented scenario for anti-doping control strategies.

More concerning from an ethical and regulatory standpoint, the "do-it-yourself" concept has rapidly grown, with online forums and social media offering kits and instructions on how to build tDCS devices for the purpose of enhancing cognitive or physical abilities.

These devices are not approved by official bodies such as the Food and Drug Administration. Attempts to stimulate the brain with homemade electrical devices are not new and have been known since the late 19th centuryEven though tDCS is not considered a means of improving physical performance due to a lack of convincing evidence, it could add a marginal gain, which could be enough to provide a high-level advantage. Regardless of the potential of tDCS, its use must be based on rigorous evidence and not serve commercial purposes or be promoted through media hype based on anecdotal evidence.![]()

Stéphane Perrey, University Professor, Deputy Director of the EuroMov Laboratory, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.